The Crimes of Paris: A True Story of Murder, Theft, and Detection (42 page)

Read The Crimes of Paris: A True Story of Murder, Theft, and Detection Online

Authors: Dorothy Hoobler,Thomas Hoobler

Tags: #Mystery, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Art

Tragically, he would not be there to enjoy the acclaim. At the beginning of 1918, Apollinaire contracted pneumonia, which sent him back to the hospital, where he learned that the government had turned down his nomination for the Legion of Honor. Despite his status as a war hero (he had received the Croix de Guerre), the affair of the stolen statuettes, and the suspicion that he might have had something to do with the theft of the

Mona Lisa,

had not been forgotten.

He did not let the disappointment dampen his zest for love and work. He resumed his former acquaintance with a young, red-haired woman who was completely unconnected to the world of art. The final poem in his last book,

Caligrammes,

was about her

.

In May they were married in a parish church near his apartment on the Boulevard Saint-Germain. Still producing new work, he began to cough heavily in October. An influenza epidemic would kill millions worldwide during the next year, and Apollinaire was among its first victims. He died on November 9, and two days later, news arrived of the armistice that ended the war. As friends came to view his body, laid out on a bed in the newlyweds’ apartment, crowds thronged the streets, shouting

“À bas Guillaume!”

(“Down with William,” referring to the German emperor, Wilhelm II, who was forced to abdicate after the war).

iii

The years since the theft of the

Mona Lisa

had seen Picasso’s artistic reputation increase. Kahnweiler arranged for his work to be exhibited in Munich, Berlin, Cologne, Prague, and New York. In March 1914, a group of Parisian investor-collectors held a sale of contemporary paintings it had acquired over the previous ten years. The newspapers covered the event closely. A still life by Matisse brought 5,000 francs, quite a sum considering that works by Van Gogh and Gauguin went for less. But when a painting from Picasso’s rose period,

Family of Saltimbanques,

went under the hammer for 11,500 francs to a buyer from Munich, heads turned in the art world. Picasso would never know poverty again.

Picasso’s love life had thrived as well. He broke with Fernande in 1912 after she had an affair with an Italian painter, though some speculated that was a relief to Picasso, who was already in love with Marcelle Humbert, a circus performer whose real name was Eva Gouel. At about the same time, he began to paste objects such as chair caning and newspaper headlines directly onto the canvas, creating (along with Braque, who accompanied him in this as well as cubism) works known as collages. Increasingly those headlines reflected violence and the ominous approach of war.

After the war began, Braque, a Frenchman, joined the army, along with many others from the original

bande á Picasso.

Like Apollinaire, Braque was wounded in battle, and when he returned he was no longer as creative as he had been; he and Picasso never worked together again. Kahnweiler, a German, had to leave Paris for the duration of the war, making it difficult for Picasso to sell his work. Picasso’s mistress, Eva, had been in poor health for some time and died in December 1915. With most of his friends gone, Picasso now found intellectual stimulation only at the Stein apartment on the rue de Fleurus. Gertrude later wrote, “I very well remember at the beginning of the war being with Picasso on the Boulevard Raspail when the first camouflaged truck passed. It was at night, we had heard of camouflage but we had not yet seen it and Picasso, amazed, looked at it and then cried out, yes it is we who made it, that is cubism.”

13

Paul Poiret, the fashion designer and friend of Picasso, opened an art gallery on the rue d’Antin in 1916. Criticized because it seemed a frivolous thing to do during wartime, Poiret was defended in the newspaper

L’Intransigeant,

whose critic wrote, “Artists have to live, like other people, and France, more than any other nation, needs art.”

14

In need of money, Picasso remounted the rolled-up canvas of his controversial 1907 painting and let Poiret display it. For the first time, it appeared under the title

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,

a name Picasso is said to have disliked.

