The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (84 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

22. B

ATTLE

O

F

C

HIPYONGNI,

F

EBRUARY

13–14, 1951

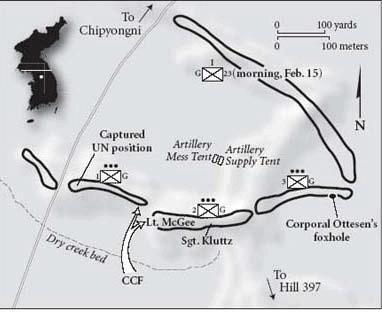

The Chinese had, however, discovered a blind or dead spot right in the center of his position. It was a dry creek bed, about four feet deep, almost like a giant ditch, that seemed to come directly from Hill 397 and empty out right on top of the George Company position. It was quite literally a natural channel into the George Company sector and allowed the Chinese very good cover right up to the foot of McGee’s small hill. The Chinese could hardly have done better, if months earlier, knowing that there might be a battle here, they had carved the channel out themselves. McGee knew it was a dangerous avenue into his position, but there was not much he could do about it. With dawn just arriving on the morning of the fourteenth, he noticed some Chinese soldiers near the mouth of the creek bed, and told Bill Kluttz, his platoon sergeant, to fire his rocket launcher at the spot. Kluttz hit a tree, which gave him an air burst illuminating about forty Chinese soldiers, who rose up out of the cover of the trees and started running back across the flat land right in front of the American position; the Americans opened up with their machine guns and caught most of them in the open field. Now they knew for sure that the Chinese were going to keep on using the creek bed for protection.

COLONEL PAUL FREEMAN

thought the first night of the battle had gone reasonably well. All positions had held and his casualties were surprisingly low. He knew he did not entirely control the course of the battle—the Chinese would do that, depending on how many men they were willing to feed into the fight. He worried, though, about his supply of ammunition. There were so many attackers that, no matter how much his men had, it probably was not going to be enough. The Air Force was trying to air-drop more, but most of it was falling outside the perimeter. Still, morale was high, which was a critically important factor in any siege. It was almost as if his men were eager to be here, and anxious to be given a chance to make up for Kunuri.

Freeman kept busy during the night moving around the perimeter, checking in with his different subordinate commanders. If there was a place of vulnerability, it was to the south and southwest, where George Company and the French battalion were potential targets. But he had already spoken to Jim Edwards, the commander of the Second Battalion, which included George Company, about moving reserve units up to reinforce those positions. Then, at daybreak of the fourteenth, a Chinese 120mm mortar round landed right next to Freeman’s tent. The regiment’s intelligence officer, Major Harold Shoemaker, was grievously wounded and died a few hours later; several other officers, including Freeman, were wounded less severely. He took a small slice of shrapnel in his left calf, which did not seem serious: Freeman had been lying down on his cot when it happened, and had just reversed his position so that his feet were where his head had been. He and Lieutenant Colonel Frank Meszar, his good friend and the regimental executive officer, later joked about what might have happened if he had not reversed his position on the cot. It was, they decided, the kind of luck you needed in battle. While the wound itself did not seem that bad, there might have been a break in the lower leg that would have to be dealt with later. Captain Robert Hall, the regimental surgeon, quickly dressed the wound, gave Freeman two aspirin, and told him to get in touch if he had any problems.

23. M

CGEE

H

ILL,

F

EBRUARY

13–15, 1951

Freeman continued to visit forward positions, often virtually alone, with a limp. But the wound was what Ned Almond had been waiting for, and using it as his excuse, he moved immediately to relieve Freeman of his command in the middle of a battle. He had wanted to put one of his own boys in charge of the Twenty-third for some time. A few days earlier, he had made his first try. Irritated because he thought Freeman was not forcing his men to use dry socks to prevent trench foot and frostbite, he sent Lieutenant Colonel John Chiles,

his operations officer, to Ruffner to tell him to relieve Freeman. That was the last thing Ruffner wanted to do with a serious battle looming. He looked at Chiles and replied, “Do you know what? My radio just went out of whack. I have no way in the world of reaching Paul Freeman.” That provided only a brief stay of execution.

The senior officers in the Twenty-third were furious that Almond would use a marginal wound as an excuse to change commanders in the middle of a battle that was going well, and was about to increase in intensity. To substitute for a much admired officer someone no one knew and who would always be considered part of a coup was appalling, they thought. Dr. Hall had received a call from Colonel Gerry Epley, division chief of staff, almost as soon as word of the wound had reached higher headquarters.

“How serious is the wound?” Epley asked.

