The Giza Power Plant (15 page)

F

IGURE

21.

Petrie's Valley Temple Core & Hole

The fact that the feedrate evenly spirals along the length of the granite cores is quite remarkable considering the proposed method of cutting. The taper indicates an increase in the cutting surface area of the drill as it cut deeper, hence an increase in the resistance. A uniform feed under those conditions, using manpower, would be impossible. Petrie's theory of a ton or two of pressure being applied to a tubular drill consisting of bronze inset with jewels does not take into consideration that under several thousand pounds of pressure the jewels would undoubtedly work their way into the softer substance (the bronze), leaving the granite relatively unscathed after the attack. Nor does this method explain the groove being deeper through the quartz.

It should be noted that Petrie did not identify the means by which he inspected the core, whether he used metrology instruments, a microscope, or the naked eye. It also should be noted that Egyptologists do not universally accept his conclusions.

In Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries

,

A. Lucas takes issue with Petrie's conclusion that the grooves were the result of fixed jewel points. He wrote:

In my opinion, to suppose the knowledge of cutting these gem stones to form teeth and of setting them in the metal in such a manner that they would bear the strain of hard use, and to do this at the early period assigned to them, would present greater difficulties than those explained by the assumption of their employment. But were there indeed teeth such as postulated by Petrie? The evidence to prove their presence is as follows.

(a) A cylindrical core of granite grooved round and round by a graving point, the grooves being continuous and forming a spiral, with in one part a single groove that may be traced five rotations round the core.

(b) Part of a drill hole in diorite with seventeen equidistant grooves due to the successive rotation of the same cutting point.

(c) Another piece of diorite with a series of grooves ploughed out to a depth of over one-hundredth of an inch at a single cut.

(d

)

Other pieces of diorite showing the regular equidistant grooves of a saw.

(e) Two pieces of diorite bowls with hieroglyphs incised with a very free-cutting point and neither scraped nor ground out.

But if an abrasive powder had been used with soft copper saws and drills, it is highly probable that pieces of the abrasive would have been forced into the metal, where they might have remained for some time, and any such accidental and temporary teeth would have produced the same effect as intentional and permanent

ones. . . .

9

Lucas went on to speculate that the workers withdrew the tube-drill in order to remove waste and insert fresh grit into the hole, thereby creating the grooves. However, there are problems with this theory. It is doubtful that

a simple tool that is being turned by hand would remain turning while the artisans draw it out of the hole. Likewise, placing the tool back into a clean hole with fresh grit would not require that the tool rotate until it was at the workface. There also is the question of the taper on both the hole and the core. Both would effectively provide clearance between the tool and the granite, thereby making sufficient contact to create the grooves impossible under these conditions.

In contrast, ultrasonic drilling fully explains how the holes and cores found in the Valley Temple at Giza could have been cut, and it is capable of creating all the details that Petrie and I puzzled over. Unfortunately for Petrie, ultrasonic drilling was unknown at the time he made his studies, so it is not surprising that he could not find satisfactory answers to his queries. In my opinion, the application of ultrasonic machining is the only method that completely satisfies logic, from a technical viewpoint, and explains all noted phenomena.

Ultrasonic machining is the oscillatory motion of a tool that chips away material, like a jackhammer chipping away at a piece of concrete pavement, except much faster and not as measurable in its reciprocation. The ultrasonic tool bit, vibrating at 19,000-to 25,000-cycles-per-second (hertz), has found unique application in the precision machining of odd-shaped holes in hard, brittle material such as hardened steels, carbides, ceramics, and semiconductors. An abrasive slurry or paste is used to accelerate the cutting

action.

10

The most significant detail of the drilled holes and cores studied by Petrie was that the groove was cut deeper through the quartz than through the feldspar. Quartz crystals are employed in the production of ultrasonic sound and, conversely, are responsive to the influence of vibration in the ultrasonic ranges and can be induced to vibrate at high frequency. When machining granite using ultrasonics, the harder material (quartz) would not necessarily offer more resistance, as it would during conventional machining practices. An ultrasonically vibrating tool bit would find numerous sympathetic partners, while cutting through granite, embedded right in the granite itself. Instead of resisting the cutting action, the quartz would be induced to respond and vibrate in sympathy with the high-frequency waves and amplify the abrasive action as the tool cut through it.

