The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (11 page)

Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

FIG 6.14 BIDDULPH GRANGE, STAFFS:

The Victorians loved trees and shrubs from around the world usually set on rocky or steep banks. If, today, you find evergreens of mixed variety and the dreaded rhododendrons, then this land was probably a 19th-century park or garden

.

The Victorians were more influenced by the picturesque, a love of rustic features, dramatic rocky landscapes, exotic buildings and imported conifers and shrubs like the rhododendron, which is now a major pest on many estates. With the decline in country estates in the 20th century many of the features which were once part of a scheme are left in isolation: fields with a scattering of large sycamore or oak trees, follies and towers left stranded on high ground or serpentine lakes in the middle of ploughed land. Remnants of these old gardens could be found around villages today.

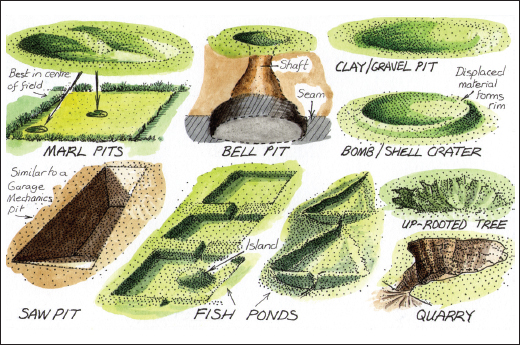

Road and river travel before the 19th century was too basic and slow for fresh sea fish to be transported to any but the coastal areas of England, so freshwater fish were often consumed. To keep a reliable supply the medieval lord of the manor or abbot would have fish ponds created, a set of regular shaped pools linked together and fed by a stream. The earthworks of these are still common features on the ground and, like the moats which they were sometimes linked to, can indicate the presence of an important house, castle or abbey.

FIG 6.15:

Impressions in the ground around a village can have distinctive forms which indicate what they formerly were. These examples (not to scale) may give you a clue to some of those you can find (marl is a clay or lime dug out as a fertiliser)

.

Many ponds and waterways were also created as a result of industry dating back to the Middle Ages. The extraction of salt for preserving food, stone for building, clay for bricks and peat for burning in areas where wood was scarce, resulted in pits being left which would often fill with water, creating small ponds or in the most notable case, the Norfolk Broads. In places where the soil was porous the empty pits would remain grassed over and a scattering of them around villages today is the sign of a long since vanished local industry. Lead and coal had been dug out or mined since Roman times and groups or lines of what are known as bell pits, the remains of the top of the shafts dug to reach the seams, can be found mainly on moors and within woods in mining districts.

FIG 6.16 BRILL, OXON:

The pits around this hilltop post mill are the remains of medieval workings. Ponds or small cliffs can indicate where clay or stone was extracted before the 18th century when large-scale operations were dominant. (Local names like Tylers Green or Kiln Cottage can help to confirm what was being extracted). It is also worth looking at parish boundaries. For instance if a number of them converge on a pond, then this records the shared right of all these parishes to allow livestock to drink here and probably means the feature predates the laying down of these boundaries. In this case, as in many others, the ponds and pits could have been formed naturally by erosion or the actions of the last ice age

.

Greens, to our modern minds, are an essential ingredient of the English village. These apparently ancient strips of common land are arenas for communal activities, fairs and sport and evoke great passions when their bounds are threatened. Yet the green we see today may only have been laid out in the 19th century for its ascetic value. The origins of a village green can be impossible to establish except in the cases where it was part of a planned extension, perhaps for a market or a completely new village. In other cases the village may have expanded to surround an existing piece of common land, with the settlement often given the name ‘End’ or ‘Green’, although the original village may have later contracted to leave just this isolated cluster of houses around it. Many villages never had a green and instead the churchyard was used for sports and fairs (until the 18th century when gravestones became common) and markets were even held within the church.

In most 19th-century planned estate

villages, the green was seen as a centrepiece by the creators of the romantic composition, while in industrial settlements it was set out with communal activities and sports in mind. In existing villages a new piece of land may have been purchased or granted to the parish, often rectangular and perhaps more of a sports field than a traditional green. Unfortunately, many ancient greens were not only built upon in past centuries but were lost or greatly reduced in size when the parish was enclosed. Old maps and road names can sometimes help identify where this has happened.

FIG 6.17:

Greens are a quintessential part of our ideal village and a venue for sports. This example at Great Badminton, Glos, like many, though, was created in the 19th century as part of the extension of an estate village

.

FIG 6.18:

Ancient greens at Askham, Cumbria (above) and Finchingfield, Essex (below). The buildings in the centre of the former example are later encroachments upon the originally longer green

.

HAPTER

7

| Transport |  |

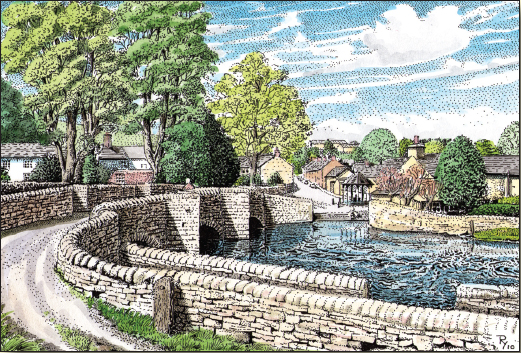

FIG 7.1 ASHFORD IN THE WATER, DERBYS:

The roads and bridges linking villages together and the rivers, canals and railways which brought them into contact with the outside world were vital in the formation and development of most settlements. They are also a focus for communities. The railway station or canal wharf drew people towards it while scenes like the above bridge are magnets today for tourists

.

