The Giza Power Plant (14 page)

If the operators of the saw, in an attempt to correct a mistake, had tilted their blade in the manner described above, the saw lines would show a difference from the pre-error saw lines because they would be at an angle. The mistakes in the granite were found on the north side of the coffer, and Petrie observed that the saw lines on that side were horizontal. Following Petrie's footsteps, in 1986 I was able to verify his observations of the coffer in the Great Pyramid. The saw lines on the side where the mistakes were made are all horizontal, invalidating any argument proposing that the mistake was overcome by tilting the blade, which is probably the only method that would be successful using a handsaw. This evidence points to the distinct probability that the pyramid builders possessed motorized machinery when they cut the granite found inside the Great Pyramid and the Second Pyramid.

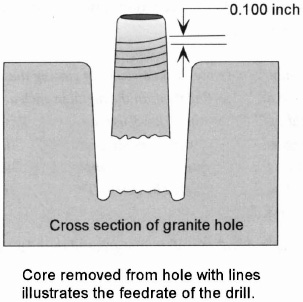

Today these saw marks would reflect either the differences in the aggregate dimensions of a wire bandsaw with the abrasive, or the side-to-side movement of the wire, or the wheels that drive the wire. The result of any of these conditions is a series of slight grooves. The feedrate and either the distance between the variation in length of the saw or the diameter of the wheels determine the distance between the grooves. The distance between the grooves on the coffer inside the King's Chamber is approximately .050 inch.

Along with the evidence on the outside of the King's Chamber coffer, we find further evidence of the use of high-speed machine tools on the

inside of the granite coffer. The methods that were evidently used by the pyramid builders to hollow out the inside of the granite coffers are similar to the methods that would be used to machine out the inside of components today. Tool marks on the coffer's inside indicate that when the granite was hollowed out, workers made preliminary roughing cuts by drilling holes into the granite around the area that was to be removed (see Figure 18). According to Petrie, those drill holes were made with tube-drills, which left a central core that had to be knocked away after the hole had been cut. After all the holes had been drilled and all the cores removed, Petrie surmised that the coffer was then handworked to its desired dimension. The machinists on that particular piece of granite once again let their tools get the better of them, and the resulting errors are still to be found on the inside of the coffer. As Petrie noted, "On the E. inside is a portion of a tube-drill hole remaining, where they had tilted the drill over into the side by not working it vertically. They tried hard to polish away all that part, and took off about 1/10 inch thickness all around it ; but still they had to leave the side of the hole 1/10

deep, 3 long, and 1.3 wide; the bottom of it is 8 or 9 below the original top of the coffer. They made a similar error on the N. inside, but of a much less extent. There are traces of horizontal grinding lines on the W.

inside."

5

F

IGURE

18.

Tube-drilling a Granite Box

The errors Petrie noted are not uncommon in modern machine shops, and I must confess to having made them myself on occasion. Several factors could be involved in creating this condition, although I cannot visualize any one of them being a hand operation. Once again, while working their drill into the granite, the machinists had made a mistake before they had time to correct it.

Let us speculate for a moment that the drill was being worked by hand. How far into the granite would the Egyptian craftspeople have been able to cut before the drill had to be removed to permit cleaning the waste out of the hole? Would they be able to drill eight or nine inches into the granite without having to remove their drill? It is inconceivable to me that they could have achieved such a depth with a hand-operated drill without the frequent withdrawal of the drill to clean out the hole or without their making provisions for the removal of the waste while the drill was still cutting. By frequently withdrawing the drill, however, they would have been able to expose their error and notice the direction their drill was taking before it had cut a .200-inchgouge into the side of the coffer and before it had reached a depth of eight or nine inches. The same situation applies as easily with the drill as with the sawâa high-speed operation made an error before the operators had time to correct it.

Although the ancient Egyptians are not given credit for having the wheel, the fact is that archaeological evidence, when evaluated with a machinist's eye, proves that they not only had the wheel, but they used it in very sophisticated ways. The evidence of lathe work is markedly distinct on some of the artifacts housed in the Cairo Museum, as well as those that were studied by Petrie. And if the Egyptians indeed used a lathe, then they had developed the wheel, for the products turned on a lathe, being circular, have the elements of being wheelsâin fact, the wheels that are used on locomotives are turned on lathes. So although the lathes used by the ancient Eygptians have long disappeared, Petrie was very clear that they had existed when he identified the marks of true lathe turning on two pieces of diorite in his collection. It is true that intricate objects can be created without the aid of machinery

simply by rubbing the material with an abrasive such as sand or using a piece of bone or wood to apply pressure. The relics Petrie was looking at, however, in his words, "could not be produced by any grinding or rubbing process which pressed on the

surface."

6

F

IGURE

19.

