The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 (9 page)

Read The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General

By 1870 it could with justice be said that France had become one of the most truly democratic parliamentary monarchies among the major powers; there was more liberty than under Louis-Philippe, the Press and political life were as unrestrained as during the Second

Republic. Yet the extreme Republicans continued to preach revolution and even assassination against the Emperor, regarding every fresh relaxation—the amnesty of the Republican exiles, the appointment of a former anti-Bonapartist, Ollivier, to take charge of the new ‘Liberal Empire’—as a sign of weakness. In a way they were right. Louis-Napoleon had been greatly debilitated by the deaths, in 1865, first of his shrewdest lieutenant, the Duc de Morny,

1

and later of Walewski and Troplong. There was little new blood available, and old tired faces seemed to surround him. Worst of all, about 1867 the Emperor himself began to show himself tired, worn out with the cares of governing, and foreign ambassadors noted how his conduct of affairs was becoming increasingly dilatory and infirm. At one point, von der Goltz reported to Bismarck that ‘the Emperor seemed to have lost his compass’. When Ollivier summoned up courage to tell him that people thought his faculties were declining, Louis-Napoleon (according to the Goncourts) replied impassively, and no doubt thinking of his private life, ‘That is consistent with all the reports I have received’. The truth was that the unhappy man was also beginning to suffer the tortures of the damned from an enormous stone on the bladder. Unable to sleep, he was forced to leave his retreat at St.-Cloud because of the noise of the clowns at a nearby fête, and the only sympathy he received from his subjects was: ‘What ingratitude on the part of the clowns, whom he had so protected throughout his reign!’

To an English observer who watched the young Prince Impérial drilling his troop of fellow boy cadets, Louis-Napoleon now ‘huddled in his seat, was a very minor show’, whereas the Empress struck ‘a splendid figure, straight as a dart, and to my young eyes the most beautiful thing I had ever seen…’, who ‘dominated the whole group’. As the powers of the Emperor declined, so those of his consort rose. In the eyes of her faithful admirer, Mérimée, ‘there is no longer an Eugénie, there is only an Empress. I complain and I admire…’. Others were less admiring. To them Eugénie—cold but capricious and unpredictable, adventurous and aggressive—was the single most disastrous influence upon the Emperor in his later years.

In 1869 the last of the great Tuileries masked balls was held; the Empress Eugénie appeared magnificently attired as Marie-Antoinette. As the menace from across the Rhine grew simultaneously with the Republican clamour at home, it seemed a remarkably ominous choice

of costume. About the same time, Lord Clarendon remarked to his Ambassador in Paris, Lord Lyons, ‘I have an instinct that they will drift into a Republic before another year is over.’ His guess was exactly five days out.

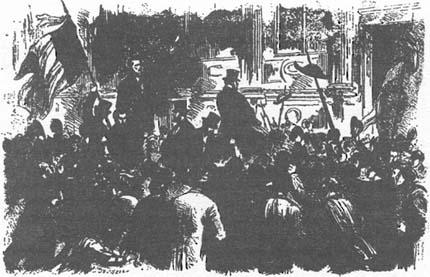

September 4th, 1870. Rochefort at the Hôtel de Ville

3. The Disastrous Six Weeks

N

OT

unlike that other year of catastrophe forty-four years later, 1870 arose wreathed in a warm smile of hope. In France, the ‘Liberal Empire’ which Louis-Napoleon had introduced under the ministry of Emile Ollivier at the end of the previous year seemed so full of promise that there was even a momentary upswing in the popularity of the Emperor. In a plebiscite held to approve the new Constitution (even though its terms, like those of most such referenda, were something of a swindle), the Government won an apparently striking success with a majority of nearly six million out of a total poll of nine million. Over Europe as a whole such a spring of content had not been seen for many years, so that by June the new British Foreign Secretary, Lord Granville, could justly claim not to discern ‘a cloud in the sky’. Peace was everywhere. But as summer developed it was a particularly trying one; in fact one of the hottest in memory. There were reports of drought from several parts of France, with the peasants praying for rain and the Army selling horses because of the shortage of fodder. It was just the kind of summer when tempers fray.

