The Flamingo’s Smile (28 page)

Read The Flamingo’s Smile Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

The nature of the

sinus pudoris

had generated a lively debate, with partisans on both sides claiming eyewitness support. One party held that the

sinus

was simply an enlarged part of the ordinary genitalia; others called it a novel structure found in no other race. Some even described the so-called “Hottentot apron” as a large fold of skin hanging down from the lower abdomen itself.

Cuvier was determined to resolve this old argument; the status of Saartjie’s

sinus pudoris

would be the primary goal of his dissection. Cuvier began his monograph by noting: “There is nothing more famous in natural history than the

tablier

(the French rendering of

sinus pudoris

) of Hottentots, and, at the same time, no feature has been the object of so many arguments.” Cuvier resolved the debate with his usual elegance: the

labia minora

, or inner lips, of the ordinary female genitalia are greatly enlarged in Khoi-San women, and may hang down three or four inches below the vagina when women stand, thus giving the impression of a separate and enveloping curtain of skin. Cuvier preserved his skillful dissection of Saartjie’s genitalia and wrote with a flourish: “I have the honor to present to the Academy the genital organs of this woman prepared in a manner that leaves no doubt about the nature of her

tablier

.” And Cuvier’s gift still rests in its jar, forgotten on a shelf at the Musée de l’Homme—right above Broca’s brain.

Yet while Cuvier correctly identified the nature of Saartjie’s

tablier

, he fell into an interesting error, arising from the same false association that had inspired public fascination with Saartjie—sexuality with animality. Since Cuvier regarded Hottentots as the most bestial of people, and since they had a large

tablier

, he assumed that the

tablier

of other Africans must become progressively smaller as the darkness of southern Africa ceded to the light of Egypt. (In the last part of his monograph, Cuvier argues that the ancient Egyptians must have been fully Caucasian; who else could have built the pyramids?)

Cuvier knew that female circumcision was widely practiced in Ethiopia. He assumed that the

tablier

must be at least half-sized among these people of intermediate hue and geography; and he further conjectured that Ethiopians excised the

tablier

to improve sexual access, not that circumcision represented a custom sustained by power and imposed upon girls with genitalia not noticeably different from those of European women. “The negresses of Abyssinia,” he wrote, “are inconvenienced to the point of being obliged to destroy these parts by knife and cauterization” (

par le fer et par le feu

, as he wrote in more euphonious French).

Cuvier also told an interesting tale, requiring no comment in repetition:

The Portuguese Jesuits, who converted the King of Abyssinia and part of his people during the 16th century, felt that they were obliged to proscribe this practice [of female circumcision] since they thought that it was a holdover from the ancient Judaism of that nation. But it happened that Catholic girls could no longer find husbands, because the men could not reconcile themselves to such a disgusting deformity. The College of Propaganda sent a surgeon to verify the fact and, on his report, the reestablishment of the ancient custom was authorized by the Pope.

I needn’t burden you with any detailed refutation of the general arguments that made the Hottentot Venus such a sensation. I do, however, find it amusing that she and her people are, by modern convictions, so singularly and especially unsuited for the role she was forced to play.

If earlier scientists cast the Khoi-San peoples as approximations to the lower primates, they now rank among the heroes of modern social movements. Their languages, with complex clicks, were once dismissed as a guttural farrago of beastly sounds. They are now widely admired for their complexity and subtle expression. Cuvier had stigmatized the hunter-gatherer life styles of the traditional San (Bushmen) as the ultimate degradation of a people too stupid and indolent to farm or raise cattle. The same people have become models of righteousness to modern ecoactivists for their understanding, nonexploitive, and balanced approach to natural resources. Of course, as Guenther argues in his article on the Bushman’s changing image, our modern accolades may also be unrealistic. Still, if people must be exploited rather than understood, attributions of kindness and heroism sure beat accusations of animality.

Furthermore, while Cuvier’s contemporaries sought physical signs of bestiality in Khoi-San anatomy, anthropologists now identify these people as perhaps the most paedomorphic of human groups. Humans have evolved by a general retardation (or slowing down) of developmental rates, leaving our adult bodies quite similar in many respects to the juvenile, but not to the adult, form of our primate ancestors—an evolutionary result called paedomorphosis, or “child shaping.” On this criterion, the greater the extent of paedomorphosis, the further away from a simian past (although minor differences among human races do not translate into variations in mental or moral worth). Although Cuvier searched hard to find signs of animality in Saartjie’s lip movements or in the form of her leg bone, her people are, in general, perhaps the least simian of all humans.

