The Fashionista Files (32 page)

CHAPTER 9

Money! Financing Your

Fashionista Habit and Battling

(or Preventing!) Bankruptcy

Fashionistas love to accumulate things: vintage cameos, the same pair of shoes in every color, jeans of almost identical hue, and six-figure credit card debt chief among them. Even the thriftiest fashionista cannot escape it. Fashionista assets are Balenciaga dresses, a very special Bruce vest, and Vivienne Westwood corsets (vintage!). When you consider the positive feelings that shopping and buying something new evokes, it can become easy to overlook things—like phone bills, taxes, the money you owe your best friend who loaned you a few hundred bucks when you were short—for the sake of getting the instant fix of fashion. We don’t own apartments, cars, or vacation homes. We don’t have 401(k)s or IRAs, and there’s a good chance we’ll probably spend our retirements as little old ladies who live in their (very expensive) shoes—or maybe just the boxes, which, of course, we always save.

Fashion may very well give you an instant high. But it can also be a harsh reality check, a means to confront some of your mental demons, especially the ones that revolve around money. It’s easy to feel like a failure when you can’t afford something. Money, in our society, tends to represent a measure of success. While the truth of success has nothing to do with dollar signs, we are still victims of a materialistic culture caught up in the throes of competition, oneupmanship, and “which handbag did you get this season?” pettiness. In the fashion industry, such pressures are hard to avoid.

In fact, being in the fashion industry really warps the mind. After years of writing about the decadence of $5,000 jackets, $2,500 cocktail dresses, and $1,200 evening wraps, career fashionistas, many of whom get 30 percent discounts from designer stores and have the privilege of receiving free gifts from designers and ordering things wholesale from showrooms, begin to see things that are still astronomically priced, like $1,000 dresses or sweaters, as affordable. Cheap even. We have witnessed many a fashionista picking up a pair of $295 shoes and cheering, “They’re practically free! I’ll take two!” just because they’re used to paying more like $500 for one pair. It’s not something to be proud of, this crazy sense of monetary value or lack thereof.

This chapter was not easy for us to write. We have both struggled (and continue to struggle) with money issues, especially in the fashion department. We’ve fielded calls from creditors, walked twenty blocks because we could afford to go only so far in a taxi (“Greene Street and Prince, please, but I only have six dollars, so you’ll have to stop the cab when you get to five dollars”), and had zero dollars in the bank. Just because this life has “worked” for us does not mean we recommend it. In fact, we

don’t

! We beseech fellow fashionistas to take it easy out there! The biggest tip we can provide is this: Never say, “I’m poor”; say, “I’m broke” instead. Remember: Broke is temporary. Poor is forever! Just like a bad sense of style.

The following pages will give you the inside scoop on ascertaining your financial situation (there are many different levels of sickness), financial tricks to get you through the fiscal fashion year, making money off of old clothes, dealing with your weakness, and balancing your checkbook—and your style needs. Not to mention a few skeletons from our closets that we’re not exactly proud of, but maybe you can learn from our mistakes!

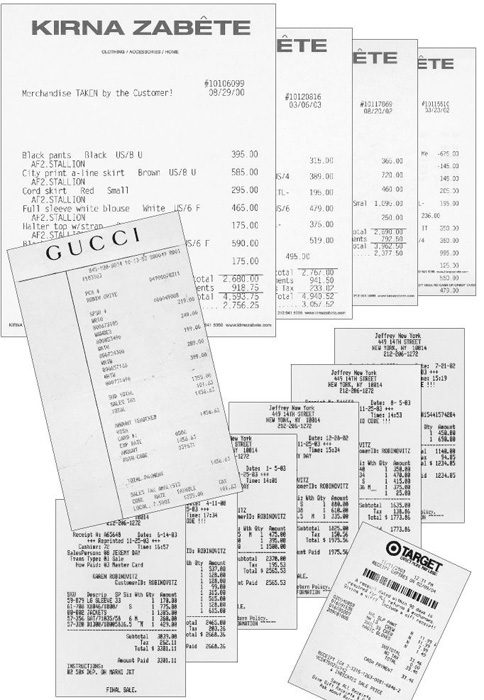

Our net worth in clothes

AWARENESS: ADMITTING YOU HAVE A PROBLEM IS HALF THE BATTLE

You Charge Me $150 per

Hour and Call This Advice?

