The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment (24 page)

Read The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment Online

Authors: Chris Martenson

Tags: #General, #Economic Conditions, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Development, #Forecasting, #Sustainable Development, #Economic Development, #Economic Forecasting - United States, #United States, #Sustainable Development - United States, #Economic Forecasting, #United States - Economic Conditions - 2009

Find First, Pump Second

It’s impossible to pump oil out of the ground that you haven’t yet found, so another unavoidable fact about oil is that in order to extract it, you have to find it first. Even after a major oil field is discovered, a fairly significant gap exists between the time of its initial discovery and its date of maximum production. There are two main reasons for this: The first is that it takes time to sink the wells and develop the necessary infrastructure to get that oil away from the fields and to market (pipelines, storage facilities, and separating units all have to be sited and built). The second is that a careful approach to production is often required to avoid accidentally damaging the field and possibly stranding some oil in place by pumping too quickly.

To understand this second point, imagine that you have been given an inflatable mattress glued to the floor and filled with creamy peanut butter, and you have the task of getting as much of the peanut butter out of the fill nozzle as possible. You’d probably begin by massaging the mattress from the edges. If at any time any peanut butter gets left behind, say in a small pocket behind the front formed by your hands, it will be lost, stranded forever by geological circumstance and/or economics. This would be no small challenge, and you’d probably be quite cautious as you worked around the edges, carefully avoiding leaving any behind. Likewise, it’s no small challenge for oil producers to maximize the production from oil fields, which are often enormously complicated in their underground topography (imagine that you had to work around random baffles and blind cavities in the inflatable mattress), and they must work carefully and diligently to get as much out of the ground as they can. Given these realities, it can take anywhere from a few years to several decades for any given field to finally achieve maximum production.

In the United States, oil discoveries peaked in 1930 and production peaked in 1970, which yields a gap between a peak in discovery and a peak in production of almost exactly 40 years. Perhaps that 40-year gap was unique to the United State’s particular geology and the oil demand of the times, but the United States is a very large country, and we might reasonably consider this experience to be a plausible proxy for the entire world.

This is where the story gets interesting.

Figure 16.4

shows that worldwide oil discoveries increased in every decade up to the 1960s, but have decreased in every decade since then, with future projections (2010 through 2030) looking even grimmer.

Figure 16.4

Global Oil Discoveries Peaked in 1964

Because discoveries necessarily precede production, a time lag exists between discovery and maximum production.

Source:

Association for the Discovery of Peak Oil and Gas (ASPO).

If you’ve got to find it before you can pump it, and it takes time to develop fields to achieve maximum production, and the global peak in discoveries was in 1964, then we know there’s a peak in production coming at some point. The United States’ experience of a 40-year gap between its discovery and production peaks suggest that perhaps 40 years is as good a starting point as any to begin looking for a world production peak. (1964 plus 40 equals 2004.)

A Global Peak

Now let’s turn our attention to global oil production. In the prior section we made the case that a peak in discovery would lead to a peak in production. That’s simple logic. In July of 2008, oil hit an all-time high of $147 per barrel, and there are a couple of tantalizing clues to be found in the run-up to that event.

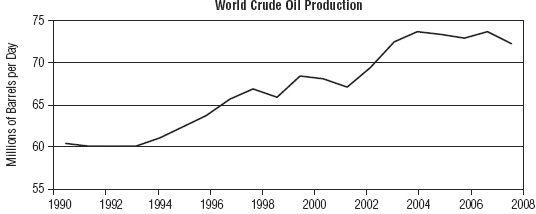

Figure 16.5

shows

only

global conventional crude oil production over the period from 1990 to 2009—it leaves out biofuels and other liquids that collectively amount to roughly 10 million barrels a day.

Figure 16.5

Yearly World Crude Oil Production

Crude oil production was essentially flat between 2004 and 2008, with 2005 being the technical peak.

Source:

Energy Information Administration.

