The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 (14 page)

Read The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 Online

Authors: John Darwin

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Modern, #General, #World, #Political Science, #Colonialism & Post-Colonialism, #British History

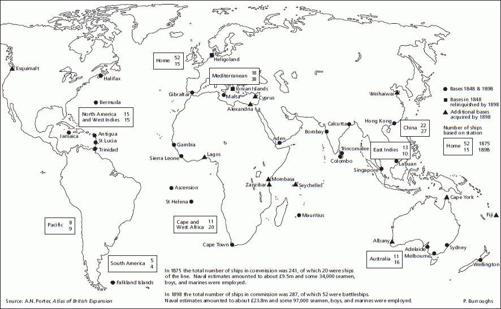

Map 4 The Royal Navy and its stations, 1875 and 1898

and the building programme of France. Between 1885 and 1890, the Royal Navy kept six first-class battleships in the Mediterranean. In the fretful 1890s, the number rose to ten and, by 1902, to fourteen.

37

The naval ‘scare’ became endemic and drove spending higher and higher: from £10.6 million in 1882 to £24 million by 1899. Even so, after 1893, fear of naval inferiority in the Mediterranean Sea was a governing factor in British policy. The sense of being dragged willy-nilly into a dangerous, expensive and inflexible commitment explains much of the continuing anger of the Gladstonians (until the mid-1890s) at what they regarded as the Egyptian folly.

Strategic insecurity placed a huge premium on diplomatic finesse. From the beginning, the British found themselves paying a diplomatic ransom for the occupation, and Egypt became, bizarrely, the fulcrum of their world policy. Having claimed a European mandate to reorganise Egypt's finances, the British were pressed by France and Germany (both with seats on the international

Caisse

which controlled part of Egypt's budget) to compensate the bondholders without delay. They pressed for wider international supervision of Egyptian finances, denounced the charge the British levied on Cairo for the cost of their garrison and threatened an international enquiry into the fiasco of the Sudan campaign. The British were to pay dearly for the privilege of staying. The result of this pressure was soon visible. To appease the Germans (who had less at stake financially), Gladstone referred a crop of colonial disputes to a congress in Berlin in 1884. There Bismarck wielded his

baton Egyptien

to good effect. To break the Franco-German combination and escape the general displeasure of Europe, the British abandoned a shoal of colonial claims. At a stroke, Bismarck gained an embryo empire in West, East and Southwest Africa and in the Pacific. To his lackey, the filibuster king of the Belgians, Leopold II, fell a giant crumb from the diplomats’ table: the Congo basin. The British took their reward in the easing of financial and diplomatic pressure on Egypt.

38

This was just the first round, for the partition of Africa, like the reform of Egypt, had hardly begun. The real task of managing Britain's ungainly new commitment fell to Lord Salisbury, the supremo of foreign policy between 1886 and 1892 and from 1895 to 1900 when he was both Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary. (He remained Prime Minister until 1902 but gave up the Foreign Office in 1900). Salisbury was greatly helped by the ruthless skill with which Evelyn Baring (later Lord Cromer) created a ‘veiled protectorate’ in Egypt to minimise open dissent. Baring's ‘system’ preserved the fiction of Egyptian autonomy. But it rested on the tacit knowledge of the Egyptian ruler that defiance would mean deposition; on the studied manipulation of Egypt's internal stresses; and on the systematic infiltration of the government by British ‘advisers’ who were Baring's eyes and ears. With unrivalled political intelligence, a British garrison (of 6,000 men), a reorganised local army under British officers, and an extraordinary hold over his political masters in London (a measure of their trust), Baring was able to restore Egypt's solvency (by 1890) and ride out the crises of his eccentric regime.

39

Salisbury's other advantage lay in the chronic mistrust between France and Germany and the gradual emergence of two rival diplomatic groupings: Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy on one side; France and Russia (after 1892) on the other. But he faced the constant risk that another crisis in the Near East might unite the continental powers behind a scheme of partition whose victim (apart from the Sultan) would be Britain's strategic link with India.