Finally, the major rationale for Saartjie’s popularity rested on a false premise. She fascinated Europeans because she had big buttocks and genitalia and because she supposedly belonged to the most backward of human groups. Everything fit together for Cuvier’s contemporaries. Advanced humans (read modern Europeans) are refined, modest, and sexually restrained (not to mention hypocritical for advancing such a claim). Animals are overtly and actively sexual, and so betray their primitive character. Thus, Saartjie’s exaggerated sexual organs record her animality. But the argument is, as our English friends say (and quite literally in this case), “arse about face.” Humans are the most sexually active of primates, and humans have the largest sexual organs of our order. If we must pursue this dubious line of argument, a person with larger than average endowment is, if anything, more human.

On all accounts—mode of life, physical appearance, and sexual anatomy—London and Paris should have stood in a giant cage while Saartjie watched. Still, Saartjie gained her posthumous triumph. Broca inherited not only Cuvier’s preparation of Saartjie’s

tablier

, but her skeleton as well. In 1862, he thought he had found a criterion for arranging human races by physical merit. He measured the ratio of radius (lower arm bone) to humerus (upper arm bone), reasoning that higher ratios indicate longer forearms—a traditional feature of apes. He began to hope that objective measurement had confirmed his foregone conclusion when blacks averaged .794 and whites .739. But Saartjie’s skeleton yielded .703 and Broca promptly abandoned his criterion. Had not Cuvier praised the arm of the Hottentot Venus?

Saartjie continues her mastery of Mr. Broca today. His brain decomposes in a leaky jar. Her

tablier

stands above, while her well-prepared skeleton gazes up from below. Death, as the good book says, is swallowed up in victory.

Postscript

Since biological determinism won its prestige in spurious claims to objectivity via quantification (see my book,

The Mismeasure of Man

), and since Saartjie Baartman owed her oppression to this sociopolitical doctrine masquerading as science, I was amused to find that Francis Galton himself, the chief apostle of quantification (and hereditarianism), once used an ingenious technique to measure the extent of steatopygia on a Khoi-San woman. Galton, Darwin’s brilliant and eccentric cousin, believed that he could put anything into numbers. He once tried to quantify the geographic distribution of female beauty by the following dubious method (as described in his autobiography,

Memories of My Life

, 1909, pp. 315–316):

Whenever I have occasion to classify the persons I meet into three classes, “good, medium, bad,” I use a needle mounted as a pricker, wherewith to prick holes, unseen, in a piece of paper, torn rudely into a cross with a long leg. I use its upper end for “good,” the cross arm for “medium,” the lower end for “bad.” The prick holes keep distinct, and are easily read off at leisure. The object, place, and date are written on the paper. I used this plan for my beauty data, classifying the girls I passed in streets or elsewhere as attractive, indifferent, or repellent. Of course this was a purely individual estimate, but it was consistent, judging from the conformity of different attempts in the same population. I found London to rank highest for beauty; Aberdeen lowest.

His discreet method for steatopygia was, in my view, even more clever (and probably a good deal more accurate if all those high school trig proofs really work). In his

Narration of an Explorer in Tropical South Africa

, he writes (my thanks to Raymond B. Huey of the University of Washington for sending this passage to me):

The sub-interpreter was married to a charming person, not only a Hottentot in figure, but in that respect a Venus among Hottentots. I was perfectly aghast at her development, and made inquiries upon that delicate point as far as I dared among my missionary friends…I profess to be a scientific man, and was exceedingly anxious to obtain accurate measurements of her shape; but there was a difficulty in doing this. I did not know a word of Hottentot, and could never therefore have explained to the lady what the object of my foot-rule could be; and I really dared not ask my worthy missionary host to interpret for me. I therefore felt in a dilemma as I gazed at her form, that gift of bounteous nature to this favoured race, which no mantua-maker, with all her crinoline and stuffing, can do otherwise than humbly imitate. The object of my admiration stood under a tree, and was turning herself about to all points of the compass, as ladies who wish to be admired usually do. Of a sudden my eye fell upon my sextant; the bright thought struck me, and I took a series of observations upon her figure in every direction, up and down, crossways, diagonally, and so forth, and I registered them carefully upon an outline drawing for fear of any mistake; this being done, I boldly pulled out my measuring-tape, and measured the distance from where I was to the place she stood, and having thus obtained both base and angles, I worked out the results by trigonometry and logarithms.

