The Fashionista Files (28 page)

ART OFTEN REFERENCED IN FASHION

Pop Art. During 1950s and 1960s, it’s a movement that references consumer culture and everyday life in a graphic, colorful, almost cartoonlike style. Leading artists: Andy Warhol (most known for Campbell’s soup paintings and blocks of famous people with different background colors), Roy Lichtenstein (oversize comic book–like paintings), Keith Haring (all common things like hearts and simple drawings of colorful people, surrounded by sprouting lines meant to represent energy), and Robert Rauschenberg (magazine photos of current events turned into silk-screen prints, overlapped with paintbrush strokes).

Bauhaus. A modernist school of thought founded in 1919 in Weimar, Germany, by Walter Gropius, it integrates expressionist art with fields of architecture and design and was insistent upon being accessible to all socioeconomic brackets. Later, it was led by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who’s known for clean, sleek homes with stark glass that blend internal and external environments. Also, Mies van der Rohe is the creator of the ubiquitous Barcelona chairs. Bauhaus work is simple, functional, and often involves industrial material like steel, chrome, glass, and concrete. If something is affordable and clean, even utilitarian, proudly declare its Bauhaus roots.

Expressionism. To portray a subject matter in an emotionally charged way in which the artist sees it, rather than the way it is commonly seen. Leading artists: Wassily Kandinsky (1905–1940s), known for abstract intersecting shapes and sharp colors; and Jackson Pollock, known for splatter paint, which has often shown up on runway dresses (though he is considered to be among the abstract expressionist movement, whereby artists between the forties and sixties expressed themselves strictly through use of color and form).

Neoplasticism. A Dutch movement marked by Piet Mondrian, famous for rigid abstract shapes, horizontal and vertical lines, and a limited color palette. Yves Saint Laurent brought Mondrian’s work into mainstream fashion by referencing it in a series of mod dresses in 1965. L’Oréal knocked it off, too, for an ad campaign. You know, the graphic one with yellow, red, and black squares? Side note: Can also be used to describe plastic-surgery addicts who look

très

plastic.

Minimalism. A style of art that’s stripped down to its most basic form and shape. Leading artists: Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella, known for rectangular stripes and hard-core geometry. In the fashion world, minimalism is about basic shapes, stark colors, and clean modernism. Donna Karan and Calvin Klein specialize in this form.

Arts ’n’ Crafts. Similar to grade-school class, this is all about celebrating individual craftsmanship, which came about as a backlash reaction against the industrial revolution in Britain in the late nineteenth century. Textiles, stained glass, wallpaper, and things that have that “handmade at home” feeling were prevalent. Designers like Parkinson reflect this sensibility, as do raw-edged pieces, handmade unique fabrics, and patchwork.

THE CULTURATI

Feel Like Making Art

KAREN

At a swank party at the Paramount Hotel in Manhattan, I met Michael COLAVITO Hoiland, a long-haired photographer and painter with intense dark eyes. I had heard of him before, as he was shooting a big book for the NBA, using light infusion and abstract paintings in the work. He has done work commercially for Tiffany & Co., Sony, H.Stern, and the Gap. But in the art community, a discerning, often precarious place where haughty attitude reigns and critics shoot scathing comments like snipers, he is respected and admired—a feat for any artist.

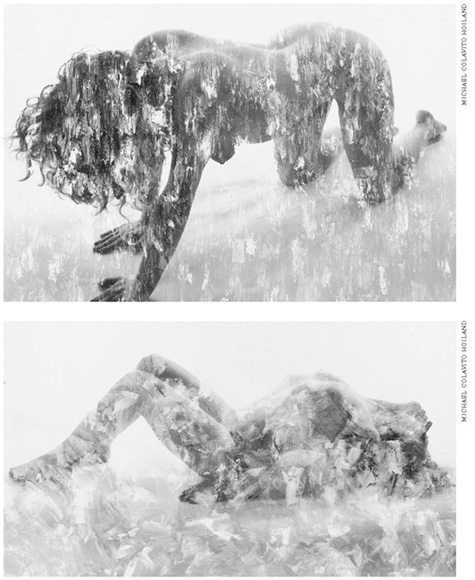

His pieces, ironically, are the epitome of postmodernism. Imagine an enormous silhouette of a woman. You can’t make out her face. But you can tell she has a certain kind of haircut and just how her nose is shaped. You can make out her body, her shape, her size. But instead of the creamy tone of her skin, her figure is filled with a sea of Gauguin-like heavy brushstrokes, a gorgeous wash of colors from an original painting or linear arrangements of rich hues. Serious art, his large pieces sell for over $100,000.

