The Flamingo’s Smile (25 page)

Read The Flamingo’s Smile Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Since chimps are, in general anatomical aspect, probably more similar to other primates than to humans, this conclusion requires some exaggeration of the humanlike qualities of Tyson’s pygmy. Quite unconsciously, I suspect, and for two quite different reasons, Tyson continually overemphasizes the human similarities and as often underestimates the relationship with apes.

For the first reason, Tyson simply and consistently favors the human side in ambiguous situations. Note particularly his statements on posture. Tyson’s chimp was brought to England from Angola and arrived both ill and very weak (it died within a few months and thus became available for Tyson’s dissection). He observed that it occasionally but rarely walked erect; Tyson’s chimp usually progressed, as great apes characteristically do, by walking on its knuckles—feet firmly on the ground but hands bent over. Tyson attributed this peculiar posture to its weakened state and insisted that its natural mode of locomotion must be erect on legs alone, as in humans—even though his empirical data identified knuckle walking as far more common:

When it went as a quadruped on all four, ’twas ackwardly; not placing the palm of the hand flat to the ground, but it walk’d upon it’s knuckles, as I observed it to do, when weak, and had not strength enough to support it’s body…. Walking on it’s knuckles, as our pygmie did, seems no natural posture; and ’tis sufficiently provided in all respects to walk erect.

We can’t blame Tyson for not knowing that great apes normally walk on their knuckles, for this most uncharacteristic pose for animals was not well described in his time. Still Tyson’s defense of upright (or humanlike) posture as the normal mode for chimps does seem a bit forced, conditioned more by preconceptions about intermediate status on the chain of being than by direct attention to raw data. Thus, in writing “we may safely conclude, that nature intended it a biped,” Tyson discusses the articulation of femur to pelvis and the “largeness of the heelbone in the foot, which being so much extended, sufficiently secures the body from falling backwards.” Yet in the same discussion he conveniently omits other anatomical features described earlier that might lead us to doubt upright posture—particularly the major differences in pelvic structure between chimps and humans, and the handlike foot with its short and weak big toe.

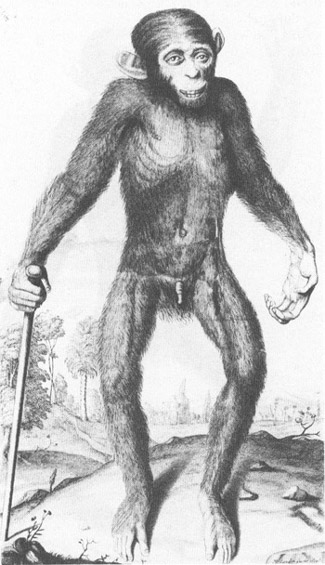

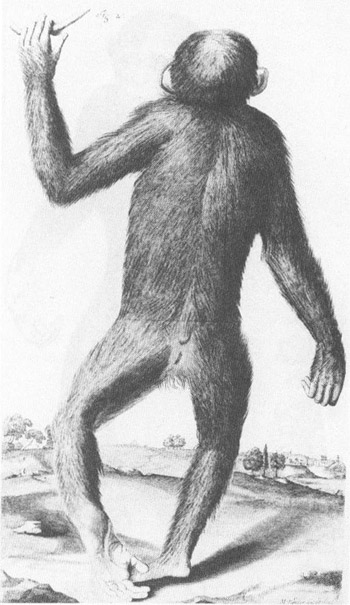

Since primates are visual animals, we must never omit (though historians often do) the role played by scientific illustrations in the formation of concepts and support of arguments. Tyson’s magnificent plates are all constructed to enhance the argument for upright posture, even in the absence of direct evidence for it (I include four reproductions with this essay). The first shows his pygmy from the front, standing fully erect, although note that Tyson cleverly provides it with a walking stick to indicate the difficulty that he couldn’t help observing in this mode of progress! Tyson writes: “Being weak, the better to support him, I have given him a stick in his right-hand.” The second plate depicts the chimp from the back, upright again, but this time holding on to a rope above its head for support! Finally, the plates of musculature and skeletal system are all portrayed in a fully upright human posture.

Front view of Tyson’s pygmie from his 1699 treatise. Note how he reconstructed the animal as walking erect to enhance its humanlike features. But it did not walk this way in life, so Tyson supplied a walking stick.

FROM TYSON

, 1699.

Back view of Tyson’s chimp, this time holding on to a rope for support.

FROM TYSON

, 1699.

In many other passages, Tyson awards almost human attributes and emotions to his pygmy. He recalls with delight, for example, how the chimp loved to wear clothes and put them on while in bed, although he noted that it never learned not to perform nature’s functions in the same place as well:

After our pygmie was taken, and a little used to wear cloaths, it was fond enough of them; and what it could not put on himself, it would bring in his hands to some of the company to help him to put on. It would lie in a bed, place his head on the pillow, and pull the cloaths over him, as a man would do; but was so careless, and so very a brute, as to do all nature’s occasions there.

Often, Tyson discussed the chimp’s behavior in purely human terms: “For I heard it cry myself like a child; and he hath been often seen to kick with his feet, as children do, when either he was pleased or angered.” In one passage, he even grants superiority to his chimp in matters of temperance:

Once it was made drunk with punch, (and they are fond enough of strong liquors) but it was observed, that after that time, it would never drink above one cup, and refused the offer of more than what he found agreed with him. Thus we see instinct of nature teaches brutes temperance; and intemperance is a crime not only against the laws of morality, but of nature too.