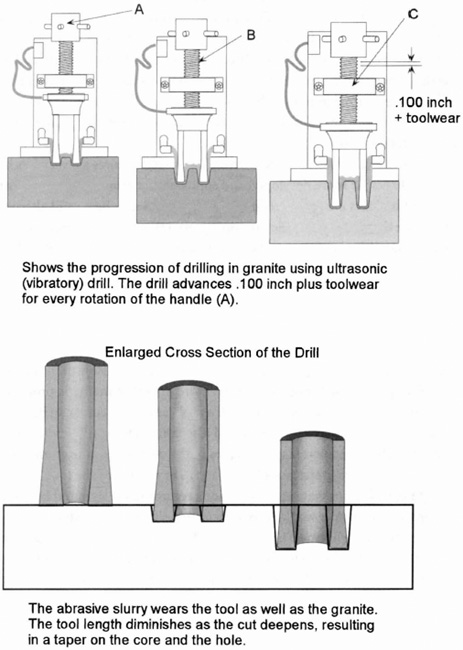

The tapering sides of the hole and the core are perfectly normal when we consider the basic requirement for all types of cutting tools. This requirement is that clearance be provided between the tool's nonmachining surfaces and the workpiece. Instead of having a straight tube, therefore, we would have a tube with a wall thickness that gradually became thinner along its length. The outside diameter becomes gradually smaller, creating clearance between the tool and the hole, and the inside diameter becomes larger, creating clearance between the tool and the central core. This would allow a free flow of abrasive slurry to reach the cutting area. By using a tube-drill of this design, the tapering of the sides of the hole and the core is explained. Typically this type of tube-drill is made of softer material than the abrasive, and the cutting edge would gradually wear away. The dimensions of the hole, therefore, would correspond to the dimensions of the tool at the cutting edge. As the tool became worn, the hole and the core would reflect this wear in the form of a taper (see Figure 22).

The requirement for advancing an ultrasonic tool into a workpiece is for the cutting edge of the tool to apply pressure to the workpiece as the vibratory motion of the tool does the actual cutting. This can be accomplished two ways: The tool can plunge straight down, or it can be screwed into the workpiece. We can explain the spiral groove if we select the latter method as the most likely one used. It should be made clear that the rotational speed of the drill is not a major factor in this cutting method; it is merely a means to advance the drill and apply pressure to the workpiece. Using a screw-and-nut method, the tube-drill could be efficiently advanced into the workpiece by turning it in a clockwise direction (see Figure 22). The screw would gradually thread through the nut, forcing the oscillating drill into the granite. It would be the ultrasonically induced motion of the drill that would do the cutting, not the drill-bit's rotation. The latter would be needed only to sustain a cutting action at the workface. By definition, the process is not a drilling process by conventional standards, but a grinding process in which abrasives are caused to impact the material in such a way that a controlled amount of material is removed.

The fact that there is a groove at all in the Valley Temple core may be explained several ways. An uneven flow of energy may have caused the tool to oscillate more on one side than the other, the tool may have been improperly

mounted, or a buildup of abrasive on one side of the tool may have cut the groove as the tool spiraled into the granite.

FIGURE 22.

Ultrasonic Drilling of Granite

Another method by which the grooves could have been created was through the use of a spinning trepanning tool that had been mounted off-center to its rotational axis. Clyde Treadwell of Sonic Mill Inc. explained to me that when an off-centered drill rotated into the granite, it would gradually be forced into alignment with the rotational axis of the drilling machine's axis. The grooves, he claimed, could be created as the drill was rapidly withdrawn from the hole.

If Treadwell's theory is the correct one, it still requires a level of technology that is far more developed and sophisticated than what the ancient pyramid builders are given credit for. This method may be a valid alternative to the theory of ultrasonic machining, even though ultrasonics resolves all the unanswered questions where other theories have fallen short. When we search for a single method that provides an answer for all the data, we find that neither primitive nor most conventional machining methods provide that answer; consequently, we are forced to consider methods that are cutting-edge technologies even in our own time.

It goes without saying that further studies need to be made. One way to decide between opposing theories is to replicate the cores using the advanced machining methods I propose and the more primitive methods proposed by some Egyptologists. Following such a replication, the cores can be compared using metrology equipment and a scanning electron microscope in order to detect the microscopic changes in the structure of the granite that can result from the pressure and heat exerted or created by the tool. I doubt many Egyptologists share my conclusions regarding the pyramid builders' drilling methods, so it would be beneficial to perform these tests in order to prove conclusively the most likely method the builders used for cutting stone.