When you look at his creations, especially when they’re blown up to thirty feet long, you can’t help but be aroused. The women in the shots are sexy, portrayed in such a beautiful light. It’s not about T & A, gratuitous body parts, but rather the form and composition of a figure and how it relates to its space. His pieces are also intriguing. It’s hard to tell what his medium actually is. Is it a portrait? Is it a painting? It’s like, as hard as you try, you can’t quite figure out how he created it. He takes a photo of his paintings or sculptures, which are then fused with his photography. He shoots with an eight-by-ten-view camera—the kind that looks like an accordion—and, like a cartoon, uses it while covered with a black cloth. A purist, he does not use filters, computer images, or any shortcuts in his art, which is created entirely in camera on one original piece of film.

After I had been chatting with him for a few minutes, he asked if I would ever sit for him. I was floored. A typical female who often struggles with self-esteem issues about her looks, I thought,

What

are you, on crack? What could

you

possibly see in

me? I blew him off, I have to admit. I figured it was the champagne talking. He pursued me for months. Well, actually, his girlfriend, who knew me through a mutual friend, did. “Michael really wants to shoot you,” she kept saying. I still didn’t quite believe he remembered me clearly. Had he, he certainly wouldn’t want to shoot me! Not with these thighs and the belly that tends to protrude a little too much for my liking.

Finally, Michael and I sat down for lunch. He whipped out boxes of eight-by-ten chromes, original negatives of his work. They were breathtaking. Modern and yet classical, sexy without trying too hard. The women who posed for him were nude, but you could see nothing more than the outline of their bodies. After my trip to We Care, when I was feeling pretty darn good in my skin (and my jeans), I threw caution to the wind and scheduled a session with Michael, whose work was currently being considered by the Guggenheim. I figured, if anything, posing for him would be an excellent self-esteem boost.

I went to his studio, a stark space with big windows and nothing but enormous paintings, blowups of his painting/photography pieces, sculptures, and one crazy old-fashioned-looking supersized camera. There was a white backdrop waiting just for me. “Now what?” I said, wondering what I should do, knowing full well that the first thing I needed to do was disrobe for his camera. He, luckily, is very respectful, far from a gawking guy who uses art as a means to pick up chicks. He made concerted efforts to look only at my eyes as we spoke. And he talked lovingly about his girlfriend, probably his way of easing my mind.

When I stripped down, I was a nervous wreck.

What if he looks

at me and thinks,

“Naah . . . too fat,”

and asks me to leave?

All of the typical insecurities that go hand in hand with being naked with a man came to mind.

Ugh, my stretch marks. My hips are too big.

Could this be considered cheating on my boyfriend?

I wondered. At the same time, I really wanted to be there, to be a part of his art and something that lasts a lifetime and has deeper meaning than a great red jersey dress from the Celine cruise collection (even though I really want a great red jersey Celine dress from the cruise collection!).

I moved around on the cold white backdrop, thinking about what would be the most flattering position, wondering what in the hell I was doing naked in a studio in the first place. “Don’t move. Stay just like that.” I was trying to figure out how to pose and he caught me between postures—while I was on my hands and knees, wondering what to do. “Look down. Move your left hand a few inches to the right. Put your fingers closer together. And shift that left leg back a little farther.” I listened to his instructions and the way he talked to himself as he buzzed around the camera, making sure everything was set and in order. “Michael, don’t lose this shot. Put this on eleven. No ten. Change the light. Catch that shadow. Get her feet in frame,” he mumbled to himself. And then he said, “Final focus.” From the corner of my eye I caught him inserting a large black cartridge (film for his art) in the camera before he took a snap. We did a similar version of the same pose. And two others. The whole thing lasted thirty minutes, during which time he made not a single comment about anything other than the fact that the shots would be gorgeous. I didn’t even have time to feel all of my neuroses about being undressed in front of a man I didn’t really know.

The short moments of being there, however, were great for my (often fragile) ego. “Beautiful. Great. Just like that. Oh, my God, that’s amazing and gorgeous,” he’d say as he looked into his lens (which he had to do while standing on a chair and flipping his head upside down because the camera inverts the image).

Soon after, he sent me on my way. “That’s it?” I asked. “Shouldn’t I do more?”

He apparently got everything he needed. I walked away, thinking,

I knew it! I knew it! I knew I would be a bad model.

I thought for sure I was a failure. Hours later he called me, freaking out, screaming into the phone, “You have to come to the studio right now and see this. It’s so hot. I can’t believe how hot it is. I mean, I can’t even take it. If an artist is only as good as his last piece, then I’m fucking amazing,” he yelled into the phone.