As a second reason for exaggerating similarities between his chimp and humans, Tyson made a crucial error. He knew that his pygmy was a young animal, for extremities of the long bones were still formed in cartilage and not fully ossified, but he regarded it as nearly full grown because he mistook the complete set of milk teeth for a permanent dentition (the baby teeth of great apes do, in some respects, resemble the permanent teeth of humans). Thus, he did not realize how young an animal—a baby almost—he was dissecting. (This misidentification also enhanced his subsequent error, in a philological treatise appended to his anatomy, of attributing classical legends and more modern reports of African Pygmies to the same animal, which he regarded as just over two feet tall when fully grown.)

I have often discussed in these essays the role of neoteny (literally, holding on to youth) in human evolution (see

Ever Since Darwin

and

The Panda’s Thumb

). We have evolved by slowing down the general developmental rates of primates and other mammals. Thus, human adults resemble juvenile chimps and gorillas much more closely than adult great apes. Consequently, the skeleton of a baby chimpanzee will retain many humanlike characters that an adult would lose—including a relatively large head (human babies, of course, also have relatively larger heads than human adults), a more upright mounting of the head on the spine (since the

foramen magnum

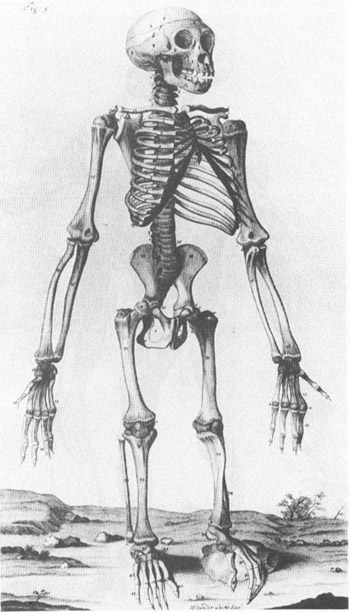

, or hole of articulation between skull and spinal column, moves back with growth), a more bulbous cranium (since the brain grows much more slowly than the body after birth), weaker brow ridges, and smaller jaws. Tyson’s plate of his pygmy’s skeleton, a remarkably accurate figure (I have seen photos of the original bones), shows all these humanlike features.

Tyson also noted all these features with delight in his text, but missed the coordinating theme—not that chimps are so like humans, but that he had dissected a very young animal and juvenile primates resemble adult humans in many ways, without demonstrating direct descent or relationship. He wrote, for example:

As for the face of our pygmie, it was liker a man’s than ape’s and monkeys faces are: for it’s forehead was larger, and more globous, and the upper and lower jaw not so long or prominent, and more spread; and it’s head more than as big again as either of theirs.

The skeleton of Tyson’s chimp, again with human-like features exaggerated in position of skull on spinal column, upright posture, and subtle details of proportions. A classic example of the use of illustration to demonstrate a point (or illustrate a bias).

FROM TYSON

, 1699.

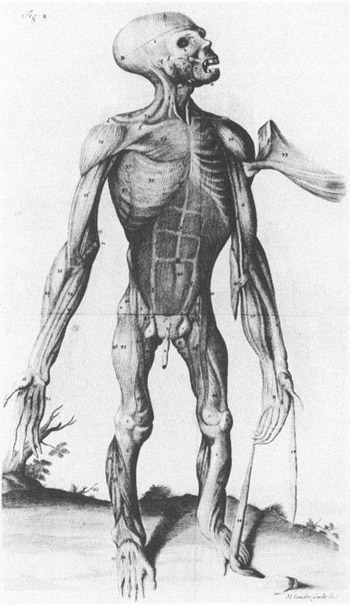

The musculature of Tyson’s chimp. The bizarre “peeling back” of exterior muscles (to show others within) was a convention of anatomical illustration at the time.

FROM TYSON

, 1699.

Indeed, the large and humanlike brain of Tyson’s chimp posed quite a problem. Tyson had already determined that the vocal apparatus of his pygmy was sufficiently similar to our own for speech, so why did it not talk? Perhaps a deficiency of brain prevented the expression of this most human attribute. Yet Tyson found little difference, either in basic structure or relative size, between his pygmy’s brain and our own.

One would be apt to think, that since there is so great a disparity between the soul of a man, and a brute, the organ likewise in which ’tis placed should be very different too. Yet by comparing the brain of our pygmie with that of a man, and with the greatest exactness, observing each part in both; it was very surprising to me to find so great a resemblance of the one to the other, that nothing could be more.

In a fascinating passage, displaying the seventeenth-century context of his work, Tyson simply denied that physical structure must provide a key to function. The brains are similar indeed, but humans possess some higher principle that potentiates the same matter in a different way:

There is no reason to think, that agents do perform such and such actions, because they are found with organs proper thereunto; for then our pygmie might be really a man. The organs in animal bodies are only a regular compages of pipes and vessels, for the fluids to pass through, and are passive. What actuates them, are the humours and fluids: and animal life consists in their due and regular motion in this organical body. But those nobler faculties in the mind of man, must certainly have a higher principle; and matter organized could never produce them; for why else, where the organ is the same, should not the actions be the same too?

If the chain of being had enduring value as a heuristic prod for the exploration of missing links, and if gaps grew greater as the chain advanced, then what about the chasm even more glaring than the one that Tyson thought he had filled between ape and human—between humans and angels or other celestial beings? Tyson gave the problem a cursory comment, more political than scientific, by suggesting in his dedicatory epistle to John Sommers, Lord High Chancellor of England and President of the Royal Society (publishers of his treatise), that men of such ample learning might well plug the gap themselves!

The animal of which I have given the anatomy, coming nearest to mankind; seems the nexus of the animal and rational, as your Lordship, and those of your High Rank and Order for knowledge and wisdom, approaching nearest to that kind of beings which is next above us; connect the visible, and invisible world.