The Giza Power Plant (16 page)

Eric went on to say that his company did not have the equipment or

capabilities to produce the boxes in this manner. He said that they would create the boxes in five pieces, ship them to the customer, and bolt them together on site.

F

IGURE

23.

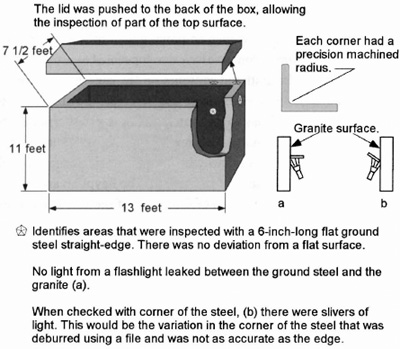

Granite Box in the Rock Tunnels at Saqqara

Another artifact I inspected was a piece of granite that I, quite literally, stumbled across while strolling around the Giza Plateau later that day. I concluded, after doing a preliminary check of this piece, that the ancient pyramid builders had to have used a machine with three axes of movement (X-Y-Z) to guide the tool in three-dimensional space to create it. This artifact is very precise, even though it is a complex, contoured shape. Flat surfaces, having a simple geometry, can justifiably be explained as having been created by simple methods. This piece, though, because of its shape, drives us beyond the question, "What tools were used to cut it?" to a more far-reaching question, "What guided the cutting tool?" To properly address this question and be comfortable with the answer, it is helpful for us to have a working knowledge of contour machining.

Many of the artifacts that modern civilization creates would be impossible to produce using simple handwork. We are surrounded by artifacts that are the result of men and women employing their minds to create tools that overcome physical limitations. We have developed machine tools to create the dies that produce the aesthetic contours on the cars that we drive, the radios we listen to, and the appliances we use. To create the dies to produce these items, a cutting tool has to accurately follow a predetermined contoured path in three dimensions. The development of computer software has allowed some applications to move in three dimensions, while simultaneously using three or more axes of movement. The Egyptian artifact that I was looking at required a minimum of three axes of motion to machine it. When the machine-tool industry was relatively young, techniques were employed where the final shape was finished by hand, using templates as a guide. Today, with the use of precision computer numerical control machines, there is little call for handwork. A little polishing to remove unwanted tool marks may be the only handwork required. To know that an artifact has been produced on such a machine, therefore, one would expect to see a precise surface with indications of tool marks that show the path of the tool. This is what I found on the Giza Plateau, lying out in the open south of the Great Pyramid about one hundred yards east of Khafre's Pyramid (see Figure 24).

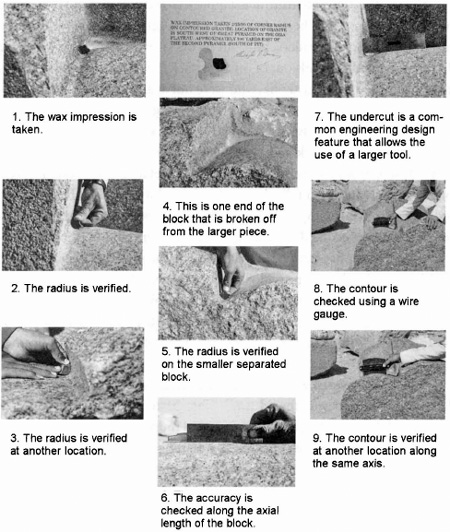

There are so many rocks of all shapes and sizes lying around this area that to the untrained eye these could easily be overlooked. To a trained eye, they may attract some cursory attention and a brief muse. I was fortunate that they both caught my attention and that I had some tools with which to inspect them. There were two pieces lying close together, one larger than the other. They had originally been one piece and had been broken. I found I needed every tool I had brought with me to inspect it. I was most interested in the accuracy of the contour and its symmetry.

What we have is an object that, three dimensionally as one piece, could be compared in shape to a small sofa. The seat is a contour that blends into the walls of the arms and the back. I checked the contour using the profile gauge along three axes of its length, starting at the blend radius near the back and ending near the tangency point, which blended smoothly where the contour radius meets the front. The wire radius gauge was not the best way to determine the accuracy of this piece. When adjusting the wires at one

position on the block and moving to another position, the gauge could be reseated on the contour, but questions could be raised as to whether the hand that positioned it compensated for some inaccuracy in the contour. However, placing the parallel at several axial positions on the contour, I found the surface of this artifact to be extremely precise. At one point near a crack in the piece, there was light showing through, but the rest of the piece allowed very little to show.

F

IGURE

24.

Contoured Block of Granite

During this time, I had attracted quite a crowd. It is difficult to traverse the Giza Plateau at the best of times without getting attention from the camel drivers, donkey riders, and purveyors of trinkets. It was not long after I had pulled the tools out of my backpack that I had two willing helpers, Mohammed and Mustapha, who were not at all interested in compensation. At least that is what they told me, although I can say that I literally lost my shirt on that adventure. I had washed sand and dirt out of the corner of the larger block and used a white T-shirt that I was carrying in my backpack to wipe the corner out so I could get an impression of it with forming wax. Mustapha talked me into giving him the shirt before I left, and I was so inspired by what I had found I tossed it to him. My other helper, Mohammed, held the wire gauge at different points along the contour while I took photographs of it. I then took the forming wax and heated it with a matchâkindly provided by the Movenpick hotelâthen pressed it into the corner blend radius. I shaved off the splayed part and positioned it at different points around. Mohammed held the wax still while I took photographs. By this time there were an old camel driver and a policeman on a horse looking on.