By outlook and training, Salisbury was well suited to this game of diplomatic poker. He took a disenchanted, ironic view of human motive. He mistrusted enthusiasm and laughed at nationalism (‘the philological law of nations’

40

). But he had thought deeply about statecraft and saw the virtue of an active policy in Europe.

41

‘Sleepless tact, immovable calmness and patience’

42

he deemed the secret of success; the diplomat's victories were ‘made up of a series of microscopic advantages….’ ‘Serene, impassive intelligence’ was the mark of the statesman.

43

Salisbury regarded foreign policy as a realm of technical expertise ill-suited to wayward cabinets let alone the rough and tumble of electoral politics.

44

He preferred to work in secrecy with a small group of aides. From his room in the Foreign Office or at Hatfield, his country house near London, he kept a close, obsessive watch on the cauldron of Near East diplomacy and the manoeuvres of his European counterparts. He held the threads of policy tightly in his grasp. In the ‘inner zone’ of British policy, the security corridor to India, his authority was not easily challenged. The ‘official’ interest in India and Egypt was under his command; occupation had soothed the Egyptian bondholders. Public hostility to Turkey aroused by new Armenian ‘Horrors’ was the main constraint. But, in the ‘outer zone’ beyond, where diplomacy grappled with unofficial colonialism, his grip was less sure.

Yet Salisbury's whole policy depended upon the careful balance between the needs of Egypt and the Near East, where Britain was most vulnerable, and British interests in other regions of the Outer World. In essence, his technique was to use the open spaces and ‘light soil’ of tropical Africa to appease France and Germany, soften their irritation at Britain's unwarranted primacy in Cairo and stave off an anti-British coalition among the continental powers. This was easier said than done. By the 1880s, unofficial or commercial interest in African hinterlands was growing rapidly. In Senegal and the Upper Niger, the military sub-imperialism of the French colonial army was on the march.

45

Rival groups of traders, missionaries and private imperialists were soon jostling each other and scrambling for ‘treaties’ granting commercial, mineral or religious rights. Worse still, they were remarkably deft at rallying public support at home for ventures easily repackaged as crusades against slavery or for the promotion of Christianity through commerce.

To Salisbury, the result seemed a nightmare of misguided if not fraudulent expansionism. At best it might be managed: it could not be suppressed. Left untended, it threatened to wreck the finger-tip delicacy with which he steered between the rival great power combinations. It might drive him into unwelcome friendships and towards unwanted confrontations. Many years before, ruminating on the sources of friction in European politics, he had argued that, when a state had become ‘permanently anarchical and defenceless’, its neighbours for self-preservation must impose a ‘tutelage of ambassadors…or…partition’.

46

This insight he now applied to anarchic, defenceless Africa. The aim of policy must be to damp down the quarrels of Europe's frontiersmen by an equitable partition of spheres before they could inflame opinion and damage the interests that really mattered. To this most detached observer of human foibles, with his gloomy view of the burdens on British power, it seemed obvious that the diplomatic defence of Egypt depended upon a cartographic fantasy: the parcelling-up of Africa.

Salisbury may have been the grand architect of African partition, applying his diplomatic method to regions as remote and unknown, he once said, as the ‘far side of the moon’. But he had to tread carefully round vociferous ‘interests’ at home, and ruthless empire-builders on the ground like Goldie and Rhodes. Without the means (and perhaps the confidence) to counter their mastery of the press, he took a fatalistic view of public opinion. ‘I once told Salisbury’, wrote the German ambassador, ‘that it seemed to be the Government's duty to lead public opinion. He replied that this was harder than I appeared to realise.’

