The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (15 page)

Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

The churchyard can often be older than the building at its centre, formed when just a cross stood here at which a travelling priest from a minster church would preach to a converted Saxon congregation. Some which have a round plan may even be older than this. Throughout the medieval period, this hallowed ground would have appeared empty. There would have been few gravestones, perhaps some wooden crosses marking recent burials, and only a single large cross on the south side consecrating the land. In villages with no suitable open space the churchyard was often used for fairs and sports, and market stalls were even erected in the church itself! It was not until the late 17th century that stonemasons established themselves in villages and gravestones and tombs began to be raised for the better-off members of the community. They would try to be laid to rest inside, as near to the altar as possible, with wall plaques and stone ledgers in the floor overpowering some Georgian churches. If they could not afford this or the vicar was more strict then they would be outside, the wealthy in a chest tomb (the south and east sides of the chancel being the prized locations as they were nearest to the altar), the rest with just a gravestone, its size and decoration reflecting the wealth of the deceased. Most poor villagers, however, would have been buried with no permanent marker. It was not until mass-produced slabs and iron markers became available from the mid 19th century and burial societies were formed that the majority of villagers could afford to have a gravestone.

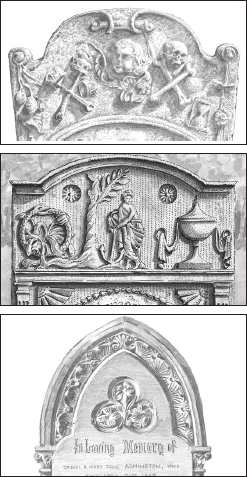

FIG 8.15:

The finest gravestones from the late 17th and 18th centuries have symbols of death and resurrection, like the skull, hourglass and angels (top). From the late 18th century the urn became dominant, sometimes with a scene of a weeping figure and a tree (centre). The cross only appeared on gravestones in the Victorian period either as the memorial itself or as an emblem on the slab which is often formed into a pointed arch (bottom). Most gravestones were for the better-off members of the community; the labouring poor may not have been able to afford one

.

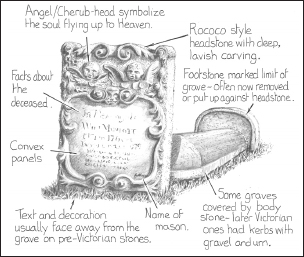

FIG 8.16:

Most graves before the Victorian period would have had a headstone with the text facing away from the burial and some a footstone at the lower end. Sometimes the grave between was covered by a body or coffin stone as in this example from the 1760s. It was only in the 19th century that the headstone was turned to look over the grave with kerbstones marking its boundary (old footstones can often be found today leaning against the headstone)

.

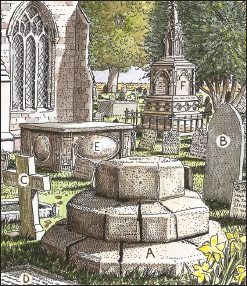

FIG 8.17:

The stepped base of an old medieval cross on the south side of the church often survives today (A) sometimes with a replica cross on top. The graves of the better-off were marked by a headstone (B), a cross in Victorian times (C) or a ledger (D). Tombs (E) and shrines (F) were reserved for the wealthy

.

Although often sited in towns or in remote locations, the remains of some medieval monasteries can be found next to present-day villages. The main church of the abbey or priory would have been the most substantial building on the site and it may survive as a partial ruin or could have been given to the parish after the dissolution and be still in use today (often in a truncated form as in Fig 3.6). This would have

formed the north side of a courtyard (cloisters), usually with a chapter house and dormitory down the east side, a refectory along the bottom and storage, guest accommodation and offices on the west. Even where there are no remains of the main buildings today, old gate-houses which would have stood across the entrance to the site and small churches built outside the enclosure to serve the village can often be found.

The invading Normans had to establish a firm grip on their potentially rebellious Saxon subjects so they built castles towering over their timber and mud hovels. They were positioned to control strategic or important places and were usually set on a prominent point overlooking the location or if this was not possible had a mound or motte raised. In some cases these seem to have been built on the site of a previously fortified Saxon residence, so it could be argued that William the Conqueror brought with him a new style of construction rather than a radically new invention.

To ensure his barons did not become too powerful, the king made them apply for a royal licence in order to build their own castles. This system collapsed in the 12th century during the civil war of King Stephen’s reign, which led to another spate of building, this time by the local lords who were free to erect their own makeshift castles, although these were often pulled down when order was restored under Henry II. If it is located near a river crossing,

at the head of a valley or some other important military position then a castle may date back to the Conquest. If the position seems less strategic then it may have been erected by a local baron between 1136 and 1154.

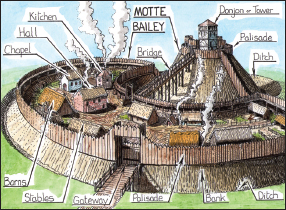

FIG 8.18:

The most distinctive early type of castle was a motte and bailey where a mound (the motte) was built up in layers and a timber tower (the keep) erected on top. Below this to one side a large enclosure (the bailey) was attached within which was the garrison, sleeping quarters, stables and workshops, while the whole site was surrounded by a ditch (the moat) which was often left dry

.

FIG 8.19 YELDEN, BEDS:

The earthworks of a motte and bailey castle. The remains of these can be found all over England with rounded off mottes and a ring-shaped bank marking the bailey, but be careful as the raised earthen base of old windmills (mill mounds) or large round barrows can easily be mistaken for them

.

During the 1200s those castles which had survived the previous turbulent century were often updated in stone, with masonry keeps replacing the earlier timber ones (the motte may have been reduced in height or made obsolete due to the increased weight of the new buildings). Larger or extra baileys were often added with surrounding stone walls and a heavily guarded gateway, sometimes with additional fortification beyond it called a barbican. Castles from the late 13th century onwards often had round towers to reduce the threat of collapse, which could be caused by your enemy tunnelling under the corner of a square keep, and also to help deflect the impact of missiles from the latest siege machines. In this late medieval period, however, most new castles away from the border regions were usually residential, as it was fashionable to build imposing structures surrounded by a moat with a drawbridge to impress guests as much as to keep invaders or raiders at bay. You can often recognise these fortified houses by their less prominent position, the use of brick (in the east and south), and larger windows instead of a limited number of slits.

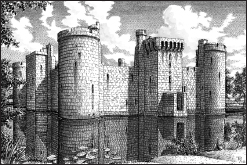

FIG 8.20 BODIAM CASTLE, SUSSEX:

Although castles were designed to control key areas and instill fear into the population, they were principally a home and as the threat against them diminished so they became lavished with fine halls and private chambers within their walls. By the 15th century some, like Bodiam, were built more as a fortified home than a military fort, its towers and moat more for show than serious defence

.

By the 16th century castles were viewed as obsolete and most had fallen into disrepair, only for some to be refortified

during the Civil War in the 1640s. In addition to using these old structures, extra defences or completely new forts were established, usually with a polygonal plan featuring spear-shaped protrusions; these distinctive forms can still found in fields today or show up in aerial photographs. Unfortunately the important military role the castles played led Cromwell and his army to render them unusable once the war was won, so much so that on many sites today only a few walls and their earthworks remain.