The Ghost in the Machine (48 page)

sharpen our awareness. The public is aware that there is a problem;

it is not aware of the magnitude and the urgency of the problem; it is

not aware that we are moving towards a climax which is not centuries,

but only a few decades ahead -- that is, well within the lifetime

of the present generation of teenagers. What I am trying to prove

is not that the situation is hopeless, but that it is indeed unique,

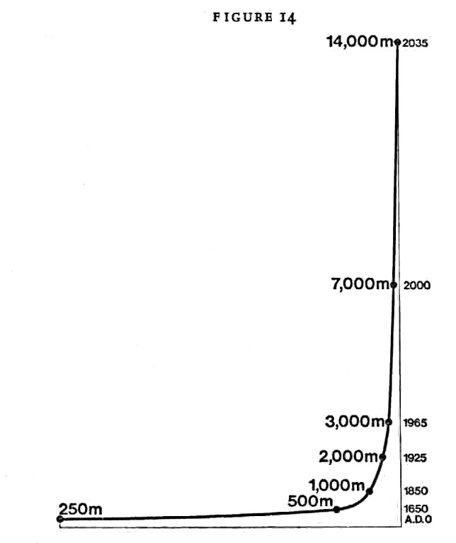

unprecedented in man's history. De Beer's parable of the aeroplane which

skims along the runway for thousands of miles, but within a mile or two

from takeoff changes into a rocket, shooting straight up into the sky,

is meant to illustrate what the mathematician calls an 'exponential curve'

(Figure 14).

miles on end, along which its rise would only be discernible through

a microscope. Then comes the critical moment when Pasteur et al. took

the brakes off. The brakes, of course, symbolise the high mortality rate

which, balancing the 'lift' of the birth rate, kept the population curve

nearly horizontal. It took about a century -- half an inch on our scale

-- until the consequences became apparent; from then onward the curve

rises steeper and steeper, until, in the second half of our century, it

starts rocketing towards the sky. It took our species something like a

hundred thousand years to spawn its first billion. Today we are adding

a further billion to the total every twelve years. In the first few

decades of the next century, if the present trend continues, we shall

add a billion every six years. After that, every three years; and so

on. But long before that de Beer's crazy aeroplane is bound to crash.

Population curve from the beginning of the Christian era

extrapolated to 2035 A.D.

got out of hand. Even the draughtsman attempting to extend the curve

into the future will be defeated because, as the curve gets steeper and

steeper, he must run out of paper -- as the world must run out of food,

of Lebensraum, of beaches and river shores, of privacy, of smiles.

our time -- not only the population explosion, but also the explosion

in power, communications, and specialised knowledge.

'As measured by manpower, number of periodicals or number of scientific

papers, science is growing exponentially with a doubling time of about

fifteen years. Figure 1 shows the increase of scientific journals since

they began in 1665. . . .' The figure shows a curve similar to the one

above, indicating that the number of scientific journals in 1700 was

less than ten, in 1800 around a hundred, in 1850 around a thousand,

in 1900 more than ten thousand, after the First World War around a

hundred thousand, and by A.D. 2000 is expected to reach the one million

mark. 'The same picture is obtained if the number of scientists or

scientific papers is measured, and appears to be comparable for widely

different scientific disciplines. During the past fifteen years, the same

number of scientists were produced as existed during the entire previous

period of science. Thus because the average working life of a research

scientist is about forty-five years, seven out of every eight scientists

who have ever lived are alive now. Similarly, almost

ninety per

cent

of all scientific endeavour has been undertaken during the past

fifty years.' [7] The United States National Education Authority sets

the doubling time since 1950 even lower: ten years. [8]

Cro Magnon to about five thousand years ago. With the invention of the

lever, the pulley and other simple mechanical devices, the muscular

strength of man would appear multiplied, say, five- or tenfold; then

the curve would again remain nearly horizontal until the invention of

the steam engine and the Industrial Revolution, just two hundred years

ago. From then on, it is the same story as before: takeoff, steeper and

steeper climb to the rocket-like stage. The exponential increase in the

speed of communications, or in the range of penetration into the depths

of the universe by optical and radio telescopes, is too well known to

need stressing; but the following illustration is perhaps less familiar.

about half a million electron-volts of energy; in the 1930s we could

accelerate them to twenty million electron-volts; by 1950 to five hundred

million; and at the time of writing, an accelerator of fifty thousand

million electron-volts is under construction. But more bemusing than

all these figures is to me an episode in 1930, when I nearly lost my job

as a science editor because of indignant protests against an article I

wrote on the progress in rocketry, in which I predicted space travel 'in

our lifetime'. And a year or two before the first Sputnik was launched,

Britain's Astronomer Royal made the immortal statement: 'Space travel is

bilge.' Our imagination is willing to accept that things are changing,

but unable to accept the

rate

at which they are changing, and to

extrapolate into the future. The mind boggles at an exponential curve as

Pascal's mind boggled when, in the Copernican universe, infinity opened

its gaping jaws:

Le silence éternel de ces espaces infinis

m'effraie.

extrapolate into the future, partly because we are frightened, mainly

because of the poverty of our imagination.

compare the chart which we have just discussed, showing the explosive

increase in people, knowledge, power and communications, with another

type of chart indicating the progress of social morality, ethical

beliefs, spiritual awareness and related values. This chart will field

a curve of quite different shape. It, too, will show a very slow rise

during the nearly flat prehistoric miles; then it will oscillate with

inconclusive ups and downs through what we call civilised history; but

shortly after the exponential curves get airborne, the 'ethical curve'

shows a pronounced downward trend, marked by two World Wars, the genocidal

enterprises of several dictators, and new methods of terror combined

with indoctrination, which can hold whole continents in their grip.

but not an over-dramatised view of our history. They represent the

consequences of man's split mind. The exponential curves are all, in

one way or another, the work of the new cortex; they show the explosive

results of learning at long last how to actualise its potentials which,

through all the millermia of our prehistory, have been lying dormant. The

other curve reflects the delusional streak, the persistence of misplaced

devotion to emotional beliefs dominated by the archaic paleo-mammalian

brain.