“It’s good?” I asked sheepishly.

“It’s ridiculous! It’s the best work I’ve done,” he said.

I threw on my Uggs and hopped in a taxi to head to the studio. I had to see. I was petrified, though, that I’d take one look and want to hurl. I am my own worst critic. I am the type who looks in the mirror and sees the zits or blemishes before anything else. I would gladly tell you everything that I haven’t accomplished over what I have. And while I was in Michael’s studio, staring at the eight-by-ten negative, looking at my figure, I didn’t see a trace of stretch marks, the thighs I don’t like, and the tummy I wish were flatter. You can’t really make out any part of my body or my face, which are colored by his painting in oranges, blues, yellows, greens, and another one with graphic lines that are kind of sixties mod.

I wasn’t sure whether to laugh or cry. There I was—a piece of art. The composition was so magnificent, I couldn’t believe that he caught that with just a few snaps of the camera. I was the girl who looked so languid and curvaceous at once. “I knew you’d be perfect,” he told me. “We just made some serious art together.” It was an overwhelmingly powerful moment. Tears streamed down my face. I was touched that someone saw this kind of beauty in my energy and captured it on film . . . where it remains forever without a hint of fear that it will someday feel dated, old, or out of style.

That’s the beauty of art. It lasts a lifetime and gets better with age. And having the piece (Michael actually gave me a blowup, which now hangs in my boyfriend’s apartment) is a constant reminder that some things are greater than fashion.

MODERN-ART DARLINGS TO CASUALLY NAME-DROP

Matthew Barney. Not only is he Björk’s husband (can you imagine what hanging out with them would be like?), but he is perhaps one of the most important contemporary artists. His media are painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, and film, which he morphs together in an offbeat and unconventional fashion. His installation “Cremaster Cycle” (1994–2002), named after the muscle of a man’s body that flexes upon ejaculation, is an epic, dreamy, surreal, complex work consisting of five 35mm films rife with anatomical, sexually reproductive allusions, building construction,

color, murder, dentistry (!), nineteenth-century Budapest, metaphors of birth, death, and the cycles of nature, not to mention a mosh pit or two.

Sometimes the best art requires no fashion at all.

Cecily Brown. A British glamour-girl painter who shows at the Gagosian Gallery (the Gucci of galleries) and is known for semiabstract, often erotic, wildly colorful paintings that focus on narcissism and human bodies. She often gets more attention for her hotness than her art, and the truth is, she is hot, but her art is hotter.

Sophie Matisse. The great granddaughter of Henri Matisse and the stepgranddaughter of Marcel Duchamp; her work is surreal and vivid. It must run in the family.

Damian Hirst. A British bad-boy shock-art prodigy whose body of work includes pickled sheep, an installation of a pharmacy with stuff on the floor, a wall hanging with meticulously placed pills, a shark in a tank of formaldehyde, dissected animals. A janitor actually threw away a large part of one of his exhibits while cleaning because he thought it was garbage. He also has remarkably cool works that look like those splatter-paint things you spun in circles and played with as a child. He was once spotted in a drunken stupor, stealing furniture from the Soho Grand Hotel—it was plastered all over the gossip columns.

Michael COLAVITO Hoiland. Yes, that’s how he spells his name. He likes to capitalize on the Colavito part. Maybe because it sounds so Italian and arty. His art is a modern blend of exotic photography and serious paintings that are reminiscent of old masters of the postimpressionist period, in addition to sculptures, geometric linear creations made with wire and glass, and wild fluorescent light infusions that he blends with his photographs, as well.

Anyone emerging from the Saatchi Gallery in London, a forty-thousand-square-foot space dedicated to promoting young British contemporary artists. Run by advertising mogul Charles Saatchi, who got a lot of heat for showcasing an artist who put elephant dung on a painting of the Virgin Mary in a much-talked-about exhibit called “Sensations.”

Anyone you like who really affects you. There are no rules as to what’s right and wrong in art. Just trust your taste. Claim it’s all chic, postmodern, ironic, and pre-Memphis and you’ll be fine!

Note: Architects are also a good source of conversation. Admire buildings, modern homes, and sculptures, and consider learning about midcentury icon Richard Neutra, known for his simple, clean “case study” homes (Tom Ford owns a Neutra house), in addition to Richard Meier, one of the premier architects of today and the man behind the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, many trendy restaurants, and two sky-rises in Manhattan where Nicole Kidman, Calvin Klein, and Martha Stewart have all bought.