15

That same year, while designing the costumes and scenery for a production of Diaghilev’s

Ballets Russes,

Picasso met a ballerina named Olga Kokhlova, whom he would soon marry. In November 1918, Olga brought the news of Apollinaire’s death to Picasso as he was shaving. He put down his razor and began to draw the face he saw in the mirror. He was later to claim it was the last self-portrait he ever made.

16

iv

The carnage of the war, in which millions died for a cause no one could understand, left disillusionment and cynicism in its wake. Artists, or those who aspired to be artists, felt themselves unable to adequately express the emotions the unprecedented horror produced. George Grosz and John Heartfield,

17

two German artists, condemned the “cloud-wandering tendencies of so-called sacred art, whose adherents mused on cubes and gothic while the generals painted in blood.”

18

In the midst of the war, in the city of Geneva in the neutral nation of Switzerland, arose a new form, or theory, of art. Called Dada,

19

it was born at the Cabaret Voltaire, where refugees from other nations often gathered. The idea is generally said to have originated with Tristan Tzara, a Romanian poet, but many others contributed. Dada has been called “a nihilistic creed of disintegration, showing the meaninglessness of all western thought, art, morals, traditions.”

20

In short, it was a reaction against the civilization that had created the war. However, Dada artists made their point through black humor and absurdity. To them, art could be more—or less—than a drawing, a painting, a poem, a play; it might be something “created” at random or even an event where the actions of the participants, spontaneously generated, are the art. “Everything the artist spits is art,” declared Kurt Schwitters, one of the group.

21

The idea spread rapidly, for it appealed to those who felt that traditional art was inadequate in the face of the ultimate failure of civilization.

One of those who fell under Dada’s influence was Marcel Duchamp, a Frenchman from a family of artists. His cubist painting,

Nude Descending a Staircase,

had created a sensation at the 1913 New York Armory Show, the first major exhibition of modern art in the United States. Inspired by the spirit of Dada, Duchamp began to exhibit “readymades,” which were manufactured objects that he had transformed into art by either altering them slightly or simply giving them a title and declaring them art. One famous example was a urinal, turned upside down, that he signed “R. Mutt” and titled

Fountain.

In 1919, the four hundredth anniversary of Leonardo’s death, Duchamp took an ordinary postcard-sized reproduction of the

Mona Lisa

and drew a mustache and goatee on it. He wrote at the bottom his “title”: L.H.O.O.Q. With that alteration, Leonardo’s painting made the transition from a masterpiece of Renaissance art to an icon of modernism. Duchamp chose that particular painting to transform—or deface, if you like—because its theft had made it the most famous painting in the world, which it undoubtedly still is. The

Mona Lisa

was the biggest target Duchamp could aim at to show his contempt for what the old, prewar world had called “art.”

And the title? Pronounced in French, L.H.O.O.Q. sounds like

Elle a chaud au cul,

which is usually translated as “She has a hot ass.” And

that

is what La Gioconda is smiling about.

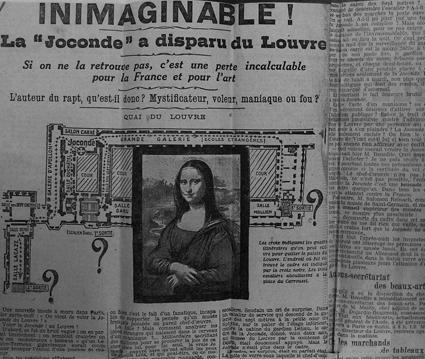

The

Mona Lisa,

one of the world’s most recognizable images. The French call her

La Joconde

and the Italians,

La Gioconda,

since the woman in the painting is considered to be Lisa Gherardini, who in 1495 married Francesco del Giocondo of Florence. Leonardo da Vinci began work on the portrait around 1503, when Lisa was twenty-four.

The sensational French newspapers of the day reflected the feelings of Parisians that the theft of the painting was an unimaginable crime. Headline writers struggled to describe its enormity.

