The Grand Ole Opry (34 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

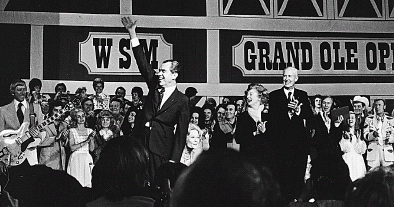

President Nixon waves to the Opry audience.

HAL DURHAM:

You’ve probably seen those pictures of President Nixon playing piano, and all the Opry people backstage, but when I look at

that photo I see many non-Opry people with no connection to the show who somehow got into the group. The first show ran forty-five

minutes late. It was a cold night in March, and the second-show crowd was waiting outside to come in. We finally just ran

the show straight through, emptied the house, and let the second-show crowd come in without actually having an intermission.

The show ended that night about an hour and twenty minutes late.

Among those performing the first show at the new Opry House were Sam McGee, who, with his brother, Kirk, first performed on

the Opry in 1926.

SAM M

C

GEE:

There’s people here now, I tell ’em how it was back in the early days, and they don’t even believe me. There’s only seven

or eight of us original members left now. We had no idea when we started that [the Opry] would make such a go of it. I felt

for a while that when our music was over, when we were gone, why that’d be the end of it. But it seems lately that people

are getting interested in our music again. This Opry House is fine. It’s the finest thing that could happen to the Opry. It’s

a place to show off. You can’t sell barbecue without setting it out and saying, “That’s barbecue, folks.”

Among those returning to the Opry in the months after the move was DeFord Bailey. On the occasion of his seventy-fifth birthday

in December 1974, he was brought onstage by Roy Acuff, who had worked with him in the late 1930s.

The move to Opryland was more than justified by the increased attendance. In 1974, the Opry drew 482,178 people; in 1975,

attendance reached 751,546. The cost for National Life had been more than anticipated, but WSM president Irving Waugh reasoned

that the Opry was still a benefit to National Life in its battle with bigger insurers.

The move had been exhausting, but once the Opry was installed in its new premises, the question remained of what to do with

the Ryman Auditorium. Early on, the prevailing opinion was that it should be demolished. National Life brought in a consultant,

Jo Mielziner, who’d staged a production of

Romeo and Juliet

at the Ryman in 1935. Mielziner told the board that the Ryman was “full of bad workmanship and contains nothing of value

as a theater worth restoring. In its latter life as part-time housing for theatrical presentations, there is absolutely not

an item of true value because of the total inadequacy of this structure for this kind of operation.” Only a few benches and

signs should be saved, concluded Mielziner, and perhaps after the Ryman had been torn down, a modern concrete hall could be

built to stage theatrical productions.

Roy Acuff to DeFord Bailey, December 16, 1974: “I guess DeFord traveled with us about six or seven years. I used him whenever

I wanted to draw a crowd. DeFord would play and then I’d go on and try to hold their attention.”

ADA LOUISE HUXTABLE,

the

New York Times,

May 13, 1973:

In the name of reasonableness, the company [National Life] has sponsored studies that have come up with the not surprising

news that preservation is “economically unfeasible.” [But] there was probably no landmark rehabilitation that was not called

economically unfeasible before it was successfully done. The latest study is by Jo Mielziner, who is not the most qualified

expert on old building renovation, to put it mildly. . . . Destroying the Ryman is more than demolishing a touchstone of Nashville’s

past; it means abandonment of a neighborhood that needs help, and speeding the death of downtown. That’s fine for the kind

of redevelopers who wait like vultures to produce sterile new urban pap.

ROY ACUFF:

The Ryman’s going to fall down anyway, so why not tear it down, then people wouldn’t go down to that part of town. The old

Opry house attracts persons who become potential customers for the massage parlors and other adult businesses. It might be

sad to some to tear it down, but I’m not that way. It would be a wonderful idea to take the bricks and build a chapel or church

at Opryland. If they did that, I’d start going back to church. That plan would show the most respect for the building and

Christianity. The Ryman served its purpose and served it well, but if they want to restore it, I’m doubtful anyone could get

it done before it falls down. You can’t heat it. I’ve stood on that stage doing a matinee, and you could see the sky. It’s

a fire hazard and the bricks are falling off the walls. Some crank or fanatic could throw a firebomb in there, and it would

be gone in an hour.

DEL WOOD,

Opry star:

The Ryman is the Carnegie Hall of country music. That’s the problem with this country. Anything old is discarded to make way

for the new. The Ryman is part of our heritage. To keep it doesn’t take anything away from the new Opry House.

SKEETER DAVIS,

Opry star:

I was one of the people who fought, and I will say fought, because we went to the historical boards, people like that to save

the Ryman. Two people who raised their voices to save it were Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. I really didn’t want to go to the new

building in the middle of a park. I still love the old Ryman, and I’m glad we saved it. Neil Young used to be in the wings

of the Ryman when no one knew who he was. Andy Warhol came. I remember sitting there talking to him, and later Roy Acuff asked

me, “Who was that freak?”

At one point, National Life officials proposed using some of the bricks and pews from Ryman to create “The Little Church of

Opryland.” The idea really never made it past this sketch, perhaps in part because of the ridicule from the

New York Times:

“First prize for the pious misuse of a landmark, and a total misunderstanding of the priciples of preservation. Gentlemen,

for shame.”

And so the National Life board deferred a decision on the Ryman Auditorium. It sat empty for years, long enough for downtown

Nashville to be reborn around it.

Ryman public hearing notice, March 12, 1974.

G

RAND

O

LE

O

PRY

NEW MEMBERS: 1980s

B

OXCAR

W

ILLIE

R

OY

C

LARK

J

OHN

C

ONLEE

H

OLLY

D

UNN

P

ATTY

L

OVELESS

M

EL

M

C

D

ANIEL

R

EBA

M

C

E

NTIRE

L

ORRIE

M

ORGAN

R

IDERS

IN

THE

S

KY

J

OHNNY

R

USSELL

R

ICKY

V

AN

S

HELTON

R

ICKY

S

KAGGS

M

ELVIN

S

LOAN

D

ANCERS

B. J. T

HOMAS

R

ANDY

T

RAVIS

T

HE

W

HITES

WHO’S GONNA FILL THEIR SHOES?

H

al Durham managed the Grand Ole Opry from 1974 until 1993. He was the first to allow a full drum kit on the Opry stage, and

he relaxed the number of performances needed to retain membership. But even with the vastly increased attendance at the new

Opry House, Hal Durham and Bud Wendell knew that there was a problem on the near horizon: the show’s stalwarts, Roy Acuff,

Minnie Pearl, Bill Monroe, Ernest Tubb, and Little Jimmy Dickens had joined the Opry in the 1930s and ’40s. Even the lead

announcer, Grant Turner, had been there since 1944. When John Conlee was made an Opry member in 1981, he was the first new

member since Larry Gatlin joined five years earlier.