The Grand Ole Opry (16 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

VINCE HIMES,

Jim Denny’s employee:

Jim Denny ran the concessions. That included soft drinks and hot dogs, which were sold to people waiting in line outside the

Opry for tickets. People started lining up around two or three p.m., and they’d get pretty hungry. The War Memorial and the

Ryman weren’t air-conditioned, so it got very hot in those buildings during the summer. We sold a lot of fans.

Several years would pass before Denny took over the Opry’s Artists Service Bureau. During the war years, he ran the concessions

and opened one of Nashville’s first recording studios so that soldiers stationed in nearby Fort Campbell could record messages

to send home.

During the war, the Grand Ole Opry became more popular than ever. Servicemen from the South were sent across the country and

then around the world, and they took their music with them. The Opry’s homespun music and humor seemed inextricably tied to

the vision of hearth and home that inspired the troops. Ernest Tubb and Roy Acuff became household names during the war years.

Acuff’s searing emotionalism went hand in hand with his music’s spiritual high ground, while Ernest Tubb sang simply and movingly

of loss and separation in songs like “The Soldier’s Last Letter” and “It’s Been So Long, Darling.”

In 1941, several Opry performers were recruited for a Camel road show. The Esty Agency, which handled the Opry sponsor Prince

Albert, organized the Camel Caravan on behalf of R. J. Reynolds’s Camel brand. Until the Opry performers joined the cast,

all of the artists had been pop or jazz since the Camel Caravan’s inception as a radio show in 1932.

MINNIE PEARL:

Someone had the idea of putting the Camel Caravan on the road with three units of the show traveling around the country entertaining

servicemen. They organized a troupe from Hollywood, one from New York, and one from Nashville. Mr. Frank sold the Esty Agency

on using Pee Wee’s show for the Opry Camel Caravan. The young men on the bases came from all over the country, many from places

too far from Nashville for us to perform at because we always had to be back home for the Saturday broadcast. We started in

August 1941. Europe was at war, but the United States wasn’t, and most Americans didn’t think we ever would be. For nineteen

months, we worked three shows a day. In addition to my regular fifty dollars a week from Pee Wee, the Esty Agency offered

me additional fifty dollars if I would act as chaperone to the cigarette girls, who’d walk through the audience passing out

sample packets of Camels.

The Camel Caravan Opry troupe in Florida.

In May 1942, almost six months after the United States entered the Second World War, the government introduced gasoline rationing,

and the draft had already depleted the ranks of sidemen, but Opry stars continued to tour far and wide.

In her newspaper, the

Grinder’s Switch Gazette,

Minnie Pearl described a typical “all-night jump.”

The Camel Caravan touring truck.

Work the Opry ’til midnight—take time out to load up, killing an hour in the process—start out of Nashville saying to ourselves

that we positively will not stop to eat ’til we’ve gone at least seventy-five or onehundred miles. Lots of chatter the first

fifty miles or so, everybody discussing the latest Opry news. Things begin to quiet down. The motor hums, miles slip by, the

driver is wide awake. Into towns and out. Sleepy little towns where sensible folks are asleep like we ought to be. Lights

of an all-night café show up ahead.

Pull over to one side. “Let’s eat.” Sleepy musicians pile out and into the café. “Coffee.” See what’s on the jukebox. “Got

Eddy’s new record. There’s one of Tubb’s. Here’s Roy’s ‘Silver Trumpets.’ Play that one. Better move on, we got miles to go

fellas. Into the car again. Let me sit in the front with the heater. My feet are ice.” Settling down for another forty or

fifty miles. “Hey, wake up, somebody. I can’t take it any longer. I’m dead. My eyes are plumb shut.” “I’ll take it. Wait’ll

I get out and stretch.” “What time is it anyway?” “About 5:30. Almost time for breakfast.” “Not yet, let’s try to make it

to Plainville. It’s only fifty miles from here.” Quiet again. All of a sudden, there’s a bumping sound, not so bad first.

Gets worse. “What’s that?” “Tire.” “Get out, won’t take long.” “That spare okay?” “Fella said he wouldn’t guarantee it.” “Put

it on. May be a filling station down the road.” “Why can’t we have those flats closer to town?” Stop for breakfast. “We ought

to make it in time to clean up a little before the show.” Back in the car again. Lively chatter now. Coffee and breakfast

have waked us all up. “Try that new number. You start it.” Singing for twenty or thirty miles. Best rehearsing in the world,

right there on the road. “Are we on the right road? Haven’t seen a highway sign for miles.” “What’s the time?” “Okay, we’ll

make it if we don’t have any more hard luck. Where do we show tomorrow? We’ve showed there. Good town. Rotten hotel. You remember,

we showed there with the tent show summer before last?” “Let’s get a Coke or something. I’m hungry again.” “Let’s wait and

eat ’til we get there. There’s the town now. There’s one of our showbills. I hope we pack ’em in. Say, where’s the auditorium?”