(Paris Préfecture de Police museum)

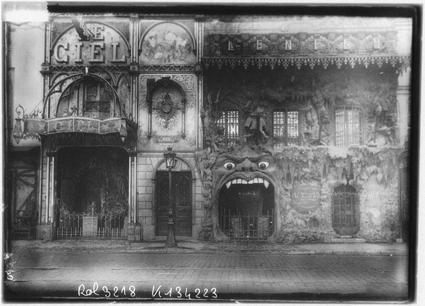

Next door to each other in Montmartre, the two cabarets of Le Ciel (Heaven) and L’Enfer (Hell) were elaborate theme restaurants where the waiters dressed as angels or devils and the irreverent entertainment poked fun at religious (or irreligious) practices.

(Bibliothèque nationale de France)

A journalist dubbed the young criminals who terrorized Paris in the early 1900s apaches. Edmond Locard, a criminologist, collected examples of their art, such as this clay depiction of a criminal about to face the guillotine.

(From the authors’ collection)

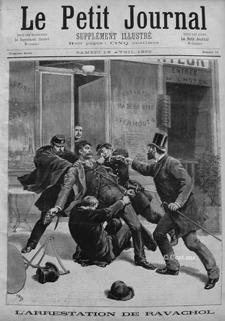

A newspaper artist depicted the police arresting the anarchist bomber Ravachol in 1892. A restaurant owner had recognized him from the description of Ravachol circulated by Alphonse Bertillon, who pioneered the science of criminal identification. On the way to jail, Ravachol struggled to break free, shouting to others in the street for help: “Follow me, brothers!

Vive l’anarchie! Vive la dynamite!

”

(Paris Préfecture de Police museum)

François-Eugène Vidocq was truly a larger-than-life figure. In real life a criminal imprisoned many times, he changed course to become the first head of the Sûreté, France’s equivalent of the FBI, and later set himself up as a private detective. He was the model for countless fictional criminals and detectives as well.

(From the authors’ collection)

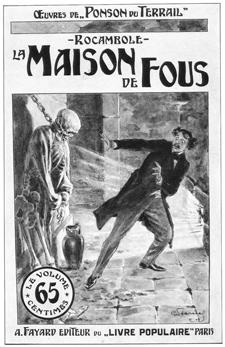

Pierre Ponson du Terrail was among the first to write novels that featured a criminal as the hero. Gino Starace, the cover artist for this later reprint of one of Ponson’s books, captured the ghoulish spirit that Parisians loved.

(From the authors’ collection)

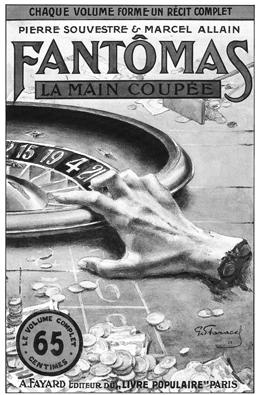

The ultimate French criminal “hero” was Fantômas, the creation of Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, who turned out a 400-page novel every month for nearly three years. Able to change his appearance almost at will, Fantômas committed countless acts of cruelty and violence, evading his hapless nemesis Inspector Juve in every one of the books, delighting readers.

(From the authors’ collection)

Pierre-François Lacenaire, depicted here killing an old woman in her bed while his accomplice finishes off her son in the next room, became as famous for his literary work as for his crimes. “To kill without remorse is the highest of pleasures,” he wrote. “It is impossible to destroy my hatred of mankind. This hatred is the product of a lifetime, the outcome of my every thought.”

(Paris Préfecture de Police museum)

Marie Lafarge was another criminal whose self-portrayal earned her notoriety; to many, she was a saint who had been unjustly accused. Despite Marie’s protestations of innocence, however, scientist Mathieu Orfila demonstrated conclusively that she had poisoned her husband. It was the first time that the science of toxicology had been used to convict a person of murder.

(From the authors’ collection)