Then, at the beginning of July, a small cloud had passed across the

sun. To fill the vacant throne of Spain, Bismarck suddenly advanced a Hohenzollern candidate, Prince Leopold of Sigmaringen. So violent, however, was the alarm expressed in France at this threatened act of ‘encirclement’ that the candidate was promptly withdrawn. Relieved, Lord Granville chided the French Government for resorting to such strong language, and the

Illustrated London News

devoted its July 16th frontispiece to Queen Victoria dispensing prizes amid the peaceful surroundings of Windsor Park. Manet began to make plans for his holidays at Boulogne, and the clouds seemed to have evaporated. But the truth was that France, like a mass of plutonium, had reached the ‘critical’ stage. Ever since Sadowa she had not forgotten the apparent Prussian affront to her grandeur, and in 1868 one of her most intelligent men, Prévost-Paradol, had predicted that no French Government, however patient, could stand idly by while Prussia proceeded to unite Germany under her, without eventually ‘drawing her sword’. When dashing General Bourbaki of the Guard heard that the Prussians had climbed down over Spain, he hurled his sword down to the ground in disappointed rage. The country’s mood, that of a great power which sees its position of eminence being speedily eroded, was dangerous, and the Press, led by

Le Figaro

, now set to whipping up flames of bellicosity by inflammatory articles. After all the failures of Louis-Napoleon’s foreign policy in previous years, mounting pressure was applied upon the Government to seize this opportunity of pulling off, at any cost, a brilliant coup. Neither the Emperor (who still heard his cousin Prince Napoleon’s whispered warning that an unsuccessful war would mean the end of the dynasty) nor Ollivier actually wanted war. But the ailing ruler was being pushed hard, on one side by his heavy-handed Foreign Secretary, the Duc de Gramont, who has never forgiven Bismarck for calling him ‘the stupidest man in Europe’, and on the other side by his own Eugénie who, pointing to the Prince Impérial, declared, ‘this child will never reign unless we repair the misfortunes of Sadowa’.

Gramont now began to adopt towards Prussia a plaintive, hectoring tone. It was not enough that Prussia had retracted; she must be humbled for her presumption, and accordingly Gramont cabled his Ambassador in Prussia, Bénédetti, to keep the crisis hot. The King, who was taking the waters at Bad Ems, received Bénédetti on July 13th with the greatest courtesy. No one wanted war less than he; the unification of Germany he regarded as ‘the task of my grandson’, not his. But behind him was Bismarck, determined not to wait two generations, who had long since calculated that a war with France would provide the mortar he needed to cement together the present rather loose structure of the German federation. The pretext, however, had to be most carefully selected; one that would cast France

in the least favourable light, from the point of view of the other nations of Europe as well as that of Prussia’s own German allies. As he once remarked, ‘A statesman has not to make history, but if ever in the events around him he hears the sweep of the mantle of God, then he must jump up and catch at its hem’. With France showing herself determined to press for further diplomatic victories, to twist the knife in the wound, Bismarck thought he heard the sweep of the mantie. At Bad Ems, King Wilhelm had become irritated by the importuning of Bénédetti for a guarantee that the Hohenzollern candidature would never arise again. He declined to give such a guarantee, also refusing a request by the French Ambassador for a further audience. A telegram giving an account of his interview with Bénédetti was then despatched to Bismarck in Berlin; without actually fudging it, as he has frequently been accused of doing, Bismarck sharpened the tone of the dispatch before handing it to the Berlin Press and expediting it to every capital in Europe.

1

In fact, even with Bismarck’s editing, the famous Ems Telegram hardly seemed to contain a

casus belli

(certainly not according to the usage of modern diplomatic language, where the tone in which de Gaulle rejected Britain’s application to join the European Common Market in 1963 might be construed as only a shade less uncivil). But, although in the eyes of even French historians ‘never had an international cataclysm been unleashed over such a futile pretext’, the telegram was enough to entice Louis-Napoleon’s head into the noose. Throwing to the winds his favourite maxim of

Il ne faut rien brusquer

, he plunged France into perhaps the most

brusqué

action of her whole existence.