As this book was being prepared for publication, I received an unexpected e-mail from

NOVA'

s stonemason, Roger Hopkins, who had read my article about ancient Egyptian technology on the Internet. He wrote:

Dear Chris,

You are a voice in the wilderness. I just finished reading your article about stone working techniques in ancient Egypt. I am a stonemason

by trade and in 1991 the PBS series NOVA invited me to go to Egypt to experiment with building a pyramid; I quickly got bored with working the soft limestone and started to ponder the granite work. Here in Massachusetts, my specialty is working in granite (see my web page:

http://tiac.net/uÂsers/rhopkins

).

When I was asked by the Egyptologists how the ancients could have produced this work with mere copper tools, I told them they were crazy and that they were using at least state-of-art techniques. [At] first glance I tend to agree with you about the ultrasonic core hole drilling. I do enough core hole drilling to know that the embedded scrape marks would not be the result of ordinary core drilling. . . . I would love to explore this technique further with you and perhaps do a presentation in our next film about Egypt. . . .

Sincerely,

Roger Hopkins

In my subsequent communications with Hopkins, I found him to be very honest and straightforward regarding the techniques used by the ancients. His account of the building of the

NOVA

pyramid was much the same as that reported by Mark Lehner. He asked my permission to pursue the ultrasonic drilling aspects, as it was my idea, and I told him the more the merrier. The more people who are looking into how the ancient Egyptians accomplished their prodigious feats the better chance we have of determining the truth. Moreover, like any good businessman, Hopkins sees the potential for applying this technology in his own work.

My last e-mail from Hopkins informed me that he had contacted people at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology about pursuing this theory, had received promising feedback, and he would keep me informed. So the chapter on the ultrasonic drilling of Egyptian granite is at an end, even as this theory faces a new beginning.

Chapter Five

AMAZING DISCOVERY AT GIZA

I

n February

1995,

I joined Graham Hancock and Robert Bauval

in Cairo to participate in a documentary. While there, I came across and measured some artifacts produced by the ancient pyramid builders that prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that highly advanced and sophisticated tools and methods were employed by this ancient civilization. Two of the artifacts in question are well-known; another is not, but it is more accessible, since it is lying out in the open, partly buried in the sand of the Giza Plateau. For this trip to Egypt I had taken along some instruments with which I had planned to inspect features I had identified during my 1986 trip. The instruments were:

- A "parallel"âa

flat ground piece of steel about six-inches long and one-quarter-inch thick. The edges are ground flat within .0002 inch. - An Interapid indicator

(known as a clock gauge by my British compatriots). - A wire contour gaugeâa

device once used, before the advent of computer numerical controlled machining, by die-makers to form around shapes. - Hard forming wax.

I had taken along the contour gauge to check the inside of the mouth of the Southern Shaft inside the King's Chamber, for reasons to be discussed in a forthcoming chapter. Unfortunately, I found out after getting there that things had changed since my last visit. In 1993, a fan was installed inside this opening and, therefore, it was inaccessible to me and I was unable to check it. I had taken the parallel for quick checking of the surface of granite artifacts to determine their precision. The indicator was to be attached to the parallel

for further inspection of suitable artifacts. Though the indicator did not survive the rigors of international travel, the instruments with which I was left were adequate for me to form a conclusion about the precision to which the ancient Egyptians were working.

Finding the King's Chamber in the Great Pyramid crowded with tourists, and not having the access I wanted to the Southern Shaft, I headed over to the Second Pyramid to inspect the "sarcophagus" there. Petrie had remarked that this granite box, like the one inside the King's Chamber, would had to have been installed in the bedrock chamber from above, before the chamber was roofed over and the pyramid finished, as it was too large to fit through the entrance passage. He supported his conclusion by pointing out that the bedrock chamber had gabled limestone beams that were put in place after the box was installed. Petrie's measurements of the passage were 41.08 to 41.62 inches wide by 47.13 to 47.44 inches high, and his dimensions of the box were 103.68 inches outside length, 41.97 inches outside width, 38.12 inches outside height; 84.73 inches inside length, 26.69 inches inside width, and 29.59 inches inside

depth.