What is called human progress is a purely intellectual affair, made

possible by the enormous development of the forebrain. Owing to this,

man was able to build up the symbolic worlds of speech and thought,

and some progress in science and technology during the 5000 years

of recorded history was made.

Not much development, however, is seen on the moral side. It is

doubtful whether the methods of modern warfare are preferable to the

big stones used for cracking the skull of the fellow-Neanderthaler.

It is rather obvious that the moral standards of Laotse and Buddha

were not inferior to ours. The human cortex contains some ten

billion neurons that have made possible the progress from stone axe

to airplanes and atomic bombs, from primitive mythology to quantum

theory. There is no corresponding development on the instinctual

side that causes man to mend his ways. For this reason, moral

exhortations, as proffered through the centuries by the founders of

religion and great leaders of humanity, have proved disconcertingly

ineffective. [9]

and emotional development, take the contrast between communication

and co-operation. Progress of the means of communication is again

reflected by an exponential curve: crowded within a single century are

the invention of steam-ship, railway, motor car, air-ship, aeroplane,

rocket, space-ship; of telegraph, telephone, gramophone, radio, radar;

of photography, cinematography, television, telstar. . . . The month I

was born, the Wright brothers in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, managed for

the first time to stay in the air for one entire minute in their flying

machine; the chances are that before I die we shall have reached the

moon and perhaps Mars.

No generation of man ever before has witnessed

in its lifetime such changes.

so that instead of Jules Verne's Eighty Days, it can be orbited in

eighty minutes. But as to the second curve -- the bridging of the

distance between nations did not bring them 'closer' to each other

-- rather the opposite. Before the communications-explosion, travel

was slow, but there existed no Iron Curtain, no Berlin Wail, no mine

fields in no-man's-lands, and hardly any restrictions on immigration or

emigration; today about one-third of mankind is not permitted to leave

its own country. One. could almost say that progress in co-operation

varied in reverse ratio to progress in communications. The conquest of

the air transformed limited into total warfare; the mass media became

the demagogue's instruments of fomenting hatred; and even between close

neighbours like England and France, the increase in tourist traffic has

hardly increased mutual understanding. There have been some positive

advances such as the European Common Market; they are minute compared

to the gigantic cracks which divide the planet into three major and

countless minor, hostile, isolated camps.

general pattern. Language, the outstanding achievement of the neocortex,

became a more dividing than unifying factor, increasing intra-specific

tensions; progress in communications followed a similar trend of turning

a blessing into a curse. Even from the aesthetic point of view we have

managed to contaminate the luminiferous ether as we have contaminated

our air, rivers and seashores; you fiddle with the dials of your radio

and from all over the world, instead of celestial harmonies, the ether

disgorges its musical latrine slush.

is the most spectacular and the best known. To sum it up as briefly as

possible: after the First World War, statisticians calculated that on

the average ten thousand rifle bullets or ten artillery shells had been

needed to kill one enemy soldier. The bombs dropped from flying machines

weighed a few pounds. By the Second World War, the block-busters had

acquired a destructive power equal to twenty tons of T.N.T. The first

atomic bomb on Hiroshima equalled twenty thousand tons of T.N.T. Ten

years later, the first hydrogen bomb equalled twenty million tons. At the

time of writing, we are stockpiling bombs the equivalent of one hundred

million tons of T.N.T.; and there are rumours of a 'gigaton bomb' --

a 'nuclear weapon packing the power of a billion tons of T.N.T. that

could be detonated a hundred miles off the U.S. coastline and still set

off a fifty-foot tidal wave that would sweep across much of the entire

American continent . . . or a cobalt bomb that would send a deadly cloud

sweeping forever about the earth.' [10]

time 'unique'. The first is quantitative, expressed by the exponential

increase of populations, communications, destructive power, etc. Under

their combined impact, an extra-terrestrial intelligence, to whom

centuries are as seconds, able to survey the whole curve in one sweep,

would probably come to the conclusion that human civilisation is either

on the verge of, or in the process of, exploding.

before the thermonuclear bomb, man had to live with the idea of his death

as an individual; from now onward, mankind has to live with the idea of its

death as a species.

Other books

Tambourines to Glory by Langston Hughes

The Price of Hannah Blake by Donway, Walter

Charles Manson Now by Marlin Marynick

Another part of the wood by Beryl Bainbridge

Remember When 2 by T. Torrest

The Island - Part 2 (Fallen Earth) by Stark, Michael

Fallen Eden by Williams, Nicole

A Promise of Forever by M. E. Brady

Erased by Jennifer Rush

Sleep Talkin' Man by Karen Slavick-Lennard