The Colosseum (10 page)

Authors: Keith Hopkins,Mary Beard

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Travel

Beyond the physical dangers they faced, gladiators were marginalised in a civic and political sense. Many were of slave

status anyway, which meant that they had only the most limited legal and personal rights. But even those who were by origin freeborn Roman citizens suffered a whole series of penalties and stigmas when they became gladiators, which in many respects amounted to losing their status as full citizens. It involved much the same ‘official disgrace’ (‘

infamia

’ in Latin) as prostitutes and actors suffered by virtue of their profession. We know of Roman legislation from the first century

BC

that prevented anyone who had ever been a gladiator from holding political office in local government; they were also not allowed to serve on juries or become soldiers. Even more fundamentally they seem to have lost that crucial privilege of Roman citizenship: freedom from bodily assault or corporal punishment. Roman civic status was written on the body. Part of the definition of a slave was that, unlike a free citizen, his body in a sense no longer belonged to him; it was for the use and pleasure of whoever owned it (and him). A gladiator fell into that category, as the notorious oath said to have been sworn by recruits when they entered the gladiatorial camps proclaimed. Its terms no doubt varied from place to place, but Seneca quotes a version that has a gladiator agreeing on oath ‘to be burnt, to be chained up, to be killed’. Such a promise of bodily submission was completely incompatible with what made a free Roman citizen free.

It is hardly surprising then that gladiators are often treated as the lowest of the low in Roman literature, and symbols of moral degradation. Not for ancient Rome the modern political heroisation of Spartacus, the first-century

BC

gladiator who led a, temporarily successful, rebellion of slaves against their Roman oppressors and has starred in countless modern novels, movies, ballets, operas and musicals

– including in 2004 a French blockbuster show

Spartacus le Gladiateur

, who ‘dreamed of being free’. By contrast, Roman politicians looking for a slur to cast on their rivals would often reach for the term ‘gladiator’. And Seneca again, when writing a rather pompous philosophical essay in the form of a letter of condolence to a man who had just lost his young son, attempts to cheer him up by reminding him of the boy’s uncertain and possibly ghastly future: he might have squandered his wealth and ended up as a gladiator. It is hardly surprising too that we know of repeated attempts by the Roman authorities legally to prohibit senators from fighting as gladiators in the arena.

But this prohibition should give pause for thought. For if the gladiators were so completely despised and abominated, why on earth would legislation have been necessary to prevent senators from joining them? One answer is that these regulations were more symbolic than practical. The function of law is often to proclaim the importance of boundaries, rather than literally to prevent people crossing them. The reason most of us do not commit incest is not, after all, that there is a law against it. Here we might be seeing another instance of Roman insistence that there was a firm line to be drawn between fighters in the arena and civilised (especially elite) Roman society.

There is, however, plenty of evidence to suggest that gladiators were as much admired and celebrated as they were abominated. Far from just flirting with the idea of gladiatorial combat, some members of the Roman elite did enter the arena; even some emperors (admittedly ‘bad’ ones) left the imperial box in the Colosseum and joined in the fight – as we shall see later in this chapter. The admiration of the gladiators took a variety of forms. While philosophers such as Seneca might with one breath deplore the degradation of the gladiators or their corrupting effect on the crowd, with the next they were seeing in the arena an example of true courage, of a ‘philosophical’ approach to death, even a model for how the truly wise man should act. More generally Roman households seem to have been littered with images of gladiators, combat and equipment. The lamps with gladiatorial decoration buried alongside the woman from Roman London are only one example among thousands upon thousands of such objects, from the elegant to the kitsch: not just the expensive mosaic floors or paintings with scenes of the arena (though there are plenty enough of them decorating up-market houses all over the empire), but ivory knifehandles carved as gladiators, lamps moulded in the shape of gladiatorial helmets, even, from Pompeii, a baby’s bottle with the image of a gladiator in full fight. And this is not to mention the signet rings, the glass beakers, the tombs, marble coffins, water flasks, candlesticks – all displaying characters from the arena. How any of this relates to the odd custom of Roman brides parting their hair with a spear that had been dipped into the blood of a dead gladiator is frankly a mystery. It may anyway have been more a piece of antiquarian folklore than a regular practice, as puzzling and quaint to the Romans as it is to us. One of the Roman scholars who did puzzle over it came up with various possible explanations. Perhaps the union of the spear with the gladiator’s body symbolised the bodily union of husband and wife. Perhaps it was supposed to help her chances of bearing brave children. Who knows?

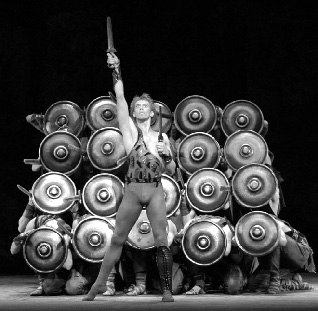

15. Spartacus, the most glamorous gladiator ever and freedom fighter

avant la lettre

, here stars in Khachaturian’s Soviet ballet

Spartacus

(in a production at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in 2004). The end of the story is that Spartacus was resoundingly defeated by the Roman legions.

The strongest image of the gladiator in Roman culture,

however, was as a virile sex-symbol. Graffiti from Pompeii, probably written by the gladiators themselves (and so a boast as much as a comment), call a Thracian by the name of Celadus (or ‘Crowd’s Roar’) ‘the heart-throb of the girls’ and his partner Cresces (perhaps ‘Bigman’, a

retiarius

) ‘lord of the dolls’. It was in fact a standing joke at Rome that women were liable to fall for the heroes of the arena. The satirist Juvenal, writing around

AD

100, famously turned his wit on a senator’s wife, Eppia, who had apparently run off with a sexy thug from the Colosseum:

What was the youthful charm that so fired Eppia? What

was it hooked her? What did she see in him that was worth

being mocked as a fighter’s moll? For her poppet,

her Sergius

was no chicken, forty at least, with one dud arm that

held promise

of early retirement. Deformities marred his features –

a helmet-scar, a great wen on his nose, an unpleasant

discharge from one constantly weeping eye. What of it?

