The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 (12 page)

Read The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 Online

Authors: John Darwin

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Modern, #General, #World, #Political Science, #Colonialism & Post-Colonialism, #British History

By the mid-1870s, a set of conjunctures and crises, scarcely imaginable some forty years earlier, had largely reshaped Britain's place in the world. More by default than by any design, they endowed Britain with the military, economic and demographic resources to sustain a world-system, given reasonable prudence. How that system was challenged, defended, reinvented and broken the chapters that follow are meant to explain.

2 THE OCTOPUS POWER

After 1870, the global conditions in which a British world-system had first taken shape began to change rapidly. Between then and 1900, the political and economic map of the world was redrawn. New imperial powers, including Germany, Italy, the United States and Japan, entered the stage; old ones ballooned in size. Africa, Southeast Asia and the Pacific were partitioned leaving only patches of local sovereignty: Ethiopia, Liberia, Siam. The great Eurasian empires of the Ottomans, Qajars and Ch’ing hovered on the brink of collapse: their division between rival predators seemed imminent and inevitable. The old political landscape of mid-century, with its separate spheres, was being fused into a single system of ‘world politics’. At the same time, industrialisation, the huge rise in the volume of trade, the wider reach of inland transport, the deepening penetration of capital, the tidal wave of European migration and the lesser flows of Asian, were creating a global economy in which even basic foodstuffs were ruled by a world market and world prices.

1

In this more intensely competitive setting, hitherto ‘remote’ societies were brusquely driven to ‘reform’. In many, the hope of building a new model state to beat off outsiders and suppress internal revolt, was forlorn at best and ended in crisis and colonial subjection. Meanwhile, in those societies already under colonial rule, or where European influence was being felt more acutely, political and cultural resistance came to seem much more urgent, and the appeal of ‘nationalism’ (in various forms) began to rise sharply. Even at home, or among overseas British communities, new kinds of mass politics reflected the sense of ever deeper exposure to external forces, and the need to create greater social cohesion by reform or exclusion.

An early source of alarm was a Near Eastern crisis that threatened to bring Russian power to the Straits (and thus the Mediterranean)

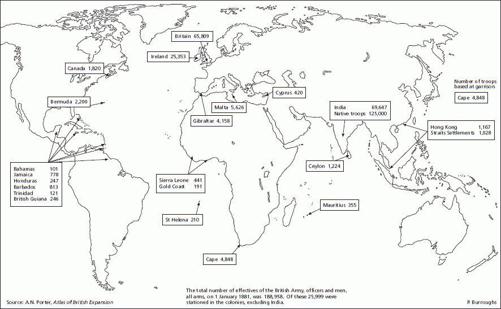

Map 3 Distribution of British troops, 1881

and make the Ottoman Empire a client state of the Tsar. It was rapidly followed by a general crisis in Egypt, and by a British invasion intended, said London, to restore order in Cairo before an early withdrawal. There was no withdrawal. Instead, within less than three years the British became party to an extraordinary plan for the territorial partition of Africa. Under the rubric of ‘effective occupation’, a bundle of treaties made with African rulers would justify a protectorate or even a colony. Whether intended or not, the result was a ‘scramble’, and the rush to partition was echoed in other parts of the world. But what had led British governments to react in this fashion? What risks did they run? How would opinion in Britain respond to the mass of new liabilities that scrambling imposed? Would it relish the triumphs that ‘new imperialism’ brought home, or remain sourly indifferent to these baubles of empire? Was this burst of expansion a sign of irrepressible confidence in Britain's ‘manifest destiny’ or the gloomy precaution of a power in decline and its hag-ridden leaders? Had British greed wrecked their diplomatic position in Europe and united their rivals in shared animosity? Some people thought so. ‘We have not a friend in Europe’, wrote a cabinet minister as Britain plunged into war in South Africa, ‘and…the main cause of the dislike is…that we are like an octopus with gigantic feelers stretching out over the habitable world, constantly interrupting and preventing foreign nations from doing that which we in the past have done ourselves.’

2

The new geopolitics

Even in the 1870s, the alarm had been sounded about the speed with which the world was ‘filling up’. ‘The world is growing so small that every patch of territory begins to be looked upon as a stray farm is by a County magnate’, wrote the editor of

The Times

in 1874, in language he thought ministers might understand.

3

By the 1890s, the idea was becoming a commonplace. Frederick Jackson Turner (in an American context), and five widely influential writers, Charles Pearson (1893), Benjamin Kidd (1894), Alfred Mahan (1900), James Bryce (1902) and Halford Mackinder (1904) all regarded the closing of the settlement frontier and the demarcation of the world's land surface as the beginning of a new epoch.

4

Coupled with the growth of almost instantaneous communications, what the Canadian imperialist George Parkin called ‘a new nervous system’ of the cable and telegraph,

5

they had brought about a phase of unprecedented delicacy in great power diplomacy. ‘In the post-Columbian age’, declared Mackinder,

we shall again have to deal with a closed political system, and none the less it will be of world-wide scope. Every explosion of social forces, instead of being dissipated in a surrounding circuit of unknown space and barbaric chaos, will be sharply re-echoed from the far side of the globe and weak elements in the political and economic organism of the world will be shattered.

6

Mackinder's suggestion that the end of the open frontier of territorial expansion would have important effects upon domestic and international politics had already been anticipated by Pearson and Kidd. Now that the temperate lands had been filled up, argued Pearson, the pent-up force of surplus population would force governments in Europe to assume an ever larger role in social and economic life. Kidd believed that the closing of the temperate frontier of settlement had coincided with the arrival of a ‘new democracy’ in Europe, social as well as political, whose economic demands could only be satisfied by the exploitation of the tropics – ‘the richest region of the globe’.

