The Colosseum (12 page)

Authors: Keith Hopkins,Mary Beard

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Travel

What, finally, of the toll in casualties? In individual contests, as we have stressed, slaughter was far less common than our popular image suggests. But what of the aggregate of deaths in the arena? At a death rate of one in six, we have

already estimated 4000 gladiatorial fatalities per year outside Rome. We need to add to that the condemned criminals executed at the shows and the deaths, accidental or not, among animal attendants and hunters; say 2000. The figures for the casualties in Rome itself are harder to estimate, partly because of the enormous fluctuations between years which saw vast displays hosted by the emperor and those when only the regular shows of senators were laid on. It may be reasonable to guess that the capital on average saw something like one third of the deaths in the rest of the empire; say 2000 again. A grand total of 8000 deaths in the arena a year is then our best tentative guesstimate. Not much of a burden, one might initially think, for an empire with a total population of 50 to 60 million people. But, in fact, 8000 deaths per year, mostly of trained muscular young adult males, would be equal to about 1.5 per cent of all 20-year-old men. Seen in these terms, the death of gladiators constituted a massive drain on human resources. Gladiatorial shows were a deadly death tax.

LIONS AND CHRISTIANS

Whatever the death rate of gladiators in the Colosseum, it must have been much worse for the beasts which took part in the shows. There were many more animals than humans involved in the arena displays – both killed and killing. For the big spectaculars at least, the practical arrangements for their capture, transportation and handling must have demanded time, ingenuity and personnel far beyond the acquisition and training of the gladiators. Not for Romans the tame pleasures of a modern zoo, safe entertainment for

young children and indulgent grandparents (though who knows if some perhaps did visit the animals kept before the show in the Animal House near the Colosseum). Their chief pleasure was in slaughter, either

of

the animals or

by

them. Sophisticated this may sometimes have been, in elegantly constructed settings, rocks and trees appearing in the arena as if from nowhere, or tableaux of execution cleverly mimicking (as Martial evokes) the stories of mythology. But it is hard to see how the end result could have been anything other than a morass of dead flesh. As we saw, Dio’s total of animal deaths at the shows opening the Colosseum was 9000, and 11,000 at Trajan’s shows in 108–9. Even if we suspect exaggeration on the part of either emperor or historian, and even if (as must be the case) these lavish spectacles were the exception rather than the norm, there can be no doubt that we are dealing with, for us, an uncomfortable amount of animal blood.

16. A medallion celebrating the ‘munificence’ of the third-century emperor Gordian III. On the left of the Colosseum is the Colossus and the ‘Meta Sudans’ (Domitian’s monumental fountain); on the right a portico appears to abut the building; inside, animals fight.

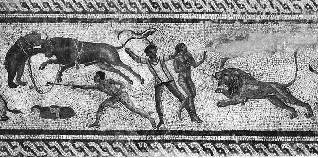

It seems that animal hunts and displays often took place in the morning of a spectacle, conducted by a special class of

trained hunters and animal handlers. Though not gladiators in the strict sense of the word (and without the charisma of gladiators in Roman culture), these

venatores

and

bestiarii

(‘hunters’ and ‘beast men’) were almost certainly drawn from the same underclass, slaves and the desperate poor. One of the training camps in Rome was called the Morning Camp; and it was here, we guess, that these men were trained for the job. Part of their act was to lay on animal displays, the cranes battling cranes, for example, which Dio reported among the highlights of the Colosseum’s opening, or what appears to be a fight between a bull and a mounted elephant on a coin of the early third century, showing the Colosseum. Part was more straightforward hunting. To judge from surviving images in paintings and mosaics, marksmen mostly on foot, but some on horseback, picked off the animals with spears, swords and arrows. It is hardly too fanciful to imagine that graffiti on one of the marble steps in the Colosseum itself, showing scantily clad spearmen rounding up some hounds and chasing or taking aim at a group of bears, represent what the doodling artist was watching, hoped to see or fondly remembered as taking place in the arena (illustration 17).

Most ancient writers assume that the outcome of these contests was death for the animals (and presumably in the process for some of the hunters); in fact when listing the total carnage, they tend to note the number of gladiators who

fought

, but the animals which were

slain

(suggesting that survival was an option for the former, but not for the latter). Modern scholars have occasionally flirted with the idea that some of these acts may have been ‘exhibitions’, in the sense that the animals survived. In fact one idea has been that a particular rhinoceros extolled by Martial for its victory over a

bull at the inaugural Colosseum games is exactly the same animal as a rhinoceros mentioned in a later book of Martial’s poetry, written under the emperor Domitian,

and

none other than the rhino commemorated on some coins of Domitian. He was an animal star, in other words, with several bouts to his credit, much on the lines of star gladiators. Maybe. But we cannot help thinking that a degree of modern sentimentality is creeping in here – although the sheer trouble and expense of acquiring such rare specimens might always have made saving their lives for future appearances a prudent economic move.