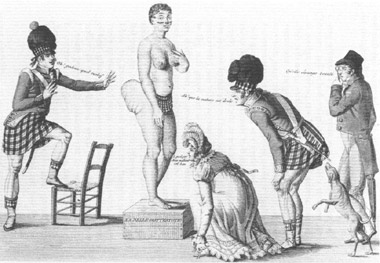

A satiric French print of 1812 commenting on English fascination with the Hottentot Venus. The soldier behind her examines her steatopygia, while the lady in front pretends to tie her shoelace in order to get a peek at Saartjie’s

tablier

.

Saartjie Baartman herself continues to fascinate us across the ages; her exploitation has never really ended. In an antiquarian bookstore in Johannesberg (see essay 12), I found and bought the following remarkable print (I still cannot view it without a shudder despite its intended humor, and I reproduce it here as a comment upon history and current reality that we dare not ignore). The print is a satirical French commentary (published in Paris in 1812) on English fascination with Saartjie’s display. It is titled:

Les curieux en extase, ou les cordons de souliers

(The curious in ecstasy, or the shoelaces). Spectators concentrate entirely upon sexual features of the Hottentot

Venus

. One military gentleman observes her steatopygia from behind and comments, “

Oh! godem quel rosbif

.” The second man in uniform and the elegantly attired lady are both trying to sneak a peak at Saartjie’s

tablier

. (This is the subtle point that an uninformed observer would miss. Saartjie displayed her buttocks but, following the customs of her people, would never uncover her

tablier

). The man exclaims “how odd nature is,” while the woman, hoping to get a better look from below, crouches under pretense of tying her shoes (hence the title). Meanwhile, the dog reminds us that we are all the same biological object under our various attires.

To bring the exploitation up to date, W.B. Deatrick sent me the cover of the French magazine

Photo

for May, 1982. It shows, naked, a woman who calls herself “Carolina, la Vénus hottentote de Saint-Domingue.” She holds an uncorked champagne bottle in front. The fizz flies up, over her head, through the letter O of the magazine’s title, down behind her back and directly into the glass, which rests, as she crouches (to mimic Saartjie’s endowment), upon her outstretched buttocks.

THE LORD REALLY

put it on the line in his preface to that prototype of all prescription, the Ten Commandments:

…for I, the Lord thy God, am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me (Exod. 20:5).

The terror of this statement lies in its patent unfairness—its promise to punish guiltless offspring for the misdeeds of their distant forebears.

A different form of guilt by genealogical association attempts to remove this stigma of injustice by denying a cherished premise of Western thought—human free will. If offspring are tainted not simply by the deeds of their parents but by a material form of evil transferred directly by biological inheritance, then “the iniquity of the fathers” becomes a signal or warning for probable misbehavior of their sons. Thus Plato, while denying that children should suffer directly for the crimes of their parents, nonetheless defended the banishment of a personally guiltless man whose father, grandfather, and great-grandfather had all been condemned to death.

It is, perhaps, merely coincidental that both Jehovah and Plato chose three generations as their criterion for establishing different forms of guilt by association. Yet we maintain a strong folk, or vernacular, tradition for viewing triple occurrences as minimal evidence of regularity. Bad things, we are told, come in threes. Two may represent an accidental association; three is a pattern. Perhaps, then, we should not wonder that our own century’s most famous pronouncement of blood guilt employed the same criterion—Oliver Wendell Holmes’s defense of compulsory sterilization in Virginia (Supreme Court decision of 1927 in

Buck

v.

Bell

): “three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

Restrictions upon immigration, with national quotas set to discriminate against those deemed mentally unfit by early versions of IQ testing, marked the greatest triumph of the American eugenics movement—the flawed hereditarian doctrine, so popular earlier in our century and by no means extinct today (see following essay), that attempted to “improve” our human stock by preventing the propagation of those deemed biologically unfit and encouraging procreation among the supposedly worthy. But the movement to enact and enforce laws for compulsory “eugenic” sterilization had an impact and success scarcely less pronounced. If we could debar the shiftless and the stupid from our shores, we might also prevent the propagation of those similarly afflicted but already here.

The movement for compulsory sterilization began in earnest during the 1890s, abetted by two major factors—the rise of eugenics as an influential political movement and the perfection of safe and simple operations (vasectomy for men and salpingectomy, the cutting and tying of Fallopian tubes, for women) to replace castration and other socially unacceptable forms of mutilation. Indiana passed the first sterilization act based on eugenic principles in 1907 (a few states had previously mandated castration as a punitive measure for certain sexual crimes, although such laws were rarely enforced and usually overturned by judicial review). Like so many others to follow, it provided for sterilization of afflicted people residing in the state’s “care,” either as inmates of mental hospitals and homes for the feebleminded or as inhabitants of prisons. Sterilization could be imposed upon those judged insane, idiotic, imbecilic, or moronic, and upon convicted rapists or criminals when recommended by a board of experts.