Petrie's Bowl Shards

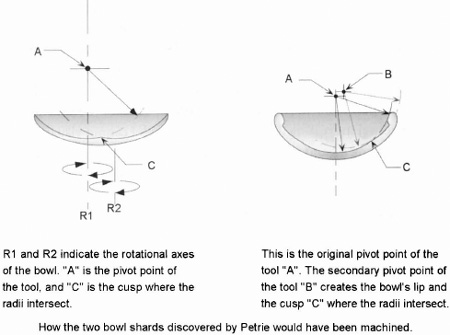

The simple rock bowl shards Petrie was studying would hardly be considered remarkable to the inexperienced eye. However, Petrie, devoting as much care to the observation of this artifact (a) as he did to others, found that the spherical concave radius forming the dish had an unusual feel to it. Upon closer examination, he detected a sharp cusp where two radii intersected, indicating that the radii were cut on two separate axes of rotation (see Figure 19).

I have witnessed the same condition when a component has been removed from a lathe and then worked on again without being recentered properly. On examining other pieces from Giza, Petrie found another bowl shard that had the marks of true lathe turning (b). This time, though, instead of shifting the workpiece's axis of rotation, a second radius was cut by shifting the pivot point of the tool. With this radius, they machined just

short of the perimeter of the dish, leaving a small lip. Again, a sharp cusp defined the intersection of the two radii.

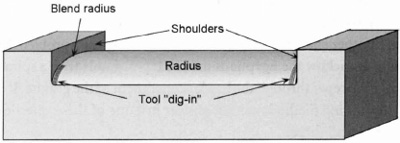

While browsing through the Cairo Museum, I found evidence of lathe turning on a large scale. A sarcophagus lid had distinct lathe turning marks. The radius of the lid terminated with a blend radius at shoulders on both ends. The tool marks near these corner radii were the same as those I have observed when turning an object with an intermittent cut. The tool is deflected under pressure from the cut, and then relaxes when the section of cut is finished. When the workpiece comes round again to the tool, the initial pressure causes the tool to dig in. As the cut progresses, the amount of "dig in" is diminished. On the sarcophagus lid in the Cairo Museum, tool marks indicating these conditions were exactly where one would expect to find them (see Figure 20).

Egyptian artifacts representing tubular drilling are clearly the most astounding and conclusive evidence yet presented to indicate the extent to which machining knowledge and technology were practiced in prehistory. The ancient pyramid builders used a technique for drilling holes that is commonly known as "trepanning." This technique leaves a central core and is an efficient means of hole making. When making holes that did not go all the way through the material, the workers drilled to the desired depth and then broke the core out of the hole. Trepanning was evident not only in the holes that Petrie studied, but on the cores cast aside by the masons who had done the work. Regarding tool marks that left a spiral groove on a core taken out of a hole drilled into a piece of granite, Petrie wrote, "On the granite core, No.7, the spiral of the cut sinks .1 inch in the circumference of 6 inches, or

1 in 60, a rate of ploughing out of the quartz and feldspar which is

astonishing."

7

After reading this, I had to agree with Petrie. This was an incredible feedrate (distance traveled per revolution of the drill) for drilling into any material, let alone granite. I was completely confounded as to how a drill could achieve this feedrate. Petrie was so astounded by these artifacts that he attempted to explain them at three different points in one chapter of his

book.

8

To an engineer in the 1880s, what Petrie was looking at was an anomaly. The characteristics of the holes, the cores that came out of them, and the tool marks would be an impossibility according to any conventional theory of ancient Egyptian craftsmanship, even with the technology available in Petrie's day. Three distinct characteristics of the hole and core, as illustrated in Figure 21, make the artifacts extremely remarkable:

F

IGURE

20.

Sarcophagus Lid in the Cairo Museum

- A taper on both the hole and the core.

- A symmetrical helical groove following these tapers showing that the drill advanced into the granite at a feedrate of .10 inch per revolution of the drill.

- The confounding fact that the spiral groove cut deeper through the quartz than through the softer feldspar.

In conventional machining the reverse would be the case. In 1983 Donald Rahn of Rahn Granite Surface Plate Co. told me that diamond drills, rotating at nine hundred revolutions per minute, penetrate granite at the rate of one inch in five minutes. In 1996, Eric Leither of Tru-Stone Corp. told me that these parameters have not changed since then. The feedrate of modern drills, therefore, calculates to be .0002 inch per revolution, indicating that the ancient Egyptians drilled into granite with a feedrate that was five hundred times greater or deeper per revolution of the drill than modern drills! The other characteristics of the artifacts also pose a problem for modern drills. Somehow the Egyptians made a tapered hole with a spiral groove that was cut deeper through the harder constituent of the granite. If conventional machining methods cannot answer just one of these questions, how do we answer all three?

For those who may still believe in the "official" chronology of the historical development of metals, identifying copper as the metal the ancient

Egyptians used for cutting granite is like saying that aluminum could be cut using a chisel fashioned out of butter. What follows is a more feasible and logical method, and it provides an answer to the question of techniques the ancient Egyptians may have used in all aspects of their work.