1

I.E.S. Edwards gave the angle of the entrance passage

as 25°55'.depth.

2

Petrie may have been correct in his assumptions, depending on how the smaller sloping passage is vertically oriented with the larger horizontal passage. Petrie was comparing the width of the box to the width of the passage, and obviously it will not fit. However, the box

will

fit into the smaller entrance passage if it is turned on its side. The only question not answered is whether there is enough room for it to tilt where the sloping passage meets the horizontal passage. It is unfortunate these questions were not on my mind at the time I was inside the pyramid, but my mission, at that time, involved other aspects of the ancient pyramid builders' work.

Crouching through the entrance passage and into the bedrock chamber, I climbed inside the box andâwith a flashlight and the parallelâwas astounded to find the surface on the inside of the box perfectly smooth and perfectly flat. Placing the edge of the parallel against the surface I shone my flashlight behind it. No light came through the interface. No matter where I moved the parallelâvertically, horizontally, sliding it along as one would a gauge on a precision surface plateâI could not detect any deviation from a perfectly flat surface.

A group of Spanish tourists found my activity extremely interesting,

and they gathered around me as I animatedly demonstrated my discovery while exclaiming into my tape recorder, "Space-age precision!" The tour guides were becoming quite animated, too. I sensed that they probably did not think it was appropriate for a live foreigner to be where they believed a dead Egyptian should go, so I respectfully removed myself from the sarcophagus and continued my examination visually from the outside of the box.

There were more features of this artifact that I wanted to inspect, of course, but I did not have the freedom to do so. The corner radii on the inside appeared to be uniform all around, with no variation of precision of the surface to the tangency point. I was tempted to take a wax impression, but the hovering guides expecting bribes (baksheesh) inhibited this activity. (I was on a very tight budget.)

My mind was racing as I lowered myself into the narrow confines of the entrance shaft and climbed to the outside of the pyramid. The inside of a huge granite box had been finished off to an accuracy that modern manufacturers reserve for precision surface plates. How did the ancient Egyptians achieve this? And why did they do it? Why did they find that box so important that they would go to such trouble? It would be impossible to do that kind of work on the inside of an object by hand. Even with modern machinery it would be a very difficult and complicated task! Another point to consider was that the box, and the one in the King's Chamber inside the Great Pyramid, did not have to be made out of one piece if the only purpose it served was to house a dead body. There is evidence in the Cairo Museum proving that the ancient Egyptians also constructed sarcophagi out of five pieces and a lid. So why did they find it necessary to create each of these two boxes out of single blocks, which required the extra planning and effort to lower them into their chambers rather than drag them through the passages?

Petrie stated that the mean variation of the dimensions of the box in the Second Pyramid was .04 inch. Not knowing where the variation he measured was, I am not going to make any strong assertions except to say that it is possible to have an object with geometry that varies in length, width, and height and still maintain perfectly flat surfaces. Surface plates are ground and lapped to within .0001 to .0003 inch, depending on the grade of the specific surface plate; however, the thickness may vary more than the .04 inch that Petrie noted on that sarcophagus. A surface plate, though, is a single

surface and would represent only one outside surface of a box. Moreover, the equipment used to rough and finish the inside of a box would be vastly different than that used on the outside. It would be much more problematic to grind and lap the inside of a box to the accuracy I had observed which would result in a precise and flat surface to the point where the flat surface meets the corner radius. The physical and technical problems associated with such a task are not easy to solve. One could use drills to rough the inside out, but when it comes to finishing a box of this size with an inside depth of 29.59 inches, while maintaining a corner radius of less than one-half inch, one would have to overcome some significant challenges.

While being extremely impressed with this artifact, I was even more impressed with other artifacts found at another site in the rock tunnels at the temple of Serapeum at Saqqara, the site of the Step Pyramid and Zoser's Tomb. I had followed Hancock and Bauval on their trip to this site for a filming on February 24, 1995. We were in the stifling atmosphere of the tunnels, where the dust kicked up by tourists lay heavily in the still air. These tunnels contain twenty-one huge granite and basalt boxes. Each box weighs an estimated sixty-five tons, and, together with the huge lid that sits on top of it, the total weight of each assembly is around one hundred tons. Just inside the entrance of the tunnels was an unfinished lid, and beyond this lid, barely fitting within the confines of one of the tunnels, was a granite box that also had been rough hewn.