“It’s not that serious,” Hall answered. “Maybe under normal conditions you might evacuate him for treatment. But these aren’t normal conditions.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“Well, this is a tough place and this is a very tough battle and he’s the one man holding the regiment together. We’re surrounded, we’re going to be short of ammo. The men can see that some of the ammo drops are falling short, but they absolutely believe in Freeman, and they believe that he’ll get them out of here. The Twenty-third Regiment believes in itself because he’s led them before. Without him I think it’s a different regiment. Evacuating him would be unnecessary, unwanted, and undesirable.”

Hall instantly knew he had been too candid. Epley’s voice changed. He was furious, Hall realized: how dare a surgeon tell him what to do on a military matter. “Don’t you dare to presume to tell me about tactical matters! We don’t need any of that from you. I asked you for a medical judgment. I just want to know how deep the wound is. That’s all the answer I need from you.”

But Hall thought he would give it one more shot. He was not, after all, a kid, and he had no time for the politics of Division or Corps headquarters now. He had been a combat surgeon in World War II, had fought in the Battle of the Bulge, and had gone into civilian practice for a time. When Korea began, he had asked to go back on active duty and volunteered specifically for the Second Division after it had been hit at Kunuri, because he had lost some close friends up there. In all of this he had been motivated by old-fashioned loyalties. Now, he felt, those same loyalties gave him the right to speak candidly. Besides, who knew more about the mood of the regiment than a doctor, whom soldiers often told things they would never tell other officers. This regiment, he insisted to Epley, more than most, believes in its commander, and takes much of its strength and identity from his presence and leadership. It would

be extremely dangerous for regimental morale if he were pulled out. Epley signed off angrily, and Hall knew they were going to pull Freeman anyway.

Freeman was enraged. This was his battle and his regiment, and he did not want to leave. There was nothing worse in terms of unofficial Army codes than to be relieved of command in the middle of a battle. “I brought them in,” he told headquarters during one call, “and I’ll bring them out.” He tried talking Ruffner out of it, but in a fight between Almond and Freeman, Ruffner was powerless. Freeman finally turned the matter over to George Stewart, the one man at Division whom he trusted. Freeman told Stewart he was not going to give up his command or be evacuated. Being relieved like this was the worst disgrace that could befall a commander, a career ender. Stewart, who knew Freeman was at least partially right, listened sympathetically. No one, he said, was going to question his performance. It was not going to damage his career, but if he did not leave as ordered there could be far more serious consequences. Finally, Freeman realized he had no choice. In the military, after all, you could not challenge orders.

But later that day, when Chiles flew in, Freeman managed not to be at the little airstrip to go out on the same plane. It would be used to take out wounded men, but not the outgoing regimental commander. Chinese mortar fire was falling on the strip as the plane landed, and the pilot needed to get out quickly. For the moment, the Twenty-third had two regimental commanders. “I told Chiles to find a shelter and stay out of my way until my departure,” Freeman said years later. Chiles was shrewd enough to stay in the background and let Freeman run the show through the night of the fourteenth and well into the late morning of the fifteenth. Even when Chiles officially took command at midday on the fifteenth, he let the regimental exec, Frank Meszar, who knew the relative value of all the subordinate commanders, continue in Freeman’s role.

M

ATT RIDGWAY HAD

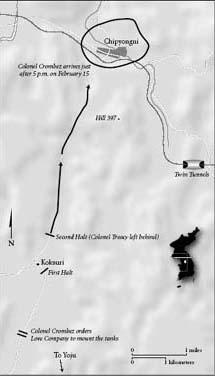

given Paul Freeman his word that if the Chinese attacked in full force, he would send help, and he intended to make good on his word. He was prepared to send the British Commonwealth Brigade, and the Fifth Cavalry Regiment under the command of Colonel Marcel Crombez. The Fifth Cav was a part of the First Cavalry Division. But help was not going to arrive any too quickly. The Commonwealth Brigade had a better, more direct route to Chipyongni, but it had run into an enormous Chinese blocking force and quickly found itself embattled and stalled, hardly in a position to rescue another trapped force. So Crombez was ordered by Major General Bryant Moore, the neighboring Ninth Corps commander, to get to Chipyongni in a hurry. In a case like this unit titles are often confusing: the First Cav itself was not a cavalry division, it was what the Army calls straight leg, that is, regular infantrymen; but the Fifth Cavalry Regiment, a part of the First Cav, was armored, and had been held in reserve at that time by Ninth Corps, at a base near Yoju. When he first started out on the rescue at Chipyongni, Colonel Crombez’s force had twenty-three tanks, three infantry battalions, two battalions of field artillery, and a company of combat engineers. It was a not inconsiderable force. Crombez would have plenty of firepower. In addition, if things went badly, there was always the possibility of dispatching air cover to protect him.

Crombez first heard about the mission on the morning of February 14, when General Moore called to say that it looked like he might be used in the relief of Freeman’s force. At 4

P.M.

