The Crimes of Paris: A True Story of Murder, Theft, and Detection (45 page)

Read The Crimes of Paris: A True Story of Murder, Theft, and Detection Online

Authors: Dorothy Hoobler,Thomas Hoobler

Tags: #Mystery, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Art

When the

Mona Lisa

returned to the Louvre,

Le Petit Journal,

Paris’s most popular pictorial newspaper, devoted its front page to a history of the painting from Leonardo’s presentation of it to King François I to its theft from the museum.

(From the authors’ collection)

Alphonse Bertillon’s crime scene photographs, overhead and from the side, of the body of Adolphe Steinheil. Nearly two decades older than his beautiful wife, Meg, he had looked the other way while she engaged in a series of sexual liaisons, including one that reputedly killed Félix Faure, the president of France.

(Paris Préfecture de Police museum)

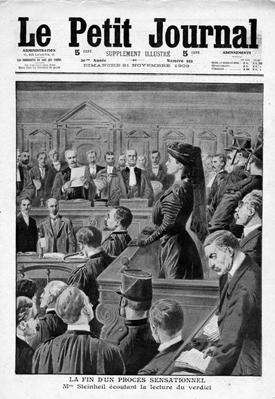

Meg Steinheil in the dock at her trial for murder. Her performance under questioning was so affecting that journalists dubbed her the “Sarah Bernhardt of the Assizes,” after the most famous actress of the day.

(From the authors’ collection)

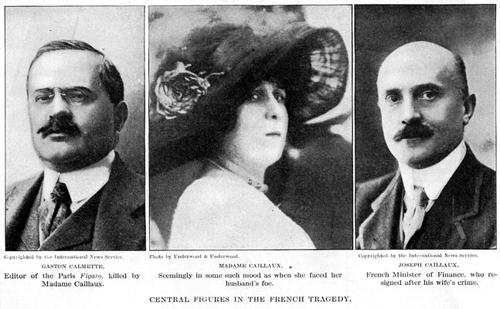

At left, Gaston Calmette, who was shot to death in his office on March 16, 1914, by Henriette Caillaux, center. At right is her husband, Joseph, at that time the finance minister of France, who had been the object of constant attacks by the newspaper Calmette edited. Henriette explained her action by saying, “There is no justice in France. There is only the revolver.”

(From the authors’ collection)

I

n 1932, the American reporter Karl Decker revealed what he said was the true story of the

Mona Lisa

theft. Decker was one of the most famous journalists of his time, not only reporting the news but making it as well. His best-known exploit occurred in 1897, when he went to Cuba, then under Spanish rule, and rescued the daughter of a Cuban rebel from jail. Decker smuggled her aboard a ship and brought her back to New York City, where his newspaper, the sensational Hearst-owned

New York Herald,

lionized both its reporter and the beautiful eighteen-year-old Cuban. The exploit was a prelude to the mysterious explosion that sank the American naval ship

Maine

in Havana Harbor the following year, setting off the Spanish-American War.

Thirty-five years later, in the

Saturday Evening Post,

at that time one of the United States’ leading weekly magazines, Decker claimed an even bigger scoop: that he knew who masterminded the theft of the

Mona Lisa.

In January 1914, while on assignment in Casablanca, Morocco, Decker had met a longtime acquaintance, a South American called Eduardo who had many aliases but was known to his associates as the Marqués de Valfierno — the “Marquis of the Vale of Hell.” He looked the part, wrote Decker: “His admiring associates declared that ‘his front was worth a million dollars.’ White mustache and imperial [goatee], and a leonine mass of waving white hair, gave Eduardo a distinction that would have taken him past any royal-palace gate in Europe without the troubling necessity of giving his name.”

1

Decker had crossed paths with Valfierno in a number of exotic places and had developed a friendship “based upon the fact that he was one of the few I have known who never bored me.” Decker had just returned from a three-month trip to the interior of Morocco and was unaware that a month before, the police had arrested Vincenzo Perugia and recovered the

Mona Lisa.

