The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 (5 page)

Read The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General

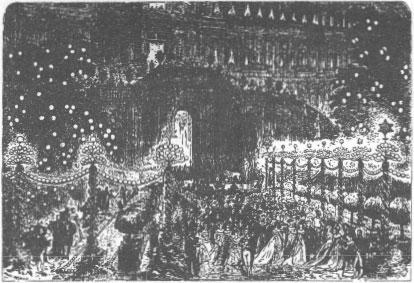

Few nights passed without one of the magnificent balls in which the Second Empire so excelled. At the great embassies they waltzed till dawn to the latest Strauss number, ‘The Blue Danube’. At the Tuileries, where the Empress gave a ball in honour of her Russian guests, and the great Strauss himself led the orchestra, the gardens had been rendered even more enchanting by cordons of that new invention, electric light, which made the extravagant uniforms and jewels so glitter and flash that once again

féerique

was the only word that sprang to mind. As red and green Bengal lights were reflected in it, water cascading over stucco rocks from specially constructed fountains ‘looked like a torrent of fiery lava

en miniature

’, wrote one guest. ‘No one thought of dancing. Everyone wanted to listen to the waltz. And how Strauss played it!’ Then the Emperor took to the floor with the Queen of Belgium, the Crown Prince of Prussia with the Empress.

When could this dream of a Thousand and One Nights ever end, what would replace it? But the climax of it all was to come with the great review at Longchamp. Again it was organized principally for the delight of the Tsar, yet Louis-Napoleon also had in mind how nothing impressed the King of Prussia more than a good parade, and

he was a man whom it was desperately important to impress. Sixty thousand troops were to have taken part—though, in the event, somehow only thirty-one thousand could be mustered. But in the vibrant sunshine, their sheer panache quite obscured such a numerical deficiency. From the great fortress of Mont-Valérien perched high above the racecourse, a cannon thundered out. The Emperor was arriving, escorted by Spahis on magnificent black chargers, and with the Tsar on his right and King Wilhelm of Prussia on his left. Led by the veteran Marshal Canrobert, the French troops marched and rode past their Emperor: grenadiers in high shakos, light infantry in yellow-striped tunics, chasseurs with green plumes, cavalry with their long lances and awe-inspiring helmets, fierce, turbaned zouaves in red and blue, accompanied by the little

vivandières

who skipped saucily along with small kegs of brandy slung, St. Bernard-like, round their necks. Then came the artillery, caparisoned as for a royal tournament, with superbly polished weapons that had seen service in the Crimea and at Solferino. To anyone who had inspected the Krupp monster on the Champ-de-Mars, the little brass cannon did seem somewhat antique; an observation not escaping the hard eyes of Bismarck, and which no doubt added savour to the private joke he had so enjoyed at

La Grande Duchesse

. But on this intoxicating June day these were ungrateful thoughts, drowned by the great roars of ‘

Vive l’ Empereur!

’ as each detachment swept past the Imperial stand. The review terminated with a massed cavalry charge of ten thousand cuirassiers, carabiniers, scouts, lancers, and hussars. Within five yards of the royal guests they halted, in perfect unison, saluting with drawn sabres. Amidst the wild applause of the spectators, the Tsar and the King of Prussia solemnly saluted their host, bowed to the Empress Eugénie, and then warmly congratulated Marshal Canrobert. It was, even the anti-Bonapartists had to admit, possibly the most memorable day of the reign. Nothing like it had ever been seen before—nor ever would again.

The Tsar, certainly, was impressed, and was almost effusive in the compliments he paid his host. Louis-Napoleon was delighted. The unattended new danger of Prussia in European affairs had dictated that his most important task during the Exhibition should be, in the unfortunate absence of Austria, to woo Tsar Alexander II, and the visit had not started off too auspiciously. There had been serious thought as to whether he should have come to Paris in the first place; it was after all the uncle of this new Emperor of the French who had caused the burning of his uncle’s Moscow, and memories of the Crimea were recent enough still to hurt. On his arrival a wide detour of the procession had been carefully planned by Louis-Napoleon, so