17. Graffiti from the Colosseum itself depict the contest of spearmen and animals.

The accounts we have of the animal hunts and shows always lay most stress on the fierce and exotic. In the middle

of the first century

BC

, the great general Pompey (Rome’s answer to Alexander the Great until he was defeated in civil war by Julius Caesar) is said to have laid on, amongst other creatures, twenty (or seventeen depending on who you believe) elephants, 600 lions and 410 leopards. The emperor Augustus, in his autobiography, boasts of ‘finishing off’ a combined total of 3500 animals in ‘African beast hunts’ in the course of his reign (according to Dio, this included thirty-six crocodiles on one occasion). One notoriously unreliable late Roman historian let his imagination run away with him, we must hope, when he listed the animals shown by the emperor Probus in the Circus Maximus (‘planted to look like a forest’) in the late third century

AD

: ‘a thousand ostriches, a thousand stags, a thousand boars, then deer, ibexes, wild-sheep and other herbivores’. On a fantastical variant of the usual procedure, the people were said to have been let in to take what animals they wanted. The same emperor, on another occasion, is said (by the same historian) to have put on a rather disappointing show in the Colosseum. It included a hundred lions which were killed as they emerged sluggishly from their dens, and so ‘did not offer much of a spectacle in their killing’.

The logic of these shows is clear enough. Whether fact or fiction, the killing (and the tales told about it) vividly dramatised Rome’s conquest of the (natural) world. It would, for example, have been hard to watch the slaughter of Augustus’ crocodiles without reflecting on the fact that Egypt had just been brought under direct Roman control. But the practicalities of handling all these animals must surely baffle us. This is partly a question of managing these dangerous creatures in the arena itself. Even if not when it first opened, the Colosseum was eventually equipped with an elaborate system of hoists and cages, which could have delivered animals from the basements, through trapdoors into the arena. But it is hard to imagine how the big animals could have been reliably controlled with the strings and whips that are shown on most of the surviving visual images. Maybe that would have been sufficient for the sort of animals that we suspect made up the regular fare at the Colosseum, the ones ancient and modern writers and artists are much less interested in: the goats, small deer, horses and cattle, even rabbits. With the large and dangerous specimens of the celebrity occasions, things could and did go nastily wrong. Pompey’s elephants, for example, caused all kinds of problems in the Circus in 55

BC

. The crowd reputedly much enjoyed the elephant crawling on its knees (its feet wounded too badly for it to stand up) snatching shields from its opponents and throwing them up in the air like a juggler. But it was hardly such fun when the beasts

en masse

tried to break out of the palisading that enclosed them. It caused, as Pliny remarks in a disconcertingly deadpan way, ‘some trouble’ in the crowd.

18. This mosaic from North Africa shows a condemned criminal (naked and held by his hair by a ‘guard’ in a tunic) facing a murderous lion. Not as in the comforting ancient story of Androcles, famously adapted by G. B. Shaw: there the lion remembers an earlier kindness of his human victim, who had once removed a thorn from his foot, and refuses to attack him.

It is even more amazing to contemplate the organisation and expertise that must underlie the acquisition and transport of these wild animals. True, if we think of the more run-of-the-mill shows, then probably the animals could be supplied by local livestock markets – and some emperors apparently kept a herd of elephants just outside Rome, under the charge of a ‘Master of the Elephants’. But – that apart – how were the more impressive and exotic victims obtained? The scale of the problem of animal procurement can be gauged by a single comparison. In 1850 a young hippo was

brought to western Europe, the first for more than a thousand years, and caused a great stir in London, where it ended up in the Regent’s Park Zoo under the name of Obaysch. It took a whole detachment of Egyptian soldiers and a fivemonth journey from the White Nile to transport it as far as Cairo. A specially built steamer equipped with a 2000-litre water tank took it from Alexandria to London, accompanied by native keepers, two cows and ten goats to provide it with milk. Compare that with the five hippos, two elephants, a rhino and a giraffe killed (according to an eye-witness account) by the emperor Commodus himself in a single twoday exhibition in the late second century

AD

.

How did the Romans do it? How did they capture the animals in the first place, without the convenient aid of the modern tranquillising dart? The answer seems to be by a variety of traps and pits and the cunning use of human decoys dressed up in sheepskins! And how did they manage to get these fierce and no doubt frightened creatures delivered from distant parts of the empire to the capital alive and in good fighting condition? Sceptics will answer that they often did not. Symmachus, after all, was disappointed with his emaciated bear cubs and maybe more corpses arrived than living animals. All the same, behind the exaggeration and the failures that are not trumpeted in ancient literature, the stubborn reality remains that on occasion at least large numbers of these beasts did make it to Rome. Private enterprise and personal arrangement played their part. In the late 50s

BC

, as we know from his surviving letters, Cicero, the new governor of the province of Cilicia (in modern Turkey), was being badgered to get hold of some panthers for shows of his disreputable friend Marcus Caelius; Cicero was evasive, claiming that the animals were in short supply. But later it seems that state requisitioning of animals also made use of army detachments. It was perhaps a convenient way of keeping the troops occupied while on peacetime garrison duty. We know from inscriptions, for example, of a ‘bear-hunter’ serving with the legions on the Rhine and of fifty bears captured in six months in Germany.

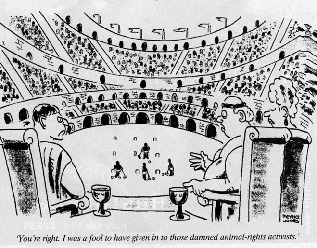

19. A modern variant on the Christians vs Lions ‘joke’.

Animals were not only brought to the Colosseum in order that they themselves should be killed. They were also used to kill criminals and prisoners in the executions that took place in the arena as part of the shows. One notorious form of execution was ‘condemnation to the wild beasts’ (‘

damnatio ad bestias

’), where prisoners, some tied to stakes, were mauled and eaten by the animals. This is the fate to which Christian prisoners were often sentenced and is the origin of all those novels and films which take as their centrepiece the clash between ‘Christians and Lions’, not to mention the series of sick jokes along the lines of ‘Lions 3, Christians 0’.