KAREN

I was recently complaining to my therapist about the fact that I have no money. I wasn’t even sure how I’d pay her at the end of the month. It was one of those awful moments in life when I felt totally out of control, unsure how to handle my predicament and the fact that what I have in clothing, I lack in the bank.

I had twelve dollars to my name, and no one would ever have suspected it by the way I looked—like a million bucks. “I need to learn how to budget,” I told her, feeling truly helpless and doomed. “I spend way too much money. I never take public transportation. I go out to dinner every night. It’s bad,” I continued, trying to blame my situation on something other than my fashion addiction.

“I don’t think the problem is that,” my therapist said. “I think it may have something to do with your

shopping.

” My shopping? What? She started talking to me about learning to control myself. (Control?)

Then she looked at me from her brown leather reclining chair, her clog-clad feet perched perfectly on the ottoman, and proposed a probable solution: “I think you should consider limiting yourself to a certain amount of money each season and try to stay within that budget.” After a bit of a pause, she said, “Say, for example, three thousand dollars for spring.” Three thousand dollars! I looked at her in all seriousness and started cackling. Cackling! I recognize that for most people, $3,000 per season is an absurd amount of clothing, but for a fashionista who is powerless over enticingly pretty new trends and the latest version of the trench coat and who fancies things like $800 handbags and $500 shoes, $3,000 doesn’t get you much.

I scanned my outfit and quickly did some math. “I’m

wearing

three thousand dollars!” I said. The breakdown: $725 Balenciaga white jeans, $680 Gaultier shredded-leather biker top, $600 Pierre Hardy ankle boots, $300 Dean Harris gold hoop earrings, $900 Balenciaga handbag.

I was laughing, yes. But I was also mortified.

What has happened to me?

I thought. Where did my integrity go? I am no TFB (trust-fund baby). I do okay for myself, but I do not make

that

much money (in fact, some months I can barely pay my $300 cell phone bill). I have no right to be wearing these things, and yet I feel like I cannot survive without them. It was such a reality check. It was the first time that I really looked at myself and said, “I am a fashionista and I need help!”

Money to Burn

MELISSA

1996—I was broke. I had $45 in my wallet, $2 in my savings account, and $1 in my checking account. I had no credit cards, no bank cards, no department-store cards, and my debt was in the high five-figure range. Yet my tax returns insisted I should be an affluent member of society—someone who needs to put money in a condo, set up a tax shelter, invest in mutual funds, and generally be leading the good life.

Instead, I owned a closetful of designer clothes I hardly wore, an apartmentful of furniture for people I’ll never entertain, and absolutely nothing to show for the hundreds of thousands of dollars I’ve made except for multiple taxi receipts, torn dinner chits, club invitations, souvenir champagne corks, and maybe a Polaroid of me, drunk and completely decked out, smiling garishly into the flashing lights.

I was a debtor, and an insatiable one. At twenty-six, I hadn’t met a credit card I couldn’t charge to its maximum limit. Overdraft was my middle name. So was Over-the-limit. And Overspend. Of the fourteen credit cards I used to wield, ranging from the tacky (A&S) to the sublime (Bergdorf Goodman), not one of them has ever been paid on time . . . to be honest, not many were

paid,

period. Same goes at one time or another for rent, electricity, and phone bills. Because of my shopping habits, I’ve been almost evicted twice, threatened with arrest once, and was banned from opening a bank account in the state of New York.

Of my post-tax-and-401(k)-withholding income every two weeks, 95 percent was spent in the first

two

days upon joyous deliverance of such sum by direct deposit into my checking account. I was a pauper until the cycle begins itself again. When I found myself broke—which was often—I even resorted to turning in gift certificates for cash, Christmas presents for cash, Valentine’s Day presents for cash, selling jewelry for cash, and even the clothing off my back for cash. My life was a roller-coaster ride of feast or famine—dinner at the Four Seasons one evening, canned vegetables the next. I was never able to live within my means.