, Moore called back, telling him he would have to move out that night to relieve Freeman’s regiment—“and I know you’ll do it.” An hour later, Charles Palmer, newly promoted to two stars and made the commander of the First Cav, arrived at Crombez’s CP and confirmed the order. Crombez was something of a controversial figure—a man who dressed with dash, wearing a cavalryman’s yellow scarf (as if he were fighting the Indians back in the Wild West), having an oversized eagle painted on his helmet, and pinning a grenade on his harness much as Ridgway did. He also carried

with him a blue poker chip that he would flip up and down while talking with his men, telling them they had to know when to play their blue chip—the implication being that a great combat commander had a sixth sense about battle and always knew when to strike. Some in his unit thought, however, that he did not fight with equal dash. He had, until then, seemed the possessor of a self-invented mystique, one not actually forged on the battlefield. Some of the men under him thought he sought glory too intensely, wanted a star too badly, and did not seem adequately committed to them. “Brave, yes. Professional, no,” Clay Blair quoted a fellow West Pointer saying.

By the time he had his force ready to move, much later on the fourteenth, it was already dark, not the ideal time to push forward on roads where the Chinese might already be dug in. That first night Crombez made it to Yoju, about ten miles south of Chipyongni. There his units waited while the engineers built a bypass around a blown-out bridge over the Han River. Having finally managed to clear the Han on the evening of the fourteenth, his tanks were slowed by another blown bridge over a creek near Koksuri, about five miles from Chipyongni, and never really got moving until the morning of the fifteenth. Paul Freeman, monitoring Crombez’s progress by radio, knew that no relief party was going to make it through on the fourteenth. Meanwhile the heaviest fighting yet at Chipyongni was taking place on the night of the fourteenth and into the morning of the fifteenth. Freeman, aware that the relief mission was moving more slowly than expected, then requested all the air strikes he could get, but almost nothing came—because the Air Force was so committed to the fighting at Wonju. What he did get was a light spotter plane—the Firefly, the men called it—that dropped flares; a wonderful addition to the battlefield, Freeman later said, because it turned “night into day.” His men, he knew, were going to have to hold out a second night before help arrived.

IN THE ANNALS

of the Korean War few incidents are as controversial as that of Marcel Crombez’s final dash to the rescue at Chipyongni. Yes, he got there, and he got there in time, and yes, what he did was what Matt Ridgway had ordered him to do. But there was an unnecessary recklessness to it, which resulted in unnecessary losses among the infantrymen who accompanied him that many involved felt reflected an almost cavalier disregard for their lives. That he had put the mission above the proper care and treatment of his own men angered those infantrymen who survived, and left a bitter aftertaste in the accounts of historians who believed the same results could have been achieved with far fewer casualties, and who in addition wondered, when it was over, about the personal courage of the rescue commander himself. It raised one of the great questions of command in wartime: Does elemental success in a crucial battle excuse all other failures and lapses? And if you succeed, are there are other issues you should answer to?

24. T

ASK

F

ORCE

C

ROMBEZ,

F

EBRUARY

14–15, 1951

On the morning of the fifteenth, Crombez ran into heavy Chinese resistance just south of Koksuri. He had placed his infantrymen on either side of the road, but his progress remained slow. At that moment it was not clear whether his tanks would be able to push through in time. Around noon Crombez received a message from the CP of the Twenty-third (by then under Chiles) saying, “Reach us as soon as possible, in any event, reach us.”

The importance of his mission had repeatedly been made clear to Crombez from the start by his superiors. He was visited by General Moore, the Tenth Corps commander, who told him to be there by evening, and then by General C. D. (known to his peers as Charley Dog, to match Army terminology) Palmer, his rather crusty division commander, and then by Nick Ruffner, the division commander of the besieged unit. All three of them pleaded with him to hurry. “I’ll do it personally,” Crombez promised. Finally, General Palmer landed in his chopper to talk to Crombez, check how things were going, and ask when he might reach Chipyongni—one more unneeded reminder that time was of the essence. “I’ll get there and before dark,” Crombez had assured him. Palmer then lent his chopper to Crombez, who scanned the area and saw that the road was still open but that the hills were full of Chinese. The decision to defend Chipyongni was Ridgway’s, and it was vital to his larger strategy for the war. Thus the pressure on Crombez to get through was immense, each visit or call a reminder of how badly Ridgway wanted this one; it was as if the heat falling on Crombez was a direct extension of the heat coming down level by level from Ridgway to the officers—nothing but brass—immediately below him.