47

Whatever his reservations about the methods and mentality of the private imperialists, he had little choice but to press on behalf of their claims. He mixed the careful palliation of Germany (exchanging Heligoland for Zanzibar) with the brutal coercion of Portugal (both in 1890). Portugal's claims in what is now Zimbabwe were dismissed with a growl – in favour of Rhodes. The contest with France, which had greater strength on the spot and, after 1892, an alliance with Russia, required much more finesse. Salisbury could not afford to let the French

officiers soudanais

and their ragtag black army hem in British interests on the West African coast and deny them their hinterland; or risk an armed struggle between them and Goldie's pale imitation of the East India Company (Salisbury was scornful of Goldie's Clive-like pretensions). Nor could he permit a French forward move into the southern Sudan, in case their arrival coincided with the expected collapse of the Mahdist regime in Khartoum. A French-ruled Sudan would have wrecked Cromer in Egypt. In the West African case, despite much bad-tempered diplomacy and some sabre-rattling in the bush, Salisbury largely achieved the partition he wanted. In the Sudan, his victory was much more complete. There Kitchener's (Anglo-Egyptian) army, with its light railways and steam launches, decisively smashed the Mahdist regime and captured Khartoum (in September 1898). With Marchand's tiny force at Fashoda hugely outnumbered, and the Royal Navy assembling in the English Channel, Paris abandoned its claim to the Upper Nile Valley.

Salisbury's triumph had been three-fold. He had secured Britain's position in Egypt, the strategic hinge of Anglo-Indian defence, without drawing down on his head a continental coalition. The price he had paid in African claims had been surprisingly light, guarding his flank against an outcry at home. Above all, he had avoided the diplomatic and military setbacks that dogged Disraeli and Gladstone and threatened electoral disaster. But, by the late 1890s, for all his success at Fashoda, it was no longer so clear that his deft combination of British strength on the ground, with an agile diplomacy and Britain's naval deterrent could protect British interests against the threat of attrition.

The main reason for this was the sudden emergence of a new epicentre of extra-European upheaval. China's shattering defeat by Japan in 1895 signalled a political bankruptcy as complete as that of the Ottomans twenty years before. The break-up of the Ch’ing empire seemed imminent. Even more alarming from the British point of view was the formation of the ‘Far Eastern Triplice’ – a coalition of Germany, France and Russia – to strip Japan of her spoils and impose their own terms for China's survival. Britain's commercial interests were centred on Shanghai and the Yangtse valley but spread out all over China. Neither Kwangtung in the south (the hinterland behind Hong Kong) nor North China and Peking could easily be given up. But with France looking north from Indochina, Russia south from the Amur, and German interest in Shantung, the British faced a squeeze and Salisbury a dilemma. He could fall in with an agreed partition and make the best terms he could. He could challenge the other powers to an open competition for the spheres and concessions which the Chinese offered in return for loans. Or he could hang back and wait, hoping the crisis would pass.

Salisbury's instinct was to wait. An early agreement with Britain isolated and the Triplice in harmony would be expensive and perhaps unacceptable to his colleagues and public opinion. An open competition risked extending the Triplice to the Near East, exposing the core of his system to the danger he tried most to avoid, and at a moment when the Armenian crisis and Anglo-French rivalry in Africa were coming to a head. ‘In Asia there is room for us all’, he soothed in November 1896.

48

But delay was not an easy option. Salisbury's caution was out of tune with the mounting excitement among the British in China and their sympathisers at home. The Asia-Pacific had replaced the Near East and tropical Africa as the platform for imperial publicists and commercial alarmists. The young George Curzon, patrician, politician, scholar, traveller and ‘coming man’, proclaimed the Far East to be the only region left where British manufacturers could find and keep an open market.

49

In the

Transformation of China

(1898), Archibald Colquhoun insisted that only in China could Britain hope to expand her Asian commerce and strengthen her position. The

Times

correspondent in China, George Morrison, regaled his foreign editor with dire warnings of French and Russian advance, while Chirol raged back against Salisbury's ‘infirmities’ and the ‘blundering and lying in which Downing Street excels’.

50

Inside the Cabinet, Joseph Chamberlain pressed for a more forceful policy:

51

outside it he intrigued for an ill-fated German alliance. Under this barrage, Salisbury moved crabwise. Peking was asked to promise that no territorial rights would be granted away in the Yangtse valley. Russian, French and German acquisitions were