The marquis spoke of him as “that simp who helped us get the

Mona Lisa,

” and of course Decker’s curiosity was aroused.

2

Valfierno made the journalist promise not to publish the story until he gave permission or died. It was the latter event that allowed Decker to reveal what he had been told. Valfierno began by saying that the operation had been several years in the planning. He reminded Decker that in Buenos Aires, the marquis had made a small fortune selling fake artworks that his partner, a Frenchman named Yves Chaudron, turned out. Scanning the newspapers for obituaries of wealthy men, the distinguished-looking Valfierno would approach the widow to ask if she would like to donate a painting to her church as a memorial. At the time, Chaudron specialized in painting fake Murillos — skillfully imitating the seventeenth-century Spanish painter who was famous for his religious scenes — and these were passed off to the widows as genuine.

Valfierno felt that he was performing a civic service. “A forged painting so cleverly executed as to puzzle experts is as valuable an addition to the art wealth of the world as the original,” he said. “The aesthetic impression created is the same, and it is only the picture dealer, always a creature of commerce… who is really hurt when an imitation is discovered.… If the beauty be there in the picture, why cavil at the method by which it was obtained?”

3

The duo graduated from bilking widows to selling copies of Murillos that they claimed were stolen. Buyers were fooled into thinking that a genuine Murillo, hanging in a church or gallery, was in fact a fake placed there after the original had been filched.

Eventually, “filthy with money,” Valfierno and Chaudron felt that the game was getting old, and they sailed for Paris, where, Valfierno said, “Thousands of Corots, Millets, even Titians and Murillos, were being sold in the city every year, all of them fakes, but from my [point of view] this trade seemed cheap and unworthy.”

4

He added people to his organization, including an American who was well connected socially. This time, the marquis was more selective in choosing those he wished to fleece, concentrating on wealthy Americans — by nature, more gullible than Europeans — who could pay highly for “masterpieces” that had supposedly been stolen from the Louvre.

Unlike Géry Pieret, who actually stole the Iberian heads he sold to Picasso, the marquis and his gang “never took anything from the Louvre. We didn’t have to. We sold our cleverly executed copies, and… sent [the buyers] forged documents [that] told of the mysterious disappearance from the Louvre of some gem of painting or world-envied

objet d’art

.… The documents always stated that in order to avoid scandal a copy had been temporarily substituted by the museum authorities.”

5

Eventually, the marquis peddled the ultimate prize: the

Mona Lisa

itself, in June 1910. Not the genuine article, but a Chaudron-made copy, along with forged official papers that convinced the buyer (an American millionaire) that in order to cover the theft, Louvre officials had hung a copy in the Salon Carré. The buyer, unfortunately, was a little too free in bragging about his new acquisition, and that was why the newspaper

Le Cri de Paris

had printed its article — a year before the actual theft — stating that the

Mona Lisa

had been stolen.

Still, it had been a disturbing experience, one that the marquis was determined to avoid a second time: “The next trip, we decided, there must be no chance for recriminations. We would steal — -actually steal — the Louvre

Mona Lisa

and assure the buyer beyond any possibility of misunderstanding that the picture delivered to him was the true, the authentic original.”

6

Of course, he never intended to sell the real painting. “The original would be as awkward as a hot stove,” he told Decker. The plan would be to create a copy and ship it overseas before stealing the original. “The customs would pass it without a thought, copies being commonplace and the original still being in the Louvre.”

7

After the

Mona Lisa

had been stolen, the imitation could be taken out of storage overseas and sold to a buyer who was convinced he was getting the missing masterpiece.

“We began our selling campaign,” recalled Valfierno, “and the first deal went through so easily that the thought, ‘Why stop with one?’ naturally arose. There was no limit in theory to the fish we might hook. Actually, we stopped with six American millionaires. Six were as many as we could both land and keep hot.”

