The Colosseum (16 page)

Authors: Keith Hopkins,Mary Beard

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Travel

Figure 3. Cross-section of the Colosseum (reconstruction).

Of the two entrances on the shorter axis, normally taken to be used by celebrity spectators, only that on the north survives; but the symmetry of the monument would suggest that it was mirrored on the south. There are still traces at the north of a vestibule that would once have protruded out from the line of the main exterior wall. Putting this evidence together with the first-century sculpture of the Colosseum (illustration 21) and with images on coins allows us to reconstruct a monumental entranceway on each side, topped by a four-horse chariot presumably carrying the emperor. If the Colosseum were one of the key contexts in the city of Rome for the display of the emperor, imperial statues would have been a particularly resonant and appropriate image over these two principal entrances.

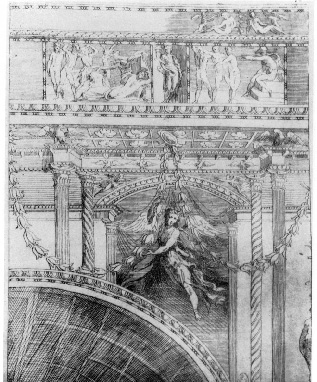

Even more striking is the evidence we have for the stucco decoration at the north entrance. Although only a very few fragments are still visible, when they were much better preserved

these stuccoes were drawn by Renaissance artists (including Giovanni da Udine, a pupil of Raphael, who based some of his designs for the Villa Madama on them). The exact interpretation of these is not made easier by the fact that different artists depict them rather differently – divergences that may themselves suggest that the stuccoes were not as well preserved in the Renaissance as they appear, or at least that a degree of imagination has gone into these apparently antiquarian documents. Nor is the date certain: perhaps part of the original first-century decoration, more likely part of a later makeover. But whatever they represent and of whatever date, they are precious evidence for the lavish decoration of the building that has now almost entirely disappeared. Other fragments of brightly painted plaster survive from the corridors, on the basis of which it has been tentatively suggested that vivid colours were widely used in the building’s early phases, toned down to something rather less flashy later.

The main principles of the original seating plan are, as we have seen, clear enough: the seats were ranked hierarchically from the ringside to the top of the house. We can also trace on the ground plan the routes that must have led to the different areas of the auditorium (

figure 1

): senators, for example, would have entered and made straight for the seats on the podium at the front (Route A, and repeated round the building); those sitting at the highest level would have made straight for the stairs (Route B, repeated), without any opportunity to mingle with the aristocrats, and would then have emerged through a balustraded opening into their designated block (some of the late decorations of these balustrades survive). On the other hand, reconstructed cross-sections of the building (like our

figure 3

), which confidently mark the exact position of the seats and the number of rows, are based on much less firm information than their clear lines would suggest. The simple reason for this is that no seating survives and so all reconstructions are based on a more or less rough guess of what would fit on the skeleton that remains. This problem is especially acute in the elite sections of the building. The podium on which the (movable) senatorial seats rested certainly extended further down than what now appears, to a casual observer, to be the boundary wall of the arena. This is in fact the back wall of a tunnel which carried at least part of the elite seating above it (illustration 20 and

figure 3

) and probably acted as a service tunnel around the arena’s edge – with openings through its now largely destroyed front wall onto the arena itself. But the exact extent of the senatorial area is uncertain, as is its form: it is sometimes reconstructed as a sloping area, sometimes as stepped. All these uncertainties make an accurate estimate of how many people it could accommodate (

p. 111

) very difficult.