What we see in

Figure 16.5

is that oil has been bumping along a plateau that began in 2004, exactly 40 years after the world peak in oil discoveries. Sound familiar? One fascinating clue here is that even as conventional crude production was flat between the years 2004 and 2008, prices spiked from $50 a barrel to $147 a barrel. If there ever was a strong incentive to get oil out of the ground and off to market, a near tripling of the price of oil would be it. Yet oil production did not rise in response to these market signals. Why not? Could it be that oil production was already at its limits? A second fascinating clue, besides the eye-popping coincidence of the 40-year lag between discoveries and an apparent production peak, is the shape of the bumpy plateau, which mirrors the production peaks seen for such large producing areas as the United States and the United Kingdom. The bumpy plateau is made up of old fields going into decline, new enhanced oil-recovery techniques being applied and new fields coming on line. Add them all together and you get a bumpy plateau.

If we’re already at peak, as this data suggests, then we’ve placed ourselves in quite a predicament. The best possible set of responses to Peak Oil will have been started two decades in advance of the actual peak, a much weaker set of responses one decade in advance, and the worst and weakest set only after Peak Oil has already arrived. Let us fervently hope that the data is misleading us, but at the same time, let us deliberately respond as if the peak has indeed already passed.

Oil and GDP

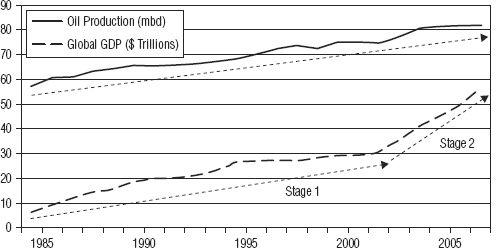

Let’s take another look at the relationship between global GDP growth and oil consumption. Since oil that’s produced is rapidly consumed (approximately 50 days worth of global consumption is above ground at any one time), we can use oil production as our measure of oil demand. Fortunately, we have access to very good data for oil production, which we can compare against global GDP growth, as in

Figure 16.6

.

Figure 16.6

Global GDP Growth and Oil Production

Sources:

Global GDP: Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook

5

& Global Oil Production: Energy Information Administration.

6

Between 1985 and 2003, growth in both oil consumption and GDP enjoyed a stable relationship, marked as “Stage 1.” However, something extraordinary happened to the global economy between 2003 and 2007, where GDP growth accelerated sharply. I’ve marked this as “Stage 2.” This period is characterized by a startling divergence between the rates of growth in oil consumption and GDP.

One explanation for this departure rests with the explosive growth in debt (a.k.a. “credit”), which created a false appearance of growth in world GDP. I call it false because credit-fueled expansions aren’t sustainable, and they inevitably must be retraced, as our island nation example illustrated in Chapter 10 (

Debt

). Building off this debt, much of the GDP growth recorded during the 2003 to 2007 period included an enormous amount of purely paper-based growth that wasn’t a function of what we might consider to be real production. For example, Lehman Brothers grew strongly during that period, but its paper shell-games collapsed, revealing its additions to “growth” to be largely illusory. Ditto for AIG and quite a number of other financial firms; their “growth” was a mirage.

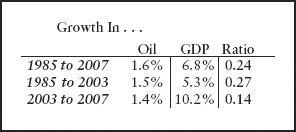

Figure 16.7

compares the yearly growth in oil demand to growth in GDP, displaying both the yearly growth rates for each for various time periods and then the ratio of GDP growth to oil-demand growth:

Using the 1985 to 2003 period as our reference case (because it factors out the late stage of the credit bubble), we can see that every 5.3 percent expansion in global GDP was associated with a 1.5 percent expansion in oil consumption. This works out to a ratio of 0.27, meaning that for every 1 percent expansion in GDP, we should assume a 0.27 percent expansion in oil production (or consumption, if you prefer to look at it that way).

We might also note that the period from 2003 to 2007 was marked by an astonishing rate of global growth at slightly more than 10 percent. This is an astounding rate that would lead to a full doubling of total global GDP in less than seven years if it were to continue. Recalling what we learned about doubling in Chapter 5 (

Dangerous Exponentials

), this implies that the global GDP would produce and consume more goods and services in that same seven-year stretch as in

all of history combined

. Given what we have already learned about Peak Oil, and knowing the strong link between oil use and economic growth, you might want to ask yourself how likely this seems.

Because a 10-plus percent rate of growth is clearly unsustainable, we might instead suspect that our monetary and fiscal authorities would settle for a more modest rate of growth, let’s say 5 percent, in order to keep the Great Credit Bubble expanding and to match the rate of growth between 1985 and 2003. Unfortunately for their plans, it seems that the oil required to support that growth won’t be there.