The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 (8 page)

Read The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 Online

Authors: John Darwin

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Modern, #General, #World, #Political Science, #Colonialism & Post-Colonialism, #British History

This furious commercial activity had created by mid-century a worldwide network of international business centred on Liverpool, Glasgow and, above all, London. The extension of trade brought with it shipping, insurance and banking, managed and financed by allied mercantile interests or by the merchants themselves. It built up a huge fund of ‘commercial intelligence’ – market information – and widened the circuits along which it travelled: business letters, reports, local chambers of commerce and globe-trotting businessmen. Since every market was different, there was no single objective and no unified lobby. The main merchant demands were protection from warfare or pirates – largely secured by Britain's command of the seas outside Europe; ‘free’ trade – meaning the right to trade in overseas markets on the same terms as locals; and ‘improvements’ – usually investment in canals, roads or railways. British exporters complained bitterly at the miserly spending of the East India Company's government on railways and roads, which they blamed for the shortage of return cargoes from India and the slow growth of their trade. The ‘Canadian’ interest grasped soon enough that Montreal's future depended on railways, if it was to survive the end of imperial preference in the late 1840s.

46

The British government's role in building the ‘commercial republic’ was not insignificant, but it was bound to be limited. As Palmerston claimed, it was keen to advance the sphere of free trade abroad. Through treaties of commerce, it sought to protect British merchants and their property from unfair or discriminatory treatment, and to obtain ‘most favoured nation’ status – the right for British goods to enter on terms at least as good as those enjoyed by the ‘most favoured’ foreign state. The treaty system and Britain's naval presence (the world's seas were divided into eight overseas ‘stations’) gave British merchants unprecedented freedom to trade, but no guarantee of success. ‘Free trade imperialism’, in the sense of intervention by London, largely functioned in this indirect mode. For five years in mid-century when a detailed count was kept, gunboats were sent to protect commercial interests

outside

the Empire in a bare handful of cases, usually against the threat of violent disorder.

47

But there were three important exceptions to this hands-off policy. First, government subsidy for the carriage of mail encouraged the rapid expansion of scheduled steamship services across the Atlantic, to South America and to India and the Far East. Secondly, as we have noticed already, the Navy maintained a flotilla of some twenty gunboats on the coast of West Africa. Palmerston declaimed on the need to use force there in the interests of trade. ‘Cudgels & Sabres & Carbines are necessary to keep quiet the ill-disposed People whose violence would render Trade insecure’, ran a vehement minute.

48

But of course the targets of Palmerston's cudgel were the slave traders who tried to drive out the ‘legitimate’ trade that threatened their own. The gunboats were meant to keep them at bay until the trade in palm oil and other commodities was strong enough to destroy them. Here was a case where commerce sub-served the great moral obsession of Victorian Britain. Thirdly, there was China.

China was much the most striking case where military power was used in the interests of trade. Under heavy pressure from the merchant lobby, and fearing a huge claim to compensate them for the opium that the Chinese had seized, London despatched an expeditionary force in 1840 to demand reparations and win commercial concessions. The treaty of Nanking in 1842 opened half a dozen ‘treaty-ports’ where British merchants were exempt from Chinese jurisdiction, laid down a maximum tariff that the Chinese could levy on imports and transferred the huge harbour at Hong Kong (then still a village) to the British. After the second opium war (1856–60), the list of ports was extended and the Chinese interior opened to foreign travel. To uphold these rights, the British maintained a fleet of between thirty and forty ships, most of them gunboats, to police the coasts and rivers against pirates, anti-foreign disturbances and uncooperative officials.

49

The commitment seems surprising since the volume of trade remained comparatively modest even late in the century – far below the levels of Britain's India trade. The answer may lie in a curious set of coincidences. Intervention took place at a moment of intense concern about British markets abroad and when the commercial promise of China was wildly inflated (a recurrent phenomenon for more than a century). ‘The nation who, but for the existence of certain restrictions on trade, would probably buy the greatest amount of English manufactured goods are…the Chinese’, claimed Edward Gibbon Wakefield in 1834.