From the moment the battle began, Ridgway seemed to believe that the tide of the war depended on its outcome, that the sooner the Americans and their UN allies showed they could handle the numerical superiority of the Chinese, the more quickly other victories would come. What was at stake was not just a specific small piece of terrain, but the very psyche of his army. If Freeman, and now Chiles, could hold, it would be a symbol to all the other fighting men that they had entered a new phase of the war, one in which the Chinese had been stripped of the immense psychological advantage they had gained at Kunuri. In the months to follow, Ridgway was determined to keep adjusting the battlefield odds, to make things better for the men under his command—better food, warmer clothes, better armaments, better commanders—and to wage a campaign by artillery and air that would turn the lives of the Chinese soldiers into pure misery. But first and foremost he needed to change the mind-set of his own men.

At a certain point, Crombez called Chiles and said he did not think he could get there with his full train of infantrymen and supply trucks and ambulances. “Come on, trains or no trains,” Chiles replied. Then Crombez made a fateful decision, one that would forever after cling to his reputation as a kind of permanent asterisk. He decided to turn his charge to Chipyongni into an armored assault. He would get rid of most of the non-armored part of his column, narrowing it down from three battalions to a much smaller, more streamlined force. He would take his tanks and the engineers—he needed the engineers to remove land mines, for the Chinese used their sappers skillfully. In addition, he would place a company of infantry on top of the tanks, and, less burdened, go all out. What bothered the men who made the rest of the assault, and the historians who wrote about it afterward, was the decision to put the infantrymen on top of the tanks.

To mount on the tanks he chose Love Company, with its 160 men, led by Captain John Barrett. Lieutenant Colonel Edgar Treacy, who had begun the rescue mission as the infantry battalion commander, was appalled by the idea. It violated every aspect of Army doctrine—if the Chinese continued to hit the convoy, the infantrymen riding on the tanks would be sitting ducks for the Chinese machine guns and mortars. Both Treacy and Barrett protested the order—the casualties would be horrendous, they said. Not only were the men on the tanks likely to be exceptionally vulnerable to Chinese fire, but when Patton tanks heated up, they could set a man’s clothes on fire. In addition, the sweep of one of the tanks’ big guns could knock men off at any time. What most men—certainly military historians who wrote about it—believed was that the tanks should have been buttoned up, with perhaps some infantrymen and engineers riding inside protected vehicles that followed behind the tanks. Then they could have gone hell for leather to Chipyongni. At the very least, if the infantrymen got off, there had to be some very dependable means of communication between their commander and the commander of the tanks.

What made the battlefield confrontation between Crombez and Treacy particularly difficult and caused subsequent events to be touched by exceptional bitterness and anger was the fact that there already appeared to be unusually bad feeling between the two of them. Both were West Point men, but theirs had been very different West Points and very different careers after graduation. Crombez had been born in Belgium, had enlisted in the Army in 1919, and had made it to West Point, graduating in 1925. He had always retained a rather heavy accent, and had been seen by his classmates as a heavy-handed striver, too crudely ambitious in terms of the academy’s culture. What had attached itself to Crombez early on was the back-channel word that he wanted it

all too much and yet did not have the right stuff. At the start of World War II, he was sixteen years out of the academy and was, in terms of command possibilities, a little too old for the lower ranking commands and not good enough for the more senior ones. He had done stateside training for most of the war. By war’s end, he had made colonel. Like almost everyone else in the postwar military, his personal position shrank and he became a light colonel.

After the war, he finally got a command, being placed in charge of two separate regiments of the Seventh Infantry Division in Korea. He was, in the vernacular of the Army, something of a hard-ass, a petty one at that, it was believed, someone who seized on small things and made them too important. Before the Korean War started, he seemed disproportionately interested, for example, in keeping the troops stationed near Kaesong away from the hookers in town. Troops being troops, they were going to find a way to connect, even if it meant slipping the women into the barracks, as they sometimes did, disguised as ROK soldiers. Crombez once showed up at a company headquarters and threw a fit because in the little stand where the soldiers could buy some basic needs, the different candy bars for sale were not lined up properly. Still he had managed to hang on and, in 1949, was promoted once again to colonel, this time permanently. When the war started, he was given command of the Fifth Cav. His position, however, was in jeopardy, for Ridgway was eager to replace most of the regimental commanders with younger men. As the oldest of them, Crombez was a prime candidate to be sent somewhere else and thus fall short of getting his star. It was an unenviable situation, one likely to make an already aggressive officer even more so.

By contrast, Lieutenant Colonel Edgar Treacy was as close as you could get to being Crombez’s mirror opposite, a gifted younger commander of virtually the same rank who had graduated from West Point ten years later. He was a kind of golden boy, with admirable connections within the Army’s hierarchy, and yet beloved by the men in his battalion. Whether the bad feelings began because the younger man’s career seemed so effortless, blessed as he was with personal grace and the support of powerful superiors, or because Treacy, as some men believed, had sat on the board that recommended that Crombez be reduced to lieutenant colonel at the end of World War II, no one was sure. But the tension had been apparent since the early days of the Naktong fighting, when Treacy was a battalion commander under Crombez.