The granite boxes were approximately 13-feet long, 7-1/2-feet wide, and 11-feet high. They were installed in "crypts" that were cut out of the limestone bedrock at staggered intervals along the tunnels. The floors of the crypts were about four feet below the tunnel floor, and the boxes were set into recesses in the center. Bauval had commented earlier about the engineering aspects of installing such huge boxes within a confined space where the last crypt was located near the end of the tunnel. With no room for the hundreds of slaves pulling on ropes to position these boxes, how were they moved into place?

While Hancock and Bauval were filming, I jumped down into a crypt and placed my parallel against the outside surface of the box. It was perfectly flat. I shone the flashlight and found no deviation from a perfectly flat surface. I clambered through a broken-out edge into the inside of another giant

box and, again, I was astonished to find it astoundingly flat. I looked for errors and could not find any. I wished at that time that I had the proper equipment to scan the entire surface and ascertain the full scope of the work. Nonetheless, I was perfectly happy to use my flashlight and straightedge and stand in awe of this incredibly precise and incredibly huge artifact. Checking the lid and the surface on which it sat, I found them both to be perfectly flat. It occurred to me that this gave the manufacturers of this piece a perfect sealâtwo perfectly flat surfaces pressed together, with the weight of one pushing out the air between the two surfaces. The technical difficulties in finishing the inside of that piece made the sarcophagus in Khafra's Pyramid seem simple in comparison. Canadian researcher Robert McKenty was accompanying me at this time. He saw the significance of the discovery and was filming with his camera. At that moment I knew how Howard Carter must have felt when he discovered Tutankhamen's tomb.

The dust-filled atmosphere in the tunnels made breathing uncomfortable. I could only imagine what it would be like if I were a craftsman finishing off a piece of granite in that tunnel; regardless of the method I used, it would be unhealthy work. Surely it would have been better to finish the work in the open air? I was so astonished by this find that it did not occur to me until later that the builders of these relics, for some esoteric reason, intended for them to be ultra precise. They had gone to the trouble to take the unfinished product into the tunnel and finish it underground for a good reason. It is the logical thing to do if you require a high degree of precision in the piece that you are working. To finish it with such precision at a site that maintained a different atmosphere and a different temperature, such as in the open under the hot sun, would mean that when it was finally installed in the cool, cavelike temperatures of the tunnel, the workpiece would lose precision. The granite would give up its heat, and in doing so change its shape through contraction. The solution then as now, of course, was to prepare precision objects in a location that had the same heat and humidity in which they were going to be housed.

This discovery, and the realization of its critical importance to the artisans that built it, went beyond my wildest dreams of discoveries to be made in Egypt. For a man of my inclination, this was better than King Tut's tomb. The Egyptians' intentions with respect to precision are perfectly clear, but to

what end? Further studies of these artifacts should include thorough mapping and inspection with the following tools:

- A laser for checking surface flatnessâ

typically used for aligning precision machine beds. - An ultrasonic thickness gaugeâ

to check the thickness of the walls to determine their consistency to uniform thickness. - An optical flat with monochromatic light sourceâ

to determine if the surfaces really are finished to optical precision.

I have contacted four precision granite manufacturers in the United States and not one can do this kind of work. In correspondence with Eric Leither of Tru-Stone Corp., I discussed the technical feasibility of creating several Egyptian artifacts, including the giant granite boxes found in the bedrock tunnels at the temple of Serapeum at Saqqara (see Figure 23). He responded as follows:

Dear Christopher,

First I would like to thank you for providing me with all the fascinating information. Most people never get the opportunity to take part in something like this. You mentioned to me that the box was derived from one solid block of granite. A piece of granite of that size is estimated to weigh 200,000pounds if it was Sierra White granite which weighs approximately 175 lb. per cubic foot. If a piece of that size was available, the cost would be enormous. Just the raw piece of rock would cost somewhere in the area of $115,000.00. This price does not include cutting the block to size or any freight charges. The next obvious problem would be the transportation. There would be many special permits issued by the D.O.T. and would cost thousands of dollars. From the information that I gathered from your fax, the Egyptians moved this piece of granite nearly 500 miles. That is an incredible achievement for a society that existed hundreds of years ago.