What I discovered with the wax was a uniform radius, tangential with the contour, the back, and the side wall. When I returned to the United States, I measured the wax using a radius gauge and found that it was a true radius measuring 7/16 inch. This, I believe, is a significant finding, but it was not the only one. The side (arm) blend radius, I found, has a design feature that is a common engineering practice today. The ancient machinists had cut a relief at the corner, a technique that modern engineers

use

to allow a mating part with a small radius to match or butt up against a surface with a larger blend radius. This feature provides for a more efficient machining operation because it allows the use of a cutting tool with a large diameter and, therefore, a large radius. This means that the tool has greater rigidity, and more material can be removed when making a cut.

I believe there is more, much more, that can be gleaned from ancient artifacts using these and other methods of study. I am certain that the Cairo Museum contains many artifacts that when properly analyzed will lead to the same conclusion that I have drawn from this pieceâmodern craftspeople and the ancient Egyptians have much in common in their use of the same

kinds of machining techniques. The evidence, from granite artifacts at Giza and other locations, that ancient craftspeople used high-speed motorized machinery, and what we might call modern techniques in nonconventional machining such as ultrasonics, warrants serious study by qualified, openminded people who can approach the subject without prejudice or preconceived notions.

The implications of such discoveries are tremendous in terms of a more thorough understanding of the level of technology employed by the ancient pyramid builders. We are not only presented with hard evidence that seems to have eluded us for decades and that provides support for the theory that the ancients were technically advanced. We are also provided with an opportunity to reanalyze history and the evolutionâand devolutionâof civilizations from a different perspective. But our understanding of

how

something was made opens up a different dimension when we then try to determine

why

it was made.

The precision in these artifacts is irrefutable. Even if we ignore the question of how they were produced, we are still faced with the question of why such precision was needed. Revelation of new data invariably raises new questions. In this case it is understandable for skeptics to ask, "Where are the machines?" But machines are tools, and the question should be applied universally and can be asked of anyone who believes other methods may have been used. The truth is that no tools have been found to explain

any

theory on how the pyramids were built or the granite boxes were cut. More than eighty pyramids have been discovered in Egypt, and the tools that built them have never been found. Even if we accepted the notion that copper tools are capable of producing these incredible artifacts, the few copper implements that have been uncovered do not represent the number of such tools that would have been used if every stonemason who is supposed to have worked on the pyramids at just the Giza site owned one or two. In the Great Pyramid alone there are an estimated 2,300,000 blocks of stone, both limestone and granite, weighing between two-and-one-half tons and seventy tons each. That is a mountain of evidence, and there are no tools surviving to explain even this one pyramid's creation.

The principle of Occam's razor, where the simplest means of manufacturing holds force until proven inadequate, has guided my attempt to

understand the pyramid builders' methods. In the theory proposed by Egyptologists, the basic foundation of this principle is lacking. The fact is the simplest methods do not satisfy the evidence, and Egyptologists have been reluctant to consider other, less simple methods. There is little doubt in my mind that Egyptologists have seriously underestimated the ancient builders' capabilities. But they have only to look at the precision of the artifacts and the evidence for the mastery of machining technologies, which have been recognized in recent years, to find some answers. It would also help to try and understand modern manufacturing at the shop floor level. Primitive methods, though simple to grasp intellectually, simply do not work in the field, and researchers would be well-served by gaining a better understanding of more sophisticated, ultra-precise methods.

One reference point for judging a civilization as advanced is to compare it with our current state of manufacturing evolution. Manufacturing is the physical manifestation of a society's scientific and engineering imagination and efforts. For over a hundred years industry has progressed exponentially. Since Petrie first made his critical observations of Egyptian artifacts between 1880 and 1882, our civilization has leapt forward technologically at breakneck speed. But, the development of machine-tools has been intrinsically linked with the availability of consumer goods and manufacturers' desire to find a customer. Most of our manufacturing development has been directed at providing the consumer with goods, which are created by artisans. Over a hundred years after Petrie, some artisans are still utterly astounded by the achievements of the ancient pyramid builders. They are astounded not so much by what they perceive a society is capable of creating using primitive tools, but rather by comparing these prehistoric artifacts with their own current level of expertise and technological advancement. To be objective, I must recognize that there are some artisans and engineers who resist revising their beliefs for the same reasons many Egyptologists doâthey believe only "modern" societies are capable of sophisticated machining techniques. However, I would not be as bold in my assertions if I did not believe that the majority of my peers viewed the evidence with the same objectivity as I do and reached similar conclusions. I have presented this material to many engineers and artisans, and they are astonished at the evidence that is put before them.

To fully appreciate the value of this kind of research, we should keep in mind that the interpretation and understanding of a civilization's level of technology has predominately hinged on the preservation of written records. But for the majority of us, the nuts-and-bolts of our society do not always make interesting reading; in the same way, an ancient stone mural will more than likely have been cut to convey an ideological message rather than to preserve the information regarding the technique used to inscribe it. Moreover, the records of technology developed by our modern civilization rest in media that is vulnerable and could conceivably cease to exist in the event of a worldwide catastrophe, such as a nuclear war or another ice age. Our legacy will likely be read in the tangible remains of our society. Consequently, after several thousand years, someone looking back would most probably arrive at a more accurate interpretation of us and our society from our artisans'

methods

rather than an interpretation of our

language. The language of science and technology does not have the same freedom as does speech.

So even though the Egyptian tools and machines have not survived the thousands of years since their use, we have to assume, by objective analysis of the evidence for them left behind in the artifacts, that these tools did indeed exist.