7

Both writers assumed that only large, well-organised states could survive in an age of increasing competition for resources.

These large predictions also reflected powerful cultural and racial assumptions. Pearson, whose views had been shaped by the antipathy to Chinese immigration in the Australian colonies where much of his career was spent, imagined a future in which the ‘higher races’ would have been driven back upon ‘a portion of the temperate zone’.

8

He prophesied the rise of Afro-Asian states ‘no longer too weak for aggression’, with fleets in the European seas, attending international conferences and ‘welcomed as allies in the quarrels of the civilised world’.

9

No doubt his readers could feel their flesh creep as the ‘yellow peril’ grew closer. But to most writers it was the relentless pressure of Europeans upon other peoples and civilisations that seemed more obvious. The Anglo-Saxon, despite his humanitarian sentiments ‘has exterminated the less-developed peoples…even more effectively than other races’, remarked Kidd sarcastically.

10

Tropical peoples could offer no resistance to Europe's ‘absolute ascendency’. ‘Europe has annexed the rest of the earth’, remarked the historian-politician James Bryce, ‘and European ideas would prevail everywhere except China.’

11

The close contact between advanced and backward peoples marked a ‘crisis in the history of the world’.

12

Isolation was no longer an option: extinction or absorption was the fate of many tribes or peoples, and the ‘backward nations’ were condemned to be a proletariat. Nor was there any way of preventing Europeans from annexing and settling ‘countries inhabited by the coloured races’: the best that could be hoped for was to regulate relations between whites and blacks, Indians and Chinese to minimise friction and keep ‘some races…at the highest level of efficiency’.

13

To an acute observer of Indian civilisation, it seemed certain that the old cultural realm of Hindu polytheism was under siege from external forces, and that a ‘moral inter-regnum’ would intervene before the Hindu reformation was complete.

14

Lord Salisbury referred bluntly to ‘dying nations’.

It was hardly surprising that, among non-European writers, the irresistible advance of the Europeans was regarded with a mixture of awe at their technical prowess, and mistrust of their political motives. The overweening racial arrogance of Europeans was widely noted by Indian,

15

Chinese – ‘Westerners are very strict about races and they look upon other races as enemies’, said the influential mandarin-scholar K’ang Yu-Wei)

16

– and Afro-American observers. Europeans would make little progress in spreading Christianity in Africa, thought the highly educated black West Indian Edward Wilmot Blyden. They were hindered by climate but also by their supercilious view of African cultures.

17

Islamic intellectuals were divided between those who argued against any compromise with the subversive teachings of the West and those who insisted that a new synthesis could be found between its technical and scientific knowledge and a modernised Islam.

18

Underlying much of this academic commentary was the sense of an impending cultural struggle to reshape the non-European world. For the ruling elites of Afro-Asia's remaining independent states, international politics after 1880 were a race against time to achieve ‘self-strengthening’ before the might of the European powers imposed ‘protection’, annexation or partition upon them.

On all sides, world politics were coming to be seen as a vortex in which only the strong would survive, and then at the price of a discipline and organisation at variance with older traditions of diversity and individualism. Among Europeans, the sense of intensifying competition was sharpened by crucial changes on their own continent. After the 1870s, the brief experiment of free trade was swept away and, in almost every large power except Britain, agriculture protected and industry built up behind tariff walls. At the same time, the political geography of the continent was reshaped by the emergence of Germany and Italy as great powers and (after 1880) would-be colonial powers as well. The old triangular imperialism of Britain, France and Russia had become hexagonal. Since the European ‘dwarfs’ (as the Dutch described themselves) could not always be disregarded, imperial diplomacy sometimes became octagonal – even before the rise of American and Japanese power in the Pacific. Henceforward, it became hard to resist the claim that the principle of equitable compensation on which the peace of Europe was held to depend should be extended to any region where a European power had enlarged its possessions. For the British, the shock of change was particularly severe. British opinion had blithely assumed that, in the new world economy of rising trade and rapid transport, international free trade would guarantee their commercial ascendancy. Secondly, they had every reason to fear that their large, loose, decentralised confederacy, with its wide zones of informal influence and fluid primacy, would be especially vulnerable to a new imperialism of partition.

The intensifying pressure to modernise in a world more and more subject to a global economy and to a single system of international politics thus threatened a double revolution in which old (Afro-Asian) states would disappear and a new, more fiercely competitive group of (European) empires would emerge. Its first epicentre was in the Near East. The Ottoman Empire had been under siege since the 1770s but it had shown a remarkable capacity for survival. In the Crimean War, Russia, its main enemy, had been hurled out of the Black Sea. The empire had been cautiously ‘reformed’ to strengthen its army and centralising bureaucracy. But, in such proximity to Europe and with large Christian populations in its western provinces, this was bound to be difficult. Drawing closer to Europe through trade and technology risked upsetting the delicate balance of its internal politics. Borrowing heavily in the West to improve its rule was a gamble on economic forces over which it had no control. In 1875, disaster came. The Ottoman government declared itself bankrupt, defaulting on large loans in London and Paris. In the political turbulence that followed, reprisals against its Christian subjects (the ‘Bulgarian Horrors’) became a

cause célèbre

in Europe. Amid a wave of passionate sympathy for ‘fellow Slavs’, Russian intervention in 1877 led swiftly to full-scale invasion and the imposition of a treaty (at San Stefano outside Constantinople) which openly reduced Turkey to a client-state. With the loss of their European provinces (the richest part of their empire) and an indefensible frontier in Thrace, the Ottomans had reached the brink of final collapse. Russia's control over the Straits and her predominance in the Eastern Mediterranean – the nightmare of British diplomacy since the 1780s – was only a matter of time.

19