22. The elaborate stuccoes which survived at the north entrance of the Colosseum until, at least, the sixteenth century.

The most elite seating of all was in the boxes that we assume took pride of place on the north and south sides of the arena, and are regularly illustrated in imaginative versions of the Colosseum from Gérôme to Ridley Scott and beyond (illustration 8,

p. 57

). Nothing remains of these, but they must have been located at the ringside, approached by the elaborate entranceways at north and south. There is strong evidence to connect the position at the centre of the southern side with the emperor himself, for an underground passageway has been discovered which gave access to the ringside at this key point from somewhere outside the building to the east. About 40 metres of it has been excavated but the starting point has

not been identified (

figure 1

). What is clear, however, is that it was an insertion (possibly under the emperor Domitian soon after the building was opened) into the original structure and that it was elaborately and richly decorated. The walls were originally faced in marble or alabaster, later replaced with frescoed plaster; there was lavish stucco on the vault and in niches; the floor was covered in mosaic. It seems very likely indeed that this passageway gave the emperor private access to his box, in addition to the main entranceway on the ground floor. In fact, its popular name is now ‘the passageway of Commodus’, so called after a story in Dio that Commodus was once attacked by a conspirator ‘in a narrow entrance way’ in the Colosseum – a nice illustration of the emperor’s vulnerability even (or especially) here. If the connection is right, he would have been attacked in his own private corridor, leading to his own ceremonial seat.

If the southern box was for the emperor and his party, what of the northern box? Different scholars and different tourist guides come up with plausible, and not so plausible, ideas. Some imagine that it might have provided overflow accommodation for minor royals and hangers-on. Others suggest that this would have provided suitable accommodation for the Vestal Virgins (whom Gérôme chose to put next to the emperor). It could also have provided for magistrates, particularly those sponsoring the shows. No one knows. And, in any case, it might not always have been used by the same people, or even used at all.

Ancient spectators, sitting in any of these locations, would have enjoyed a view quite different from that offered to the modern visitor. Over the complicated web of foundations that we now see would once have been a wooden

floor (not unlike the small section inserted by the Italian Antiquities Service (illustration 20) to help visitors more easily imagine the original appearance. The ancient flooring would have been covered with sand (‘

harena

’ in Latin, hence the modern word ‘arena’) whether to prevent slippage, or soak up the blood and the urine, or both. But the security of the spectators must have been as big an issue as the general salubriousness (or otherwise) of the fighting space. There would have been something in the order of a 4 metre drop between the senatorial seating and the arena floor, but that might seem rather close for comfort in the face of a couple of angry elephants. Almost certainly there were more safety measures in place. A graffito found during nineteenth-century excavations in the Colosseum has been (rather optimistically, we feel) interpreted as a picture of latticework balustrading around the senatorial podium; but, in any case, there must have been some kind of further barrier in that position, whether in this form or not. Roman ingenuity, however, could do better than that. The two rustics, whose visit to an earlier amphitheatre was the subject of an elegantly whimsical poem in the reign of Nero (

p. 38

), pick out the clever device designed to keep the animals away from the spectators. This seems to have involved sets of ivory inlaid rollers around the edge of the arena, which would prevent any animals (or vengeful gladiator, for that matter) getting a foothold, and an extra fence laid some way into the arena, with a net (a

golden

net in the poem) spread out from it to the podium where the elite were sitting. It is often assumed that some such devices would have been used in the Colosseum too. Much as they appreciated their ringside view, the Roman aristocracy were

no doubt as keen on self-preservation as we are, and suitably cautious.

THE COLOSSEUM BELOW GROUND

Confronting the modern visitor to the Colosseum, at the heart of the building, is a mass of subterranean walls, which have been the subject of intense debate and sometimes bitter controversy since they were first re-discovered in the early nineteenth century (although it was not until more than fifty years later that any of them went on permanent display). All kinds of issues have been argued over: the date of their construction and their different phases, the exact function of the different parts and (as we explained in

Chapter 3

) the implications of all this for the question of whether or not the inaugural celebrations of the building in

AD

80 could possibly have featured a mock sea battle. But before we explore some of the details of these arguments, and in particular the colourful controversies that seethed over a few years in the early nineteenth century, it is worth considering briefly those aspects of this subterranean world of brick masonry that are not (or not much) in dispute. For the minor details have often swamped more basic, but more important, conclusions.