I had absolutely no idea what my “means” were. To find out, I was constantly adding and subtracting, multiplying and dividing, costs and expenses—not to balance my checkbook, of course, but to calculate how much I could spend before I had to starve. This was a necessary pastime of mine—calculating money. Everywhere in my apartment and in my office cubicle—on scraps of paper, on the backs of envelopes, laundry tickets, business cards, Post-its, scribbled in the pages of my Filofax, my sketchbook, my journal— marched a column of figures that calculated how much I had in my bank account, and exactly how much, after all the bills were paid and the rent was due and the food was bought—how much

exactly—

there was to

burn.

Most of the time the answer was “not nearly enough,” which was why I was in trouble. Because even with my meticulous calculations, I never quite paid off the obligatory bills, and instead threw it away on superfluous trivialities—a $900 Helmut Lang jacket, say, while the electric company threatened final disconnection, or else a $200 dinner the month I couldn’t pay the rent. To be homeless but cultured, poor but dressed divinely—it wasn’t an ambition; it was my lifestyle.

My one solace was that I was not alone in my heedlessness. There isn’t a great history of handling financial responsibility in my family. My grandfather was notorious for the pride he vested in his credit cards. He had about twenty of them, and kept them in an accordion-like cardholder in his wallet, so that he could pull them out and show them to strangers. Which he did. Usually on San Francisco BART trains, on his way to triple-X movie theaters in Oakland. “I’m very rich; I own my own business,” he’d tell passengers seated next to him. “Look at my credit cards. Macy’s. Saks. Visa Gold.”

Even if most of the credit cards had expired or were practically useless from maxed-out credit limits, and my grandfather had never owned a business of any kind, it didn’t stop him from thinking he was a rich man. My grandfather had grown up the second child of a wealthy Chinese family in Manila. He bought expensive clothes, and told strangers his father owned the largest movie theaters in Quezon City. He was heavily in debt, perennially on the verge of bankruptcy, and proud of his credit cards.

There’s a Filipino proverb that says people who spend a lot of money are “angry” at money—“

galit sa pera.

” They can’t stand to have it around. I know too many people who have declared bankruptcy. It’s they who came to mind when my phone rang at nine in the morning, with a shrill, piercing urgency that signaled the start of another round of a game I liked to call Dodging the Creditors. To combat this constant aggravation, I learned to answer my phone in Spanish.

“No entiendo, señor. ¿Habla Español?”

If they happened to catch me off guard and answering my phone in English, I developed a sick and perverse delight in telling them my “roommate” Melissa was out of the country, was working late, was never home, was dead. The last one scared me, and I didn’t do that again.

Like most debtors, my freefall down the rabbit hole started in college. It was probably a trip to Florida that did it. Not the real trip to South Beach I took my senior year—when three girlfriends and I holed up at the Cordozo Hotel, spent nights making eyes at swarthy waiters in Cuban restaurants, and generally had the liquor-soaked time of our lives, our $500 expenses paid for by our generous parents (mine included). No, not

that

Florida vacation, which ended with me, broke as usual, begging to borrow $25 from my best friend, Jennie, just so I could share a cab ride to our dormitory once we got to New York City.

“What would you do without me?” Jennie had asked. She was amused and a little annoyed, since we’d been down this road before. I didn’t know how to answer her. She was the one who had bailed me out the year before when the police

—the police—

called to say they were going to arrest me for a bounced check. Unless I coughed up the $115 I owed Canal Jeans in Soho for a pair of Doc Martens I’d purchased there, it was debtor’s prison for me (actually a desk-appearance ticket and a misdemeanor charge). Of course, I didn’t have the money. I couldn’t return the boots either, since they had been a present to the gay man I loved at the time. So Jennie lent me the money, and I paid her back with the hundred dollars my parents sent me that Thanksgiving so my sister and I could take the train to Washington and spend the holidays with relatives.

I made my sister take the bus instead. It was horrid—bus stations at Thanksgiving are filled with large caravans of military men, poor college kids like us, and the occasional bag lady with a free ticket home. It’s doubtful my sister will ever forgive me, although she’s had much practice. My sophomore year in college she lent me $900 to pay an overdue American Express bill. My credit history was virgin then: pure, solvent. At the time it seemed important to keep it that way. Aina, who was in high school, and boasted a fat savings account, sent me a MoneyGram plus $50 in cash to help me get through the month. The next month it was my parents who were stuck with the $1,500 AmEx bill. They weren’t as understanding.

