The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment (25 page)

Read The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment Online

Authors: Chris Martenson

Tags: #General, #Economic Conditions, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Development, #Forecasting, #Sustainable Development, #Economic Development, #Economic Forecasting - United States, #United States, #Sustainable Development - United States, #Economic Forecasting, #United States - Economic Conditions - 2009

Oil Demand

As further confirmation of the importance of oil to our lives, we might look to the impact of the worst global economic slump in 70-plus years upon global oil demand. Where global trade plummeted by 20 percent to 40 percent in 2009 for most exporters, and where many individual countries have recorded high single-digit drops in GDP, we find that oil demand has not dropped by nearly as much.

In March of 2009, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated world oil demand for that year at “84.4 million barrels a day—1.5 percent lower than a year earlier.”

7

While a 1.5 percent drop is among the largest ever recorded, it’s a fraction of the decline recorded in other areas of economic consumption. Oil consumption is “sticky.” In the United States, petroleum consumption fell by only 4.1 percent from its peak in 2008 to 2010. Certainly this is a very large drop by historical standards for the United States, but it’s not all that drastic and leaves petroleum demand above where it was in 2003, indicating that oil consumption is perhaps a more essential feature of the economic landscape than many realize.

Or perhaps we could go further and say that oil is a nonnegotiable element of our lives. Where most of us can fairly easily and rapidly cut back on dining out or buying a new house or importing clothing, we cannot simply or quickly do the same thing with gasoline. It is quite difficult to pare back the number of miles driven to and from work or to school, for example, and such changes, if made at all, tend to happen quite slowly. This gives oil consumption its stickiness.

If oil demand is relatively robust and somewhat insensitive to economic difficulties, then what about oil production?

Oil Production

In November of 2008, the IEA released its World Energy Outlook (WEO) for 2008,

8

and in it produced the single most startling piece of information that I had yet seen on the subject of Peak Oil. In every prior year, the IEA provided an estimate of future oil availability that was generated after first consulting with economists about likely levels of global growth in GDP in future years. In other words, they modeled oil supply on the basis of what they thought the economy might require, not what could realistically be produced. In 2008, a new methodology was used. It incorporated all the world’s major oil fields, over 800 of them, into a single database, and then asked a very different question:

“How much oil

can

be produced?”

The answer, as it turned out, was a lot lower than any of the prior estimates. Where IEA estimates of oil production once topped out at 130 million barrels per day by 2030, the 2008 WEO report pegged that number at just 106 million barrels per day—a whopping 19 percent decline. Nearly 1 in 5 barrels of oil that were once thought would be available in 2030 suddenly vanished. Even more important, the report broke down oil supply by its various subcomponents, such as “conventional” and “deep water,” and revealed that oil from currently producing fields has been in decline since 2005.

Why is this statement a ground-shaking one? Because “oil from currently producing fields” is a euphemism for “cheap and easy oil” or “high net-energy oil”—the stuff that gives us the large gray territory on the bottom of the energy cliff graphs. With this stark admission that cheap and easy oil has already peaked, the IEA admitted that we’re already on the down slope of the same exact type of oil that has fueled the past several decades of economic growth. This earth-shattering news should have been on the front page of every major newspaper, but it wasn’t—we might ask ourselves why not—although it did circulate widely in the blogosphere.

Another revelation from report was that the bulk of all new oil-supply growth from here on out is going to come from fields “yet to be developed or discovered,” with some relatively minor contributions from “nonconventional oil,” which primarily refers to the tar sands of Canada and similar deposits. Neither of these sources can reasonably be expected to offer anything close to the same net energy returns of prior finds.

For example, extracting oil from the so-called “oil sands” of Canada has proven far more costly, capital-intensive, and environmentally destructive than first imagined. These were among the very first projects that were deferred, delayed, or dropped as a consequence of falling oil prices and diminished lending in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. I strongly suspect that the hoped-for contribution to supply from these sources will be adjusted downward in coming reports, possibly by a lot, due to a combination of poor financing and environmental concerns.

The final bombshell from the WEO 2008 report was the IEA’s estimation that the collective decline rate for all existing fields is now −6.7 percent annually. Here again, we’re faced with a mind-boggling admission. Using our handy rule of 70, but in reverse, a −6.7 percent rate of decline implies that existing fields will lose

half

of their output over a roughly 10-year timeframe. It should be noted here that the −6.7 percent decline rate averages together all of the fields, including the far healthier OPEC fields along with the stunning double-digit declines being recorded in some non-OPEC countries such as Mexico and Norway.

What this data tells us is that existing fields are collapsing far faster than was thought to be the case as recently as 2007. World expectations in this regard have been consistently lagging behind reality, and rather badly, too.