He was a gladiator.

That makes anyone an Adonis;

that was what she chose over children, country, sister,

and husband: steel’s what they crave.

The joke here is, of course, on the woman, satirised for an insatiable sex-drive that leads her to abandon everything for this brute. This is Roman misogyny speaking loud and clear. But the last line of this extract hints at a telling pun. ‘Steel’s what they crave’. The Latin is ‘

ferrum

’ – literally ‘iron’, or ‘sword’. Another common Latin term for sword (and one embedded in the word ‘gladiator’ itself) was ‘

gladius

’ – which

was also Latin street-talk for ‘penis’. The point about the gladiator is that he was, for better or worse, as one modern historian has aptly put it, ‘all sword’.

Juvenal is satiric fantasy. But similar stories, true or not, were told of historical figures too. The empress Faustina, for example, wife of the philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius and mother of the notorious Commodus, was rumoured to have conceived Commodus during an affair with a gladiator. One particularly lurid ancient account claims that when she confessed this passion to her husband, he consulted soothsayers who recommended that he have the gladiator killed; after this he was to make his wife bathe in the dead man’s blood and then have sex with her. The story goes that he followed these recommendations, and then brought Commodus up as his own son. Historians have, understandably, been dubious about this tale, and guess that it was invented to provide a convenient explanation for Commodus’ obsessive enthusiasm for the arena.

A notorious find from Pompeii is often seen as positive confirmation of the fondness of upper-class Roman women for rough gladiatorial trade. In the excavations of the gladiators’ barracks, the skeleton of a heavily jewelled lady came to light – presumably, it has often been suggested, caught in the act with her paramour, trapped for eternity (as every adulterer’s nightmare must be) in the wrong place at the wrong time. If so, she was taking part in a very squashed session of group sex. For in this tiny room were found not only the rich lady plus partner, but no fewer than eighteen other bodies, children included, plus a variety of bric-à-brac, chests with fine cloth and so forth. Much more likely we have the remains of a group of people fleeing the city with their prize

possessions who had taken refuge in the barracks when the ash and pumice rained too hard, never to re-emerge. But if this turns out to have been no adulterous tryst after all, it is still the case that in the Roman imagination the gladiator was a figure of larger-than-life sexual power.

How then do we account for these conflicting images? How do we explain why a figure of such social and political stigma was also the object of admiration and fantasy? All kinds of ideas have been canvassed. In part we are no doubt dealing with a common fascination of elite culture for its opposite: a combination of

nostalgie de la boue

and Marie Antoinette playing at milkmaids (or, for that matter, female members of the British royal family cavorting around London clubs dressed up as policemen). In other words, gladiators were not sexy and exciting

despite

being beyond the social pale, but

because

they were. Maybe also, in a highly militaristic culture such as Rome, gladiatorial combat played a special role. Whether the Romans were engaged in active military combat or not (and long before the first century

AD

fighting normally took place miles from the centre on the remote frontiers), the lust for battle was replayed in – or displaced into – the arena, and military prowess found its expression in the skill of the gladiators; this could not simply be abominated. Even more important, though, must have been the power of the spectacle itself. To be the centre of attention of a vast crowd is always empowering. Hence, for example, the almost heroic status of the condemned criminal in early modern Britain giving his gallows speech in front of those assembled to watch his hanging; and hence, in part at least, the celebrity of modern football stars. To be watched by tens of thousands of people in the Colosseum, to have all eyes on

you, transcended the invisibility of social disadvantage. Emperors realised this as well as anyone: when they left the imperial box to take their place in the arena, it was partly a gambit to recapture the gaze of the crowd. The emperor always risked being upstaged by the abominated creatures whom everyone was watching.

Yet there was more to the allure of the gladiator than the familiarising image of the modern footballer might suggest. The gladiator was a crucial cultural symbol at Rome because he prompted thought, debate and negotiation about Roman values themselves. Of course, there is something tautological about that claim: all crucial cultural symbols prompt negotiation about their society’s values; that’s what makes them ‘crucial cultural symbols’ in the first place. Nonetheless, gladiators and gladiatorial combat do focus attention on many of the ‘jagged edges’ of Roman culture: on the question of what bravery and manliness consist in; on power and sexuality; on proper control of the body; on violence and death and how to face it. Their position in Roman society, and in the Roman imagination, was bound to be contested and ambivalent.

Or so it must have been from the point of view of the audience, and of those Romans who quaffed their wine from gladiator glasses, or sealed their letters with a gladiator signet-ring. What we are missing (apart from some blokeish boasting on the part of Celadus and Cresces and the occasional ghoulish bon mot on a tombstone) is the point of view of the gladiators themselves. There is no account from any arena fighter of what it felt like on the other side of the barrier that separated the spectators from the slaughter. The hints we get, however, suggest terror was as powerful a feature as heroism. This is presumably the message of

Symmachus’ twenty-nine Saxons who pre-empted the agony and humiliation of the performance by strangling each other. Even this is rather upstaged by a tale told by Seneca of another arena performer, an animal hunter, not technically a gladiator. The man, a German by birth, went off to the lavatory just before the show (‘the only thing he was allowed to do without surveillance’); there he grabbed the stick with a sponge on the end (which was the Roman equivalent of lavatory paper) and rammed it down his own throat, suffocating to death. Seneca treats this as an instance of consummate courage (‘What a brave man! How worthy of being allowed to choose his own death!’). We might detect desperation and terror, as well as bravery.