My life is filled with such free associations—from one person who’s bailed me out of a money jam to another and another. I am bound to my friends and family not just by love but by debt. There is no limit to how much I owe them, and I owe some of them quite a lot. Lately I’ve come to realize how much they have learned to tolerate such shameless selfishness on my part. My reputation precedes me. Sometimes when I call, my friends don’t even bother to say “Hello,” only “How much?”

But back to Florida. The Florida vacation I

didn’t

take. The Florida vacation that started the cash-flow crisis I’m in now. It was my freshman year at college, the first day back from winter break. My roommate at the time was a girl named Madelyn, a prep-school princess with an enormous wardrobe and a fickle temperament. I liked Madelyn, and more important, I wanted her to like me.

“Let’s go to Florida,” she said one evening while we smoked cigarettes in the hallway and tried to affect cool.

“Sure,” I happily agreed. “Spring break?”

“No . . . tomorrow,” she suggested, flicking ash everywhere. “Classes don’t start for a couple days still. We could jet down, get an awesome tan, and be back for registration. Wouldn’t that be fun?” she asked.

“Tomorrow?” I repeated. “But what about the plane tickets? We’d have to pay premium for them. And where would we stay?”

Madelyn shrugged. “I’m sure it wouldn’t cost that much,” she said. “We could stay at a hotel or something. It’ll only be, like, a couple hundred bucks. It’s just a weekend,” she emphasized.

“Sure, sure.” I nodded, already perturbed. I only had a “couple hundred” bucks in my checking account at that point—money that was supposed to take me well into the semester. I’d spent almost my entire savings already, just to keep up with the Madelyns of my life.

We didn’t go to Florida. There was no way I’d have enough money or even the nonchalance to pull off that kind of stunt. Madelyn was nice about it: She pretended that it was okay for her to spend the week in a New York blizzard.

But her offhand suggestion was an eye-opener for me. It was the first time I fully comprehended the difference between Madelyn and me, rich versus poor, spontaneous versus anxious. For Madelyn, the world was an exciting place, full of endless possibilities. She could imagine flying off to Miami on a whim, just to get a good tan. For me, excitement meant a dinner downtown. At Benny’s Burritos.

I vowed I’d never have to cry poor again, that if I ever found myself in a similar situation, when a friend suggested blowing $200 on a magnum of Korbel, a table at Au Bar, a taxicab uptown, or even to “for God’s sake just buy the damn leather gloves”—I wouldn’t say no. I would be prepared. I intended to cultivate the seductive characteristics of rich, spoiled American girls. Ringing in my mind was a phrase from Tolstoy’s

War and Peace:

“Natasha, the rich girl with everything, was beloved by all. Self-sacrificing Sonya, who had nothing, was barren and forgotten.” I didn’t want to be Sonya, forever indebted and dependent. All my friends had Natasha’s wicked fire, her free spirit, her confident sense of entitlement—all of which I wanted to emulate. So I did. With a little help from my credit cards.

The next year I was armed to the teeth in plastic: MBNA Visa, MBNA Visa Gold, Chase Platinum, AmEx, Citibank Preferred. Too late, though—Madelyn never included me in any of her travel plans again.

Money. At the time I was half afraid and half amazed by the way I earned it—working forty hours a week at a software company, an art history major writing lines of code for customized computer programs. So I got rid of it before it consumed me. Before it defined me. Allowing myself to spend it all carelessly, recklessly, and with a certain wild abandon, leaving me poor and destitute after these manic bouts of spending, afforded me to retain the perverted sense of pride and identity I cultivated by being poor. Once I earned enough to renounce my hero worship of bitchy, thin girls with Daddy’s trust funds, I was actually proud of my erstwhile poverty. I didn’t want to save money or worry about it and lord it over other people. I found it was much easier to live with the anxiety of being broke than the anxiety of being rich.

It’s a misery, nonetheless, and one no amount of shopping sprees and fancy restaurants can solve. I was terribly unhappy. I didn’t clean my unpaid apartment for months, and grew accustomed to living in filth. My living room was overrun by laundry bags, empty gin bottles, stacks of unopened bills and glossy magazines. I threw large, raucous parties in my backyard garden, spending several hundred dollars on booze and food to entertain large groups of people who didn’t give a shit about me.