as to avoid the Boulevard Sébastopol; yet despite these precautions there had been shouts from the crowd of ‘Long live Poland!’, and the Tsar had reached the Tuileries in ill humour. But the seductive soft charms of Paris in early summer, the brilliant spectacles lavished upon him as well as the attentive courtesy of his host, had begun to thaw the Russian ice, and as they drove together from Longchamp, he had never seemed in better humour. Then suddenly something terrible happened. A twenty-two-year-old Polish patriot called Berezowski leaped out of the crowd and fired a pistol at the Tsar. He missed, but the white gloves of the Tsarevich were spotted with blood from a wounded horse. Louis-Napoleon was distraught; ‘Sir’, he said gallantly, ‘we have been under fire together; now we are brothers-in-arms.’ The Tsar, shaken by this all-too-nearly successful preview of the dreadful death fate was storing for him, was icy. In one second all Louis-Napoleon’s dreams for an accord with Russia seemed farther off than they had ever been.

There was talk of calling off the great ball to be held in the Tuileries that night. Somehow the shot fired at the Tsar had extinguished a portion of the blaze of light generated by the Exhibition. The police state once again revealed itself beneath the benign, almost liberal, countenance of the Empire. A heavy hand descended on ‘subversive elements’ in the Paris population, and even the ‘rebel’ artists were told that their private exhibitions outside the Champ-de-Mars would no longer be permitted. On June 11th a still outraged Tsar left Paris. Three days later the Prussian entourage followed, and the

Chefs de Protocole

stood at the station wondering if all the banalities of goodwill that had been uttered did not now ring a little hollow. As the lights dimmed, so people once more became aware of things standing in the dark shadows. Before long there was more bad news. On June 19th the Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico, Franz-Josef’s brother and Louis-Napoleon’s puppet, abandoned by his French protectors to the mercy of the Mexican nationalists, was shot at Querétaro. Ten days later the news was brought to Louis-Napoleon just as he was distributing prizes at the side of the Sultan of Turkey. This time all celebrations were at once cancelled, for with the death of the unhappy Maximilian died the hopes of the Bonapartes’ last foreign adventure. At top speed Manet produced a huge painting of the tragedy, but was forbidden to hang it in his gallery, on the grounds that it might be construed as reflecting upon imperial policy. Next there came reports that that old trouble-maker, Garibaldi, was on the move again in Italy, while in the Assembly the Orleanist, Thiers, was up to mischief. There were predictions of a bad harvest in France, portending a rise in food prices, and news from Algeria of cholera and famine.

Despite all this, the Exhibition with all its accompanying revelry carried on insouciantly throughout the summer and into the autumn. Towards the end, Emperor Franz-Josef of Austria paid a belated visit, though grieving a dead brother and with a sister-in-law driven insane by the tragedy, and too injured by France ever to offer either the friendship or alliance that Louis-Napoleon so badly needed. At the beginning of September Baudelaire, paralysed by syphilis, died aged forty-six in a madhouse; two months later workers began the dreary task of dismantling the Great Exhibition and a long line of Seine barges queued to remove the debris, the unrecognizable papier-mâché fragments of the gaudy pavilions and ephemeral kiosks. Soon the Champ-de-Mars was once again an empty field. With the departure of his last guests, Louis-Napoleon, as the shadows mounted round him once again, began to suffer pain from the stone for which the past excitement had acted as a distracting opiate. An atmosphere of after-the-ball-is-over descended on the city at large. Some sensed that the Exhibition had been the last rocket of the imperial fete, and that all there was left now was the smell of powder. Sober heads began to tot up the accounts. On the surface, there was no gainsaying the spectacular triumph of the Exhibition; even the Assistant Secretary at the American Legation, Wickham Hoffman, had to admit grudgingly that it was ‘the most successful ever held except our own at Philadelphia’. A staggering total of fifteen million people had visited it, three times as many as its predecessor in 1855. But had it done as much for the unemployed as it had for industrial progress? Would it bring France new prosperity at home, and above all had it brought her any new friends? Or had the foreigners who came simply departed more aware of France’s weaknesses and resentful at her triumphs? Certainly no one would challenge Comte Fleury’s famous remark, ‘In any case, we had a devilish good time’, which seemed to apply to the Exhibition as much as to the Second Empire as a whole. But there was also something in a nostalgic reflection made by Gautier as he mused on the Champ-de-Mars in sadder days three years later, when it seemed to him as if whole centuries had passed since 1867.

‘C’était trop beau!’

The Tuileries Ball, 1867

2. Empire in Decline

C’était trop beau!