50

Commercial access to China, as it turned out, could only be gained through the consular enclaves and extraterritorial rights to which Peking agreed, both of them subject to constant local attrition. It was India that provided the available means to secure British claims, and India that had a big interest in doing so. British trade in China was largely an outgrowth of the India trade: ‘East India’ merchants sent Indian opium and cotton to China to buy tea and silk. But the opium itself was a government monopoly, and the revenue from it made up nearly one-fifth of the Indian government's income. The amount exported to China rose astronomically in the 1840s and 1850s.

51

Here, profit and power were inextricably linked. Nor did it seem that the periodic coercion of China would be costly or difficult. When Lord Elgin was sent east in 1857 to demand a new treaty after the breakdown of relations at Canton, he was initially given a mere handful of troops and told to rely upon naval action (to cut the river above Canton and block the Grand Canal) to force Peking to terms. ‘It is not the intention of Her Majesty's Government to undertake any land operations in the interior of the country’, London grandly declared.

52

Migrants and missions

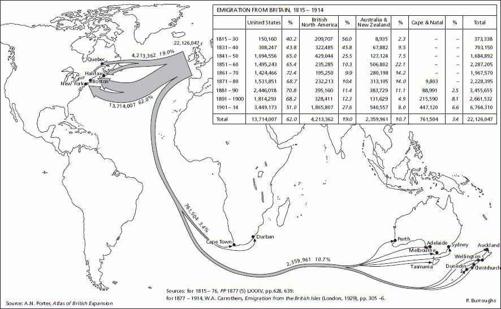

The search for new markets in the Outer World was the most obvious expression of British expansion. But it was allied to two others. The first was migration. After 1830, the number of migrants from Britain rose steadily: 1832 was the first year in which more than 100,000 departed for destinations beyond Europe.

53

The United States was much the most popular choice, especially for the huge outflow of Irish after the Famine. But British North America, Australia and (after 1840) New Zealand also attracted a significant number. Perhaps the commonest method was through ‘chain migration’ when an ‘advance party’ created the links (and perhaps remitted the means) to bring over friends and family.

54

But migration was also a business, and perhaps even a ‘craze’. Migration societies spread propaganda and fired enthusiasm.

55

The ‘idea’ of migration as a road to self-betterment became increasingly popular. There were also the land companies that sprang up in the 1820s and 1830s, to channel this movement and turn it into a profit. Their aim was to buy land (cheaply) from its indigenous owners (or a colonial government) and resell it (dearly) to settlers whom they recruited in Britain. The Swan River Settlement (in which Robert Peel's brother had an interest), the Australian Agricultural Company, the Van Diemen's Land Company, the Western Australian Company, the Canada Company and the British American Land Company were all of this type. The interest in such ventures was fuelled in part by social

Map 2 Migration from the British Isles, 1815–1914

anxiety. ‘Colonisation’ was a way of relieving economic distress, directly by removing unneeded labour, indirectly (as Edward Gibbon Wakefield argued) by creating new consumers abroad. It was no coincidence that some of the most ardent free traders (like Sir William Molesworth) were also drawn into the colonisation business. The South Australian Association was a highly successful lobby that won government support for a new settlement colony to which more than 10,000 migrants were sent in its first few years. Even more daring was Wakefield's New Zealand Association (1837), which successfully forced the British government's hand into annexing the islands.

56

Its patrons included some of the greatest and best, among them Lord Durham, cabinet minister, ambassador and the special commissioner into the Canadian rebellions of 1837–8. It promised, among other things, to save ‘the native inhabitants’ from the evils inflicted by the disreputable Europeans already in the country.

57

Not all were convinced. ‘This beautiful compound of the mercantile and the merciful’, sneered

The Times

, ‘will occasion a brisk demand for religious tracts and ball-cartridges.’

58

The colonisation movement, unofficial and private as well as organised and official (the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission was set up in 1840 mainly to subsidise migration to Australia from colonial land revenues), advanced in parallel with the great expansion of trade. It threw out dozens of settlements, often small and isolated, whose strongest links were with their parent communities in the British Isles, the source of their manpower, exiguous capital and religious identity. Tiny outposts, like those of the Scots on Cape Breton, lonely New Plymouth in New Zealand's North Island,

59

the even more lonely Kaipara,

60

as well as the larger and better known colonies in Upper Canada, New South Wales, Victoria, Otago and Canterbury, were all part of a web of human connections to which almost every part of the British Isles was linked. If commercial expansion helped breed a demand for ‘free’ trade, demographic expansion evoked a cry for ‘free’ land. The right of the British to settle abroad became as much part of their ‘birthright’ as the right to trade without let or hindrance. In the twenty-one years after 1850, an annual average of more than 200,000 people migrated abroad.