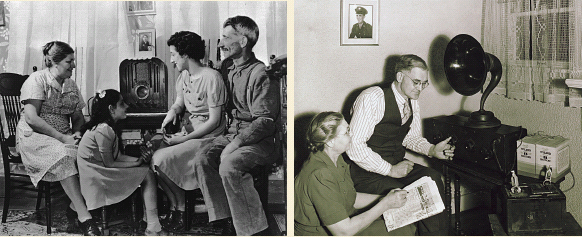

The Camel Caravan’s cigarette girls passed out free smokes and raised morale among the servicemen.

MINNIE PEARL:

Eddy Arnold opened with “I’ll Be Back in a Year, Little Darlin,” and the boys loved it because they thought they’d be home

in a year. Then, after Pearl Harbor, he opened with that song one night and got booed all the way through. The Caravan ended

in 1942. It was too expensive to get us all the way back to Nashville on Saturday night, and travel was becoming more and

more difficult with gasoline rationing and all the rubber for tires going to the war effort.

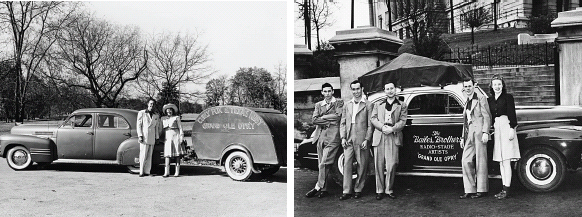

Curly Fox and Texas Ruby (left) and the Bailes Brothers

(right) were among the acts that turned their touring transportation into advertising.

PEE WEE KING:

One time when Minnie was with us, we were traveling back to Nashville. During the war, we were always having flats because

the tires were made of synthetic rubber. We’d already had twelve flats on that trip, and we were hot and tired and frustrated

and late. I was mad as hell. I said “All right, everyone, get out. I’m gonna throw this tire through the windshield.” Minnie

said, “Gus, I do believe Pee Wee is upset.” Gus was my brother-in-law and road manager. He said, “Minnie, I’ve never seen

Pee Wee mad at anything before, but I think you’re right. He’s cussing in Polish.” Minnie said, “I thought he was using cuss

words I’d never heard before.”

Pee Wee King and his fiddle player, Speedy McNatt, ensure that their latest record is on the jukebox.

There have been very few Saturday nights when the Opry wasn’t broadcast over WSM, but one came toward the end of the war.

Report in

MINNIE PEARL’S Grinder’s Switch Gazette:

On Saturday April 14 [1945], the WSM Grand Ole Opry was not on the air. All of the radio stations and all of the networks

observed a three-day period of mourning for our late President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. For those three days, the usual

programs were cancelled, including the OPRY. Announcements were made over WSM to the effect that the OPRY would not be held

that Saturday night. For the benefit of those who had not heard the announcement and had come from a distance to see the OPRY

there was a short musical program at the Opry House for which tickets were not required.

“THE NEWS, THE GRAND OLE OPRY . . . AND THAT WAS IT!”

LORETTA LYNN

in Butcher Holler, Kentucky:

I loved Ernest Tubb even when I was a little girl. I’d lay by the radio on Saturday night with my head right up next to it.

I’d have a coat or something around me. I’d go to sleep crying when he’d sing, “It’s been so long darlin’ since I had a kiss

from you.” It was wartime, you know. During the war, Daddy would say, “We’re gonna save the batteries on the radio.” It was

an old Philco radio. We listened to the news and the Grand Ole Opry, and that was it!

JEAN SHEPARD

in Pauls Valley, Oklahoma:

We listened to the Opry on a sharecropper’s farm in Oklahoma. We saved up and scrimped every year to buy a $2.98 battery for

that radio. My daddy run a ground wire down to this lead pipe in the ground. I’d go out to the cistern and get some water

and pour water around it so we could knock the static out. The Opry would come in loud and clear and it’d be wonderful. Grant

Turner would say, we have cars here from Michigan and Texas and Oklahoma and Ohio, and I’d think, “How in the world did those

people get there?”