The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (3 page)

Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

FIG 2.4 FOUNTAINS ABBEY, YORKS:

The influence upon the village of monasteries was not only in their role as landlord but also in the clearance of woodland and even removal of whole settlements! The monks of Fountains Abbey were active in clearing land to create more profitable estates which at their peak stretched up into the Lake District, establishing granges from which their lands were farmed. Another influential group in the 12th and 13th centuries were the Knights Templars, in effect fighting monks established to protect crusaders, who managed their estates from preceptories. Local names and buildings which contain the word ‘grange’ or ‘temple’ may be linked to activities of medieval monks (‘grange’ was also commonly used by the Victorians)

.

The favourite pastime of many a medieval king was hunting and to preserve the deer and wild boars the Normans introduced Forest Law. This forbade poaching and prevented agricultural expansion into the protected areas but allowed deer to graze on the surrounding crops and huntsmen to trample over the fields in pursuit of their prey, much to the annoyance of local lord and peasant alike. The fines imposed for offences were a useful source of revenue for the Crown, so during the 12th century the area of land under Forest Law was expanded and by 1200 more than a fifth of England was affected (the area under Forest Law was often farmland and it is estimated that only a quarter of it was actually wooded). The lesser gentry also established deer parks, often large round enclosures where the animals could be housed before being released into the countryside for the hunt. By the 13th century, though, it was becoming financially beneficial for the king to charge a lord for permission to extend his fields into the wooded areas (assarting) instead, and to lose the income from the fines. Gradually the area under Forest Law was reduced although it was not completely abolished until 1660.

For generations we have been taught that this is the period when most of our villages were founded. Work by archaeologists and historians over the past 50 years has not changed this broad date but it has shown how surprisingly complex the establishment

and expansion was. We should remove from our minds images of Anglo-Saxon invaders surveying a deserted landscape after the Romans had gone, choosing at will a geographically suitable site and then naming their new village after themselves. As the previous chapter explained, the newcomers were fitting into an existing structure of estates and fields. Their first settlements were scattered affairs and until at least the 8th century farmsteads and hamlets were still dominant.

FIG 2.5:

Despite the popular assumption that incoming Saxons simply picked a spot and founded a village named after themselves, it is far more likely that the early settlers had to live on the scraps of land which were available outside of the existing estates

.

Villages in the form with which we are familiar today appear to have mainly taken shape quite late on, from the 10th to 13th centuries, and often when there was a change to the system of farming in the area. Although the church may have an earlier history or the name of a village may be found in records pre-dating this period of change, these factors only prove that there was settlement in the area at that time but not that it was in the form of a village. For example, our imaginary settlement in Fig 2.10 has a church to the left of centre, built by a Saxon thegn (a lesser nobleman) next to his hall from which he managed his surrounding estate, made up of isolated farmsteads. The name and boundary of his estate is recorded by charter and again later in the Domesday Book, but sometime in the 12th century the area has been reorganised and a new village laid out, with its name taken from that of the old estate. This is a simplified version of what you may find in many villages to be a more elaborate set of events.

Although the reasons for their establishment and development vary, it is likely that many villages in England have been at some stage fully or at least partly planned with more in common with Milton Keynes than the quaint meandering villages we are familiar with today! There are certain layouts with tell-tale signs of regular road and boundary patterns which have been identified, and it has been the later encroachment and the break-up of these divisions that have blurred the original planned form.

In the first case there were existing settlements which were extended or relaid out in this period. In a medieval village encircled by its own fields and wasteland used for grazing, there were limits to where new housing could be placed as the population grew. Any extension to the village or a re-planning of it would have to be agreed to, or initiated by, the lord of the manor. With only simple surveying techniques available, the new plots would have to be regular and rectilinear, with simple road patterns serving them. In other cases, villages would have been planned in a similar fashion but from scratch on a new site. This often happened where land was being reclaimed, as in the fens in East Anglia and other marshy areas which were beginning to be drained, or areas like Yorkshire which had been devastated by William the Conqueror’s ‘Harrying of the North’ and by raids from the Scots.

The motive behind many of these new planned villages was a commercial one by the respective lords of the manor. If they had been granted a plot of relatively useless land from which they could only expect low rents, it made more sense to put people on it who could farm the former wastes and dramatically increase their revenue.

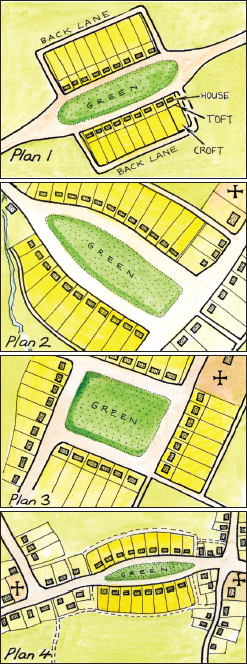

FIG 2.6 MEDIEVAL VILLAGE PLANS (

right

):

It is difficult to characterise all the possible layouts for planned villages but there are a few common patterns, shown here in their medieval form, which you may be able to recognise today. Plan 1 is a complete new village, plans 2 and 3 are additions onto one side of an existing settlement and plan 4 is linking two separate ends to form a complete village. It is worth noting how the crosses which mark the church and original focus of the village, are even at this early date being sidelined. The shift to new centres, in these cases around the greens and markets, demonstrates villages were not fixed in the landscape but moved to meet new opportunities

.