The Oil Production Output Gap

To add to this picture, not only are existing fields declining in output, they seem to be doing so at an ever-increasing rate, meaning that we have to run faster simply to stay in place. Some suggest the reason for this is that newer drilling methods and recovery techniques greatly increase the rate of extraction but not the amount that can finally be retrieved. It’s like squeezing the toothpaste tube a little harder—yes, it comes out faster, but you don’t create

more

. This is another example of where exponential declines can work against us.

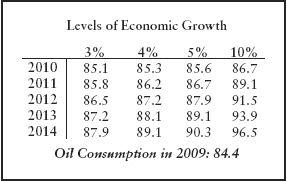

Recalling our oil-to-GDP ratio above, which yields a 0.27 percent increase in oil consumption for every 1 percent advance in global GDP, we can estimate required oil production levels under a number of scenarios. In the table below, we address this question:

Given various rates of global growth, how many millions of barrels of oil would we need to pump out of the ground each day to meet the desired rate of economic expansion?

Figure 16.8

indicates that even a historically modest 4 percent rate of global growth would require an advance from the 84.4 mbd (million barrels per day) in 2009 to 89.1 mbd by 2014, nearly 5 mbd in new, incremental capacity, or about 1 mbd each year. This is equivalent to roughly one-half of the entire output of Saudi Arabia.

Attempting the ludicrous, a 10 percent growth rate seen in the column to the far right (mirroring that seen between 2003 and 2007) would require that global oil production be expanded by 12 million barrels a day, or nearly one-and-a-half times Saudi Arabia’s 2009 output, over those five years.

Any of the above scenarios represent a significant gap between what we can currently produce and what we might seem to require. But the actual gap is even larger than that.

Existing Oil Fields in Decline

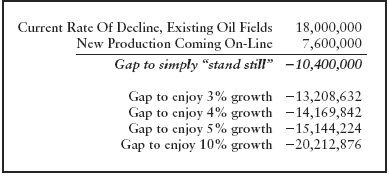

Of course, the above data underestimates the challenge. Based on the IEA estimates of the rate of decline in existing oil fields, we can expect some 18 mbd to vanish over the next five years. This means that if we’re producing 84 mbd in 2009 and don’t bring any new fields on line, we can expect global daily production from existing fields to decline to 66 mbd in 2014.

Fortunately, there are new projects coming on line all the time, but there’s a wrinkle in that story as well. Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA), a U.S.-based company, studied all of the individual projects that oil companies planned to bring on line by 2014 and tallied up some 7.6 million barrels per day of new production, which is nothing to sneeze at. However, when we put this all into one spot, we find that quite a large gap exists between what the world will theoretically require (or demand) and what will be available.

Figure 16.9

presents a summary of all of this information. Given the native decline in existing field output and the new projects still slated to come on line, we need to fill a gap of slightly more than 10 mbd by 2014 just to stand still.

Forget about new global growth; the world may need to find another 10 mbd of production between the years 2009 and 2014 in order to avoid slipping backward. But as we’ve seen, our exponential money/debt system isn’t content with sitting still; it needs to expand. By the time we seek to grow by even 3 percent, the gap is already at 13 mbd. Once you understand the lead times, geological limitations, and engineering hurdles involved in trying to close a 13 mbd output gap, this becomes an improbable task.

In 2009 and 2010, various governmental and industry groups began to observe the same potential supply shortfalls and sounded varying levels of concern over the matter, including: (1) the Industry Taskforce on Peak Oil (UK), (2) Lloyds of London, (3) the UK Parliament, (4) the U.S. Department of Defense, (5) the German military, and even (6) the King of Saudi Arabia, who suggested that perhaps they should leave some oil in the ground for future generations.

In no case did any of these reports connect the dots between energy and the economy as we’ve done in these pages, but it’s only a matter of time before they do.

Peak Exports

However, the most urgent issue before us doesn’t lie with identifying the precise moment of Peak Oil. That is of academic interest, but it’s also something of a distraction, because the economically important event around oil will occur when a persistent gap emerges between supply and demand.

Dallas geologist Jeffrey Brown developed a very simple and clever way to think about the supply and demand problem, which he calls the Export Land Model.

9

Suppose we have a hypothetical country that produces three million barrels of crude oil per day, consumes one million barrels a day, and exports the balance of two million barrels a day. All things being equal, it can export those two million barrels year after year. But now let’s suppose that its oil field output is declining due to depletion issues at a modest 5 percent a year. After 10 years, instead of 2 million barrels a day, this country can now only export 0.89 million barrels a day, or less than half the prior amount. The missing balance has depleted away, and it cannot export what it doesn’t have. Now comes the kicker: Let’s further suppose, quite realistically, that this country increases their internal demand for oil at a rate of 2.5 percent a year. What happens to exports in this case, where internal demand is rising and production is falling? Under this scenario, exports will plunge to zero in less than seven years.