8

Chaudron then carefully produced the six copies, which were in due course sent to America and kept waiting for the proper time to be delivered. Valfierno said that an antique bed made of Italian walnut, “seasoned by time to the identical quality of that on which La Joconde was painted,” was broken up to provide the six panels that Chaudron painted on.

9

Now came what Valfierno thought was the easy part: “Stealing La Joconde was as simple as boiling an egg in a kitchenette,” he told Decker. “Our success depended upon one thing — the fact that a workman in a white blouse in the Louvre is as free from suspicion as an unlaid egg.… [It] was a uniform that gave [the thief] all the rights and privileges of the museum.”

10

Recruiting someone — Perugia — who had actually worked in the Louvre was helpful because he knew the secret rooms and staircases that employees used.

Perugia did not act alone, Valfierno said. He had two accomplices, needed to lift the painting and its heavy protective container and frame from the wall and carry it to a place where it could be removed. Valfierno did not name them, but anyone familiar with the case might have remembered the Lancelotti brothers, whom Perugia had briefly implicated in the heist when he was questioned in Florence.

The one hitch in the plan was that Perugia had failed to test beforehand the duplicate key Valfierno had made for the door at the bottom of the small staircase that Perugia used to make his escape. At the moment he needed it, the key failed to turn the lock. While he was removing the doorknob with a screwdriver, the trio heard footsteps from above, and Perugia’s two accomplices hid themselves. The plumber named Sauvet appeared and, seeing only one man in a white smock, had no reason to be suspicious. He opened the door and went on his way, soon followed by Perugia and the other two thieves. At the vestibule, luck was on their side again, for the guard stationed there had abandoned his post temporarily to get a bucket of water to clean the floor.

An automobile waited for the thieves and took them to Valfierno’s headquarters, where the gang celebrated “the most magnificent single theft in the history of the world.”

11

Now the six copies that had been sent to the United States could be delivered to the purchasers. Because each of the six collectors thought he was receiving stolen merchandise, he could not publicize his acquisition — or even complain should he suspect it wasn’t the genuine article. It was, indeed, the perfect crime.

“Chaudron almost died of joy and pride when he learned the prices his work had brought,” Valfierno said. “He… -retired to a country place near Paris and only occasionally does a piece of work for some really great worker in the field of fake-art salesmanship.”

12

Perugia was paid well for his part in the scheme — “enough to take care of him for the rest of his days if he had taken his good fortune with ordinary intelligence.” However, he squandered the money on the Riviera, possibly in casinos, and then, knowing where the real

Mona Lisa

was hidden, stole it a second time. The story that he carried it around in his trunk for two years was false. “The poor fool had some nutty notion of selling it,” Valfierno told Decker. “He had never realized that selling it, in the first place, was the real achievement, requiring an organization and a finesse that was a million miles beyond his capabilities.”

13

What about the copies? Decker wanted to know. Someday, speculated Valfierno, all of them would reappear. “Without those, there are already thirty Mona Lisas in the world. That in the Prado Museum is, if anything, superior to the one in the Louvre. Every now and then a new one pops up. I merely added to the gross total.”

14

Perhaps significantly, Decker chose not to publish this sensational story in one of the Hearst publications, even though he was still a Hearst employee. His boss, William Randolph Hearst, was a wealthy man who voraciously collected art — just the sort of person to whom Valfierno might have sold one of the fake

Mona Lisa

s. Hearst Castle, his fabled California estate, was donated to the state of California in 1957, and a curator there in 2005 reported that “there is not — and was not — a copy of Leonardo’s

Mona Lisa

at Hearst Castle,” although it was impossible to tell if one might have been part of “his larger collection located at various other venues, past and present.”

15

The Decker account is the sole source for the existence of Valfierno and this version of the theft of the

Mona Lisa.

There is no external confirmation for it. Yet it has frequently been assumed to be true by authors writing about the case. True or false? That mystery has yet to be solved.