Another common financial venture was to try and establish a market in the village. Initially, this would cost the lord of the manor as he had to pay for a Royal Grant and then lay out a green area for the market and housing around it, but the potential profits to be gained from rents for the stalls and the plots was enough to outweigh this. It became especially popular in the late 12th and 13th centuries with the successful examples growing into towns, while perhaps the majority either failed at a later date or the grant

was never taken up in the first place. The site of a medieval market place and its regular planned plots can often be found under centuries of later developments.

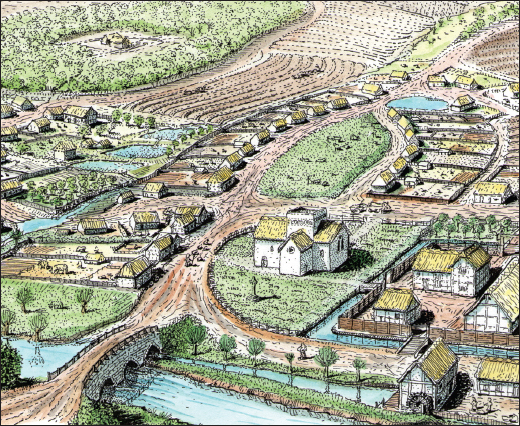

FIG 2.7:

An imaginary village in the 13th century with the manor house (within a moat) and the church next to it in the foreground. The earlier settlement developed in a haphazard manner in the left of this view but a new planned section has just been laid out in the centre background as an investment and site for a market. It is likely many villages had both these regular and organic elements to their form. Note also other common village features of this period, the mill (bottom right), fishponds (centre left), and a deer park (top left)

.

Many villages, however, were unplanned and expanded haphazardly, perhaps because the development was illegal or the lord of the manor let it grow in an unregulated manner. These could be linear settlements which grew alongside a road, a sprinkling of house plots based around an early industry like iron working, quarrying, or potteries, or a village on land carved out of woods or marshes. It will perhaps be found that the majority of villages grew with both planned and unplanned elements.

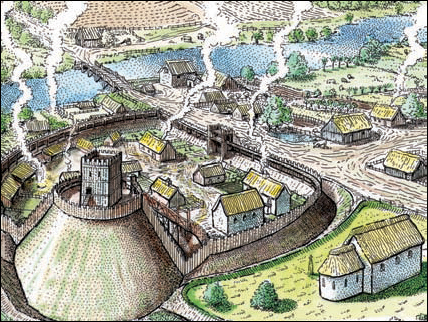

FIG 2.8:

In most medieval villages the church and manor house or castle were located close to each other as many of the former had been founded by the local lord (sometimes castle and churches were built at each end of a planned settlement). Motte and bailey castles as in this example often replaced earlier manor houses or defensive enclosures (see

Fig 1.1

which is the same view before the Conquest)

.

The arrival of the Vikings in the 9th century not only involved the robbing of the minsters and monasteries but also, as previously mentioned, led to the break-up of the old multiple estates into smaller holdings. These two factors seem to have weakened the power of the minsters, and during the following centuries a new network of smaller churches and parishes appeared.

Outdoing your neighbour was just as important to the ambitious Saxon landowner as it can be to some of us today. He had come into possession of one of these new small estates and desired the latest in status symbols by which the promotion to rank of thegn could be achieved, the answer to which was to build a church next to his own manor house. The lord of the manor though would have had no intention of paying for the upkeep of his new church. One of the reasons for building it was that the thegn could make a profit from his investment. The fact that his estate workers had a roof over their heads and did not have so far to walk in order to pray were probably minor considerations! The church would have had an endowment of land (a glebe) when founded, the income from which was intended for the support of the priest, who would be appointed by the lord of the manor, while the villagers also had to pay to bury someone in the churchyard. Although the old minster churches

would try to hang on to these valuable rights, the new lord of the manor would endeavour to have them transferred to his own church.

Further to this, in the 10th century the Saxon kings wrote the payment of tithes (a contribution of 10% of each villager’s produce for the upkeep of the church) into law. To determine which church this was paid to, parishes were established and, as most of the new churches were serving an estate rather than a village at this date, it was logical that their boundary would follow that of the estate. This means that where there have not been later recorded changes to the parish boundaries they can mark the limits of an old estate which may pre-date the village upon which it is now centred. The term ‘parish’ in this sense is an ecclesiastical area; in the north of the country, the secular equivalent was usually called a township or a vill, while in the south it could also be known as a tithing. A township, vill or tithing could follow the same boundary as the parish, or in some cases there may have been a number of them within one parish.