What is now for us the centrepiece of the monument is ‘below stage’. It is an area larger than the arena itself, if only because at each end of the major axis there are storerooms and (at the east) a corridor leading underground directly to one of the main gladiatorial training camps, with its own practice arena, known as the Ludus Magnus (literally the ‘Big camp’). It is a maze of corridors and hoists which once

brought caged animals to the surface via trapdoors in the wooden floor. Stage scenery, which might transform the arena into a world of make-believe, could also be lifted in this way. It is still possible to see the rope burns in the stone edges of some of the lift wells; and archaeologists have uncovered a few of the bronze fittings which held the revolving capstans which were integral to the hoisting machinery. A clever system it certainly is (though exactly how a hippopotamus would have fitted in is hard to imagine); but this must also have been a truly horrible underground world. The maze of corridors would have been dimly lit by skylights at the edge of the arena, and elsewhere by smoking oil lamps. It does not take much imagination to see that this must have been a hive of sweating labour: slaves, skilled stage-hands, animal trainers, hunters, wild animals in their cages, chained criminals and presumably some of the gladiators, all packed together in tiny cells and passages. Above they would have heard the awful thudding of the hunts and contests. Today the noise of just tourists above, ambling across the reconstructed section of floor, is bad enough (although, as these areas are not usually open to the public, most visitors do not have the pleasure of sharing this terror). An elephant or two is hard to contemplate. This was a hell-hole.

Most of the hoisting shafts visible today date from around 300, with some later repairs. The current orthodoxy is that the original plan did not include any such system occupying the area under the arena, and that during the reign of Titus animals would have been let into the arena using hoists fixed on the perimeter wall – or even from the service tunnel under the senatorial podium. The first versions of these major substructures are generally thought now to date from the reign

of Titus’ successor, Domitian. But this is what the controversy has been about.

The subterranean structures first began to be systematically uncovered by Napoleon’s archaeologists, working with the Pope’s archaeological team, during the French occupation of Rome between 1811 and 1814; though they had not reached the bottom of the area beneath the arena before the work was stopped by flooding. Nonetheless, even these partial discoveries prompted a furious row and angry exchanges of pamphlets between leading scholars (sometimes hiding behind unlikely pen names) that were satirised in cartoons of the time. There were three main parties. The first was the papal archaeologist, Carlo Fea, who is now probably best known for producing an Italian edition of J. J. Wincklemann’s

History of Art

, still widely used. Fea argued that the substructures that had been revealed were not ancient at all, but medieval, and that the original surface of the arena had not therefore been on top of these substructures, but underneath them several metres below the level of the seating; this was the only way, he argued, that it was possible to conceive of a naval battle in the Colosseum, as Dio’s testimony demanded, which would not have been feasible with all those masonry insertions. Against him, an architect, Pietro Bianchi, and the Professor of Archaeology at the University of Rome, Lorenzo Re, contended that the substructures were contemporary with the original building (they were, after all, aligned with it) and that the arena floor had been laid on top of them. In support of this they pointed out that, if the fights had taken place at the low level Fea suggested, then great swathes of the arena would have been out of the line of sight of many in the audience, who would not have been able to see into what was to all intents and purposes a pit. They also relied on the evidence of the late Roman inscription commemorating the repair of the arena after an earthquake (

p. 123

) – for only if it had been elevated on brick and masonry supports could it have been destroyed by an earthquake. As for Dio’s claim about a naval battle, he must have been wrong; Bianchi and Re preferred to follow the evidence of Suetonius who, as we saw (

p. 43

), located the naval battle elsewhere. The final player was a Spanish priest and antiquarian, Juan Masdeu, who tried to steer a middle path, casting himself as a ‘pacifier’ of the warring factions. He judged that Fea was correct on the original form of the Colosseum, but that the substructures had been inserted in the later third century and the arena floor raised to go on top of them only then. So Dio could have been right about a naval battle there in

AD

80.