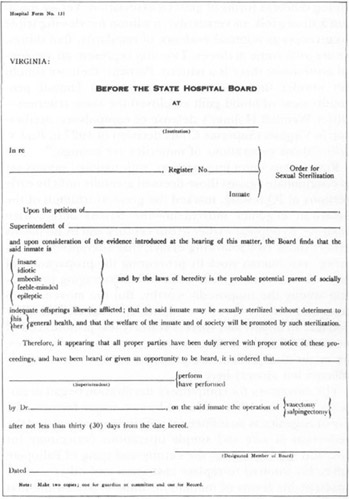

Official Virginia hospital form for sexual sterilization.

By the 1930s, more than thirty states had passed similar laws, often with an expanded list of so-called hereditary defects, including alcoholism and drug addiction in some states, and even blindness and deafness in others. These laws were continually challenged and rarely enforced in most states; only California and Virginia applied them zealously. By January 1935, some 20,000 forced “eugenic” sterilizations had been performed in the United States, nearly half in California.

No organization crusaded more vociferously and successfully for these laws than the Eugenics Record Office, the semiofficial arm and repository of data for the eugenics movement in America. Harry Laughlin, superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office, dedicated most of his career to a tireless campaign of writing and lobbying for eugenic sterilization. He hoped, thereby, to eliminate in two generations the genes of what he called the “submerged tenth”—“the most worthless one-tenth of our present population.” He proposed a “model sterilization law” in 1922, designed

to prevent the procreation of persons socially inadequate from defective inheritance, by authorizing and providing for eugenical sterilization of certain potential parents carrying degenerate hereditary qualities.

This model bill became the prototype for most laws passed in America, although few states cast their net as widely as Laughlin advised. (Laughlin’s categories encompassed “blind, including those with seriously impaired vision; deaf, including those with seriously impaired hearing; and dependent, including orphans, ne’er-do-wells, the homeless, tramps, and paupers.”) Laughlin’s suggestions were better heeded in Nazi Germany, where his model act inspired the infamous and stringently enforced

Erbgesundheitsrecht

, leading by the eve of World War II to the sterilization of some 375,000 people, most for “congenital feeblemindedness,” but including nearly 4,000 for blindness and deafness.

The campaign for forced eugenic sterilization in America reached its climax and height of respectability in 1927, when the Supreme Court, by an 8-1 vote, upheld the Virginia sterilization bill in

Buck

v.

Bell

. Oliver Wendell Holmes, then in his mid-eighties and the most celebrated jurist in America, wrote the majority opinion with his customary verve and power of style. It included the notorious paragraph, with its chilling tag line, cited ever since as the quintessential statement of eugenic principles. Remembering with pride his own distant experiences as an infantryman in the Civil War, Holmes wrote:

We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the state for these lesser sacrifices…. It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. Three generations of imbeciles are enough.

Who, then, were the famous “three generations of imbeciles,” and why should they still compel our interest?

When the state of Virginia passed its compulsory sterilization law in 1924, Carrie Buck, an eighteen-year-old white woman, lived as an involuntary resident at the State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded. As the first person selected for sterilization under the new act, Carrie Buck became the focus for a constitutional challenge launched, in part, by conservative Virginia Christians who held, according to eugenical “modernists,” antiquated views about individual preferences and “benevolent” state power. (Simplistic political labels do not apply in this case, and rarely in general for that matter. We usually regard eugenics as a conservative movement and its most vocal critics as members of the left. This alignment has generally held in our own decade. But eugenics, touted in its day as the latest in scientific modernism, attracted many liberals and numbered among its most vociferous critics groups often labeled as reactionary and antiscientific. If any political lesson emerges from these shifting allegiances, we might consider the true inalienability of certain human rights.)

But why was Carrie Buck in the State Colony and why was she selected? Oliver Wendell Holmes upheld her choice as judicious in the opening lines of his 1927 opinion:

Carrie Buck is a feeble-minded white woman who was committed to the State Colony…. She is the daughter of a feeble-minded mother in the same institution, and the mother of an illegitimate feeble-minded child.

