The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (83 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

From the start the Chinese believed they could control the road simply by disabling the larger Americans vehicles just as they had below Kunuri. They concentrated their fire on the driver compartments of the big trucks. Their fire was so heavy and so well concentrated that there was no possibility of clearing the road. Most of the big guns would have to be left behind. Fourteen 105s and five 155s were abandoned, along with 120 trucks, some of them carrying wounded. It was in all ways a disaster. Colonel Keith was first listed as missing in action and then as probably having died in a prison camp. Fortunately, the Dutch battalion fighting hard at Hoengsong managed to hold; and the varying forces of the

Thirty-eighth along with some of the artillery men managed to retreat through Hoengsong and back to Wonju. The losses had been devastating: the two battalions along with the Dutch battalion suffered more than two thousand casualties. There were about ten thousand ROK casualties as well. Ridgway, hearing the news, was furious, and soon showed up at Tenth Corps headquarters and gave Almond a ferocious blistering. It was, said Lieutenant Colonel Jack Chiles, who was an Almond deputy at the time, the worst ass-chewing he had ever heard. Ridgway did not yet know of the full casualties in the battle, but he knew how many artillery pieces they had lost, and that in his book was sinful, the loss of big guns to the enemy. There was a great deal of talk about reckless misuse of artillery, and a great deal of emphasis, Chiles said, “

that this will never happen again!

” But for whatever reason—fear of upsetting MacArthur, the incompetence of his other corps commanders—Ridgway did not relieve Almond.

The knowledge that the equivalent of an entire battalion had been lost was brutal enough, but a month later, during another American offensive, some Marines went through the same valley and discovered that the battlefield was littered with American bodies, those of the men of the Thirty-eighth Regiment who had been killed trying to get back to Wonju. Salvage and recovery troops were sent in and recovered more than 250 American and a large number of Dutch bodies, including that of their battalion commander, Marinus den Ouden. Most of the men had multiple bullet wounds—a sign that they had fought to the last and had eventually been overrun. After the war was over and a more careful accounting was done, the regiment’s death toll for the three days of battle was placed at 468. Of that total 255 died on the battlefield and another 213 in captivity. Keith’s Fifteenth Field Artillery Battalion lost 83 men killed that night, and another 128 in Communist prison camps. “Massacre Valley,” the Marines called the area. One Marine posted a sign that reflected, among other things, the bitterness over the nomenclature chosen for the war: “MASSACRE VALLEY/SCENE OF HARRY TRUMAN’S POLICE ACTION/ NICE GOING HARRY.”

THE COMMUNIST SUCCESSES

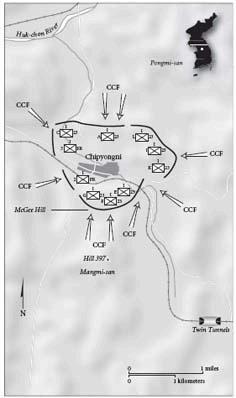

in the central sector were mounting. Three days into what had started as an American offensive, the Chinese were now moving in on two of the prizes they had sought from the start, Wonju and Chipyongni. As the Chinese seemed ready to take Wonju, fears for Chipyongni grew. So far almost everything the Americans had done in Wonju had gone wrong, and the Communist victories had seemed like a continuation of what had happened around the Chongchon. Then, with both Wonju and Chipyongni at stake, the Americans caught a major break, the kind that can turn defeat into victory.

On the morning of February 14, a small artillery spotter plane was flying over the Som River, which cut its way through the mountains northwest of Wonju. One of the observers, Lieutenant Lee Hartell of the Fifteenth Field Artillery Battalion, happened to look out. There, along the sandy beach of the river, was an unusually heavy tree line, or so he thought at first, a lot more trees than one usually saw in that area. He decided to look again. This time he noticed that the tree line was moving. It was not a tree line, he suddenly understood, but a vast Chinese force, seemingly well camouflaged, and so confident that they were moving en masse in daylight as they almost never did, and did not even freeze as they were supposed to when a plane came over. With victory so close and time so precious, they now had too little respect for their enemies and had simply ignored