J

ust as changes to agriculture, the extraction of mineral resources and the establishment of industry founded and shaped most villages, so developments in transport caused them to shift and expand. The poor quality and seasonal unreliability of the available transport methods remained

an issue until the 18th century when improvements to roads and rivers and then the arrival of canals and later railways aided the industrial revolution and caused those settlements nearby to move towards these new sources of trade and employment. The signs of where these shifts have occurred, the changes to routes over time and the structures directly built for transport can still be found in most villages today.

Ancient tracks

Wipe from your mind any thoughts that the people of this island before the Romans came were primitives with little ambition to escape their locality. There is plenty of evidence from as far back as the Neolithic period of trading over great distances: stone axes from the Langdales in the Lake District have been found as far away as Suffolk, while flints and pottery have also been discovered sometimes hundreds of miles from their source. It is best to imagine the routes these early traders would have trodden as wide, unenclosed strips of land rather than defined tracks and there is no direct evidence for where they ran. By the Iron Age we were trading with the Continent from ports like Hengistbury Head, near Bournemouth, where agricultural produce, minerals and slaves were exported in exchange for wine and exotic goods. We therefore had boats and carts to transport these and although the tracks were still unsophisticated there were bridges and raised walkways to cross watercourses, like the famous Sweet Track on the Somerset Levels.

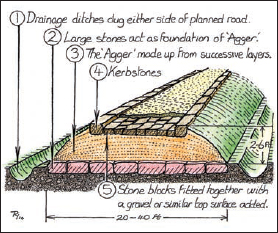

It was probably the presence of minerals and the agricultural surplus traded with the Continent which first attracted the Romans to our shores. They brought with them surveyors and engineers who built the familiar straight roads, the finest with ditches either side of a raised bank known as an agger and a cambered stone surface formed on top. These, however, were built with the military in mind and in between them there must have been a network of lesser tracks linking villas, hamlets and farmsteads to towns and

markets. We can be certain of the routes some of these main roads took from archaeological investigation, the presence of the Old English name ‘Straet’ (street) or ‘Port Way’, and from physical remains on the ground today. Do not assume, though, that any straight road is of this antiquity as the far more common 19th-century enclosure roads were also built straight with ditches either side (usually with hawthorn hedges alongside, unlike the route of a Roman road which you would expect to be less defined and lined with more mature and mixed species).

FIG 7.2:

A cut-away drawing showing how a major Roman road could have been made up. The low ridge of the agger is occasionally still visible today. The presence of a Roman road in a village is not proof that a settlement existed but could indicate that a villa estate, military fort or industrial workings may have been in the locality

.

Many Roman roads fell into disrepair after the departure of the last legions in AD 410, mainly because they did not link the new settlement pattern which developed in the Saxon period. With the collapse of the market system based upon Roman towns, a new localised network was established and only used those parts which were convenient. By the Middle Ages the lord of the manor would have been responsible for the upkeep of the main roads, but it is likely only the worst of ruts and potholes were ever repaired. New routes were rarely laid out except in cases of a planned village, a new manor house or castle, or realignment due to a change in river crossing. The local roads which took the peasant to a distant resource, neighbouring village or a market were usually just individual tracks between the new fields although older, more established ones were used in upland areas where the geology and an unchanging method of farming limited the choice of route between settlements and pasture. In these remote valleys, where a hamlet or village may have only had a chapel, the deceased had to be carried to the mother church for burial and the routes across the hills became well established, known today as corpse roads.

On the ground, older roads and tracks may be recognised by lengths which pass through holloways. These are cuttings formed by the constant use of the route, natural erosion and by farmers who in the past scraped off the dung and mud from the surface of the road to manure their fields. Another feature to look for is old hedges lining the sides of the road, which can often be recognised by the build-up of a bank from generations of growth and by the

presence of numerous species of plants within it (roughly one species equals 30 years of age, e.g. find ten species and the hedge could be 300 years old, but be cautious as this theory does not seem to work in all regions and can be misleading when dating a hedge which was formed by retaining a belt of existing woodland).

FIG 7.3:

Minor roads which run through narrow cuttings known as holloways, as seen here at Castle Combe, Wilts, may be older routes as the surface has been worn down through weathering and use rather than having been dug out in more recent times to lessen an incline (the road would normally be wider in these latter cases)

.

The increase in long-distance travel by officials, merchants and the gentry, as well as the transporting of goods and livestock by yeoman farmers, led by the 16th century to demands for improvements to the roads. Although the parish became responsible for the maintenance of the roads, their physical condition did not dramatically improve until the forming of turnpike trusts more than 100 years later. A group of local landlords would form a trust, then obtain a turnpike act from parliament which gave them the authority to take over and improve a stretch of road. When completed they would set up gates and toll houses and collect a fee from travellers for using their road, the money being split between future maintenance and profit for the investors (the word ‘turnpike’ comes from the spikes or ‘pikes’ which were fitted along the top of the ‘turning’ gates to stop horsemen jumping over them). Some landlords just did minimum maintenance and milked the money from tolls, others made major improvements, creating new roads which could have bypassed a village and thus affected its prosperity and caused it to migrate towards the trade which would be travelling along the highway.

FIG 7.4:

Polygonal-shaped, single- or two-storey toll houses like this one at Dorchester on Thames, Oxon, are still a common sight in villages and along roads today. Most date to the boom in road improvements from the mid to late 18th century and would have had a gate in front of them to stop traffic passing through without paying

.