In short, inheritance stood as the crucial issue (indeed as the driving force behind all eugenics). For if measured mental deficiency arose from malnourishment, either of body or mind, and not from tainted genes, then how could sterilization be justified? If decent food, upbringing, medical care, and education might make a worthy citizen of Carrie Buck’s daughter, how could the State of Virginia justify the severing of Carrie’s Fallopian tubes against her will? (Some forms of mental deficiency are passed by inheritance in family lines, but most are not—a scarcely surprising conclusion when we consider the thousand shocks that beset us all during our lives, from abnormalities in embryonic growth to traumas of birth, malnourishment, rejection, and poverty. In any case, no fair-minded person today would credit Laughlin’s social criteria for the identification of hereditary deficiency—ne’er-do-wells, the homeless, tramps, and paupers—although we shall soon see that Carrie Buck was committed on these grounds.)

When Carrie Buck’s case emerged as the crucial test of Virginia’s law, the chief honchos of eugenics understood that the time had come to put up or shut up on the crucial issue of inheritance. Thus, the Eugenics Record Office sent Arthur H. Estabrook, their crack fieldworker, to Virginia for a “scientific” study of the case. Harry Laughlin himself provided a deposition, and his brief for inheritance was presented at the local trial that affirmed Virginia’s law and later worked its way to the Supreme Court as

Buck

v.

Bell

.

Laughlin made two major points to the court. First, that Carrie Buck and her mother, Emma Buck, were feebleminded by the Stanford-Binet test of IQ, then in its own infancy. Carrie scored a mental age of nine years, Emma of seven years and eleven months. (These figures ranked them technically as “imbeciles” by definitions of the day, hence Holmes’s later choice of words—though his infamous line is often misquoted as “three generations of idiots.” Imbeciles displayed a mental age of six to nine years; idiots performed worse, morons better, to round out the old nomenclature of mental deficiency.) Second, that most feeblemindedness resides ineluctably in the genes, and that Carrie Buck surely belonged with this majority. Laughlin reported:

Generally feeble-mindedness is caused by the inheritance of degenerate qualities; but sometimes it might be caused by environmental factors which are not hereditary. In the case given, the evidence points strongly toward the feeble-mindedness and moral delinquency of Carrie Buck being due, primarily, to inheritance and not to environment.

Carrie Buck’s daughter was then, and has always been, the pivotal figure of this painful case. I noted in beginning this essay that we tend (often at our peril) to regard two as potential accident and three as an established pattern. The supposed imbecility of Emma and Carrie might have been an unfortunate coincidence, but the diagnosis of similar deficiency for Vivian Buck (made by a social worker, as we shall see, when Vivian was but six months old) tipped the balance in Laughlin’s favor and led Holmes to declare the Buck lineage inherently corrupt by deficient heredity. Vivian sealed the pattern—

three

generations of imbeciles are enough. Besides, had Carrie not given illegitimate birth to Vivian, the issue (in both senses) would never have emerged.

Oliver Wendell Holmes viewed his work with pride. The man so renowned for his principle of judicial restraint, who had proclaimed that freedom must not be curtailed without “clear and present danger”—without the equivalent of falsely yelling “fire” in a crowded theater—wrote of his judgment in

Buck

v.

Bell:

“I felt that I was getting near the first principle of real reform.”

And so

Buck

v.

Bell

remained for fifty years, a footnote to a moment of American history perhaps best forgotten. Then, in 1980, it reemerged to prick our collective conscience, when Dr. K. Ray Nelson, then director of the Lynchburg Hospital where Carrie Buck had been sterilized, researched the records of his institution and discovered that more than 4,000 sterilizations had been performed, the last as late as 1972. He also found Carrie Buck, alive and well near Charlottesville, and her sister Doris, covertly sterilized under the same law (she was told that her operation was for appendicitis), and now, with fierce dignity, dejected and bitter because she had wanted a child more than anything else in her life and had finally, in her old age, learned why she had never conceived.

As scholars and reporters visited Carrie Buck and her sister, what a few experts had known all along became abundantly clear to everyone. Carrie Buck was a woman of obviously normal intelligence. For example, Paul A. Lombardo of the School of Law at the University of Virginia, and a leading scholar of

Buck

v.

Bell

, wrote in a letter to me:

As for Carrie, when I met her she was reading newspapers daily and joining a more literate friend to assist at regular bouts with the crossword puzzles. She was not a sophisticated woman, and lacked social graces, but mental health professionals who examined her in later life confirmed my impressions that she was neither mentally ill nor retarded.