The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (9 page)

Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

FIG 5.10 EXEMPLAR VILLAGE c.2000:

Our imaginary village has now completed its journey up to the present day. The country house on the hill in the distance is now a business centre, but before its lord sold the estate he established tree plantations over much of it in an attempt to increase his income. To the right by the river the area around the mill has developed into an industrious village, leaving its original core isolated in the foreground. The church has been restored, with exposed stonework and Gothic details, while the manor house to its side is now a private house hidden behind trees and electric gates. Although at first glance the changes here are not as drastic as in previous periods, if you look closely, you can see evidence of the huge improvements to the standard of living for the villagers. Mains water, drainage and sewerage have brought hygiene and convenience, electricity powers heating and appliances, and tarmacked roads, pavements and street lights permit travel all year round

.

HAPTER

6

| The Landspace |  |

FIG 6.1:

The church, cottages and farms which make up this rural village only existed to service the landscape around it. To understand a settlement you must first look at its surroundings and this chapter explains some of the features you can see today which can help piece together its past

.

A

village is more than just bricks and mortar. Its reason for being, the changes which have taken place within it and often its demise can sometimes be identified by looking at the landscape in which it lies. The fields, woodland and parks provided employment and shaped the type and layout of settlement which supported them. In this chapter we look at these

features and the details you can see today which can tell us something about the past.

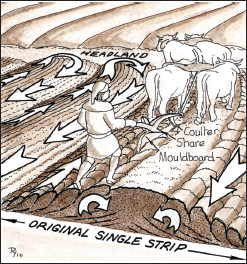

Ridge and furrow

The most easily recognisable remnants of the medieval open field system which you may be able to see around villages today are ridges and furrows. They were not formed to represent the individual strips, but are more a creation of the method used to plough it at the time. When working his long, thin strip the farmer would start in one direction with the mouldboard on the plough pushing the clods of mud inwards and then would repeat the process as he returned along the other side, which over a period of time caused the soil to build up into a low ridge. This may have been a deliberate policy, as some have suggested, to aid drainage, although the evidence for this logical theory is not always consistent.

FIG 6.2 ARLESCOTE, WARKS:

Best seen in low winter sunlight these ridges and furrows, distinctive features of medieval open field farming, can still be found where there has not been later ploughing and the fields were probably turned over to pasture as soon as they went out of use (note the distinctive reversed ‘S’-shape)

.

Another feature of ridge and furrow is the gentle curve or reverse ‘S’-shape they tend to form when looked upon from above. This is a result of the difficulty of moving the plough and the team of up to eight oxen onto the strip, which had to be done by turning them into it at an angle to avoid damaging the neighbour’s crop. Access to the strip was from the headland, which often developed into a substantial bank as the soil which fell off the ploughs built up over the centuries. Today it is possible to see the remains of these even where the ridges and furrows have been destroyed, or you might

notice a slight bump in a long ridge which reveals where a farmer bought out a strip on the other side of the headland and ploughed it over to link his holdings.

FIG 6.3:

A drawing showing how the ridges and furrows were formed by the turning in of soil as the plough went up and down the strip

.

When the fields around a village were later enclosed by agreement, the new holdings would be made up of a collection of the old strips, so the new boundaries which the farmers erected around them would mirror their distinctive reverse ‘S’-shape. The fields they created were often quite large, but could be later subdivided, so may contain straight hedges or fences within the patterns shaped by the earlier furlongs and strips. This could also occur when a farmer wanted to grow a different crop from the surrounding one in the open field. He could fence in his strip, leaving single thin fields within later regular ones.

The Parliamentary enclosures of the 18th and 19th centuries usually had grids of straight walls and hedgerows (usually of hawthorn or blackthorn) ruthlessly laid down by surveyors. Earlier ridge and furrows can often be found with these features laid across them. Farmhouses were built out in the middle of the new fields and the architectural dating of these within a parish may help you uncover roughly when the enclosure took place.

Inevitably the roads between the fields would have to change course within the parish being enclosed, which could mean when they reached the parish boundary they would have to be realigned to meet the old route in the neighbouring parish (see

Fig 4.4

). If you have ever gone down a country lane and found a sudden 90° turn one way, followed by another 90° turn the other then it might indicate where this has happened (it should be along the line of a parish boundary but this could be affected by later boundary changes).

One problem with rearing sheep is feeding them in winter and especially at lambing time in March. Water meadows beside a river or stream were managed with a thin layer of water directed over the field, protecting the grass from frost and permitting an early growth for the flocks to feed on. Drains, sluices and ridges alongside rivers and streams are remains which you may find today. Shallow dams can also be found in some small rivers and streams, sometimes remains of an old industry or a mill, in other cases they created shallow beds so cress could be grown, or were associated with trout fishing.

FIG 6.4:

Old ridge and furrow can show up on aerial photos or satellite images. These can also help identify older boundaries which fit in with the pattern of fields and later enclosure hedges which tend to cut straight over them

.

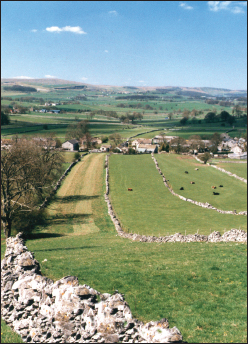

FIG 6.5:

Some older enclosures by agreement crystallised the former open strips, as here at Chelmorton in the Peak District

.

FIG 6.6:

In upland areas Parliamentary enclosure resulted in previously open lands being divided up by long straight lines of stone walling as seen here near Chelmorton in the Peak District

.

This was another important part of the medieval village landscape as timber was vital for building houses and erecting boundaries, such that the right to cut and collect wood was as tightly managed as the strips in the fields. The impression of dark, forbidding forests where the simple peasant would fear to tread is false. Most woodland up until the 19th century was managed, with the regular cropping and felling of trees creating gaps for light to flood in and flowers to grow.

Some trees like oak and elm would have been allowed to grow fully so their timber could be used for the major constructional parts of buildings. Others like hazel would have been coppiced, that is cut back to the stump every five to ten years to encourage thin, straight branches to grow, which were used for fence or house panels (the wattle in a timber-framed building). Hedges were also important, where a tree could grow larger than within a wood as there was no restriction of space.