61

By that time, the idea of overseas settlement as amounting almost to a providential duty was becoming deeply entrenched. ‘The great object and purpose of England in colonising was the multiplication of her race’, declaimed W. E. Gladstone in 1852. ‘Whatever course of legislation tended most to the rapid expansion of population and power, in [Britain's] colonies, necessarily tended to enhance the reflected benefits that she was to derive from their foundation.’

62

There was a wide consensus in Britain, claimed Edward Cardwell thirteen years later, about ‘the great advantage of having these free, industrious and enterprising communities sharing their own blood, their own language, and their own laws, settled over the whole world’.

63

Migrant and mercantile interests could mobilise a wide if fragmented constituency to support the extension of British influence. So, for different reasons, could missionary societies. The most important of these were the Baptist Missionary Society, founded in 1792, the inter-denominational London Missionary Society (1795), the (Anglican) Church Missionary Society (1799), the British Foreign and Bible Society (1804) and the Wesleyan Missionary Society (1813). Launched on a wave of evangelical enthusiasm, the societies were carried by the surge of popular religiosity and the patriotic feeling of wartime. It was ‘artisans, petty shopkeepers and labourers who made up the bulk of the missionary workforce’.

64

‘Is it presumptuous’, asked the annual report of the Church Missionary Society in 1812, ‘to indulge the humble and pious hope that to Great Britain may be entrusted the high commission of making known the name of Jesus to the whole world?’

65

In 1813, in a signal victory, the societies forced the East India Company to fund a church establishment and admit missionaries freely to its territories on the sub-continent. By 1821, the societies had a collective income of over £250,000 a year.

66

By 1824, the Church Missionary Society alone had sent abroad more than 100 missionaries.

67

By 1848, it had over 100 stations and had recruited some 350 missionaries.

68

Between the 1820s and the 1840s, the missionary frontier was as dynamic as the mercantile. In South Africa, a survey between 1838 and 1840 counted eighty-five stations, most of them run by the London Missionary Society or the Wesleyans.

69

In New Zealand, where Samuel Marsden had arrived in 1814, well before annexation in 1840, more than sixty stations were active by the 1840s.

70

In the same decade, missionary enterprise in West Africa was carried along the coast from its old bridgehead in Sierra Leone to Yorubaland in modern Nigeria, where a station was founded at Abeokuta, and into the Niger delta at Calabar.

71

Johan Krapf landed at Zanzibar in January 1844 to open the campaign for souls in East Africa. By that time, the greatest prize of all seemed within reach. The first resident Protestant missionary in China had been Robert Morison, who was sent to Canton in 1807 by the London Missionary Society.

72

But the real missionary–king of the China coast was the anglicised German Karl (Charles) Gutzlaff. Gutzlaff had gone first to the Dutch East Indies where he made contact with Chinese traders whose junks still carried much of the commerce of Southeast Asia. In 1831, he made the hazardous journey up the China coast (then forbidden to European travellers) as far north as Tientsin, the port for Peking, and ingratiated himself with the local authorities by his medical skills. By the time he returned to Macao (to which European traders were required to withdraw at the end of the trading season in Canton), he had acquired a wider knowledge of contemporary China and Chinese than any other Westerner, and a brimming faith in the scope for conversion. His

Journal of Three Voyages along the Coast of China

(1834) was a sensation. A Gutzlaff Association was formed. It was Gutzlaff's ingenious formula of the medical missionary, and the glamour of bringing China to Christ that inspired the young David Livingstone: only the opium war and the temporary cessation of missionaries to China diverted him to Africa in 1841. But, with the treaty of Nanking in 1842, a new era had opened for missionaries as well as merchants: the following year, the Protestant mission organisations in East Asia met in Hong Kong to share the field between them.

73

The total of Chinese converts was tiny (six in 1842, 350 ten years later

74

); enthusiasm at home was to flag before it revived; and the missionary effort (as much American as British, Catholic as well as Protestant) was battered by the storms that swept over South and Central China in the 1850s. But it was missionary enterprise as much as commercial that defined the British presence in the Ch’ing empire.