T

HE

words may have been spoken in partial hindsight, but who during those

féerique

months of 1867, when the Empire seemed to have reached a peak of splendour, could have foreseen then what tragic reversal of fortune lay ahead for France, and particularly for Paris herself, within a passage of less than four years time? Who could have imagined that the scene of that glittering triumph, the Tuileries Ball, would be reduced to ashes, together with so much of central Paris; the Emperor disgraced and in exile; the Empire already little more than a dim memory? History knows of perhaps no more startling instance of what the Greek tragedians called

peripeteia

, the terrible fall from hubristic, prideful heights. Certainly no nation in modern times, so replete with apparent grandeur and opulent in material achievement, has ever been subjected to a worse humiliation in so short a time. Within just three years of the closing-down of the Great Exhibition, badly beaten French soldiers would be encamped upon the Champ-de-Mars;

la ville lumière

besieged by that amiable, courteous King of Prussia, her lights extinguished through lack of fuel, her epicurean populace reduced to a diet of rats. A few months

more, and that same king would be crowned emperor over the prostrate body of his former host’s fallen Empire; his coronation followed by one of the harshest peace settlements ever imposed by one European state upon another.

Who, in 1867, could have predicted all this? Yet there was still worse to come. Less than two months after the war against the Prussian invader had ended, and the first Siege of Paris had been lifted, there would occur in March 1871 the savage civil war for ever to be associated with the name of the

Commune de Paris

. Before this new conflict was over, during the last desperate days of May 1871 some twenty thousand men, women, and children would be massacred in the streets of Paris by their own countrymen; a blood-bath which made the Terror of 1793–4 with its twenty-five hundred executions protracted over fifteen months seem restrained by comparison, and which exceeded by far in numbers those killed by enemy action during the four months of Prussian siege. Out of the Commune’s brief revolutionary reign in Paris, and above all out of its brutal repression, would grow a deep-rooted bitterness that still gnaws at the heart of French politics today.

The Commune poses a set of problems rather different from those of the Siege. In order of importance, essentially military issues become replaced by social and ideological themes. Without the lessons and legends derived from the Commune, there would probably have been no successful Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, and its influence behind another French military disaster—that of 1940—cannot be obscured. In the light of all that has transpired since, the Commune appears as the more historically significant of the two events; certainly it is still regarded as such in the Communist world today. Even though the Siege and the Commune seemingly constitute two quite separate subjects, about each of which a flood of literature has been written, they should not in fact be treated in isolation. The Commune emerged directly from the Siege; without the Siege, the Commune of 1871 could never have happened; without an account of the Commune, the story of the Siege is incomplete. Many of the

dramatis personœ

are the same in both events, and, above all, Paris herself remains the grandly tragic heroine, common to each act.

And yet, however clearly the sparks which ignited the Commune may be traced to the Siege, there exist factors in the background, unconnected with the Siege, which contributed fundamentally to the explosive content of proletarian Paris. For an understanding of this, one has to turn back to examine the diseases concealed by the alluring façade of the Second Empire; as indeed one also must in order to find an explanation of why Louis-Napoleon’s Army which

had presented so brave and glittering a spectacle at the Great Exhibition should perform so dismally only three years later.

* * *

As memories of the Great Exhibition faded away and the Empire rushed on towards its extinction, in the three years of life remaining to it the sounds of revelry still lingered on, the masked balls continued. Just as in England the Victorian code became inseparable from the name of the sovereign, so from its very origins Second Empire society had never shown itself more loyal than in its eagerness to follow the paths indicated by its pleasure-loving Emperor. During the early days of the reign, the

haut monde

escaping from the bourgeois virtuousness of Louis-Philippe’s regime had sought consciously to recapture the paradise of Louis XV. In the Forest of Fontainebleau courtesans went hunting with their lovers, attired in the plumed hats and lace of that period. In Paris nothing set the tone of the epoch nor typified it more than those masked balls which so impassioned Louis-Napoleon, and at which he loved to appear as a Venetian noble of the seventeenth century. While the masks permitted their wearers to escape into a Walter Mitty world of fantasy, so the peacock extravagance of the occasions themselves bedazzled and distracted the eye from the more unpleasant realities that lay just beneath the surface. Each ball was more luxurious than the last, and throughout the reign those at the Tuileries occurred with such regularity as almost to resemble a non-stop carnival.