On July 15th France declared war. At once she found herself branded as a frivolous aggressor with neither friend nor ally. ‘The Liberal Empire goes to war on a mere point of etiquette’, declared the

Illustrated London News

. Austria had made it clear she would only join France in the event of a successful invasion of southern Germany. Italy would do nothing so long as there were French troops in Rome. Russia, where Tsar Alexander II was still annoyed at Louis-Napoleon’s encouragement of the Poles and further piqued by the apparently Insultingly light sentence passed on Berezowski, his would-be assassin at the Great Exhibition, was coldly neutral. The United States had not forgotten the Mexican adventure, and all hopes of British support were torpedoed on July 25th when Bismarck cunningly arranged for

The Times

to print the damning text of French proposals for a Franco-

Prussian partition of Belgium. Only the Irish, who had regarded Louis-Napoleon’s ‘Principle of Nationalities’s’ as being in their own interest, were on France’s side. Gladstone’s Britain, having declared herself neutral in 1866, had virtually relinquished any influence in European affairs; in any case she was preoccupied with domestic thoughts, so she too would remain, once again, strictly neutral; although sentiment was generally behind Carlyle when he contrasted ‘noble, patient, deep, pious and solid Germany’ with ‘vapouring, vainglorious, gesticulating, quarrelsome, restless and oversensitive France’. But few thought the ‘noble’ Prussians had much of a chance. On July 17th, Lady Amberley wrote to her mother indignantly, ‘It makes one miserable to think of that lovely Rhine a seat of war’, while Delane of

The Times

declared: ‘I would lay my last shilling on Casquette against Pumpernickel.’ Fortunately for Delane nobody accepted his wager, but it was not the last occasion when an editor of

The Times

would be wrong about Germany.

A young American woman, Lillie Moulton, who dined at the Palace of St.-Cloud on the eve of the declaration of war, noted: ‘The Emperor never uttered a word, the Empress sat with her eyes fixed on the Emperor and did not speak to a single person. No one spoke.’ But outside, in both nations, scenes of unparalleled exultation greeted the advent of war.

In Germany, where memories were invoked of the fourteen French invasions that had taken place between 1785 and 1813, the whole of Bonn University, a thousand students, joined the colours. In London, British bystanders gave a cheer to the trainloads of young Germans as they left Charing Cross on their way to join up, chanting ‘

Nach Paris!

’ In Paris something like hysteria reigned; mobs in the street sang the banned Marseillaise and shouted ‘

Vive la guerre!

’ endlessly, while the more erudite recited de Musset’s

Votre Rhin, Allemand

…

Où le Père a passé

,

Passera bien l’enfant

.

1

The Zouaves paraded a parrot that had been taught to screech ‘

À Berlin!

’

Le Figaro

opened a subscription fund to present every soldier in the Army with a glass of brandy and a cigar; and an enterprising publisher advertised a

French-German Dictionary for the Use of the French in Berlin.

On every hand, alleged Prussian ‘spies’ were seized and roughed up. For a very small minority in Paris, life continued

virtually unmarked by the outbreak of war; young Edwin Child was too preoccupied by the pursúit of an attractive compatriot called ‘Carry’, and Edmond Goncourt too distracted by grief at the recent death of his inseparable brother, for either even to note the event in their respective diaries. There were also a few dissentient voices. Flaubert wrote to his ‘dear master’, George Sand, ‘I am mortified with disgust at the stupidity of my countrymen…. Their wild enthusiasm prompted by no intelligent motive, makes me long to die, that I may be spared the sight of it…. Oh, why cannot I live among the Bedouin?’ From the very first, the war was markedly less popular in the provinces than in Paris, and Eugene Weber

1

tells us how the knocking out of front teeth was a regular self-mutilation resorted to, so as to avoid conscription (without them, it was impossible to tear open a musket cartridge), especially in the South West provinces farthest from Paris. From her country retreat in July 1870, George Sand also recorded the contrast between Paris ‘braying with enthusiasm’ and the provinces where the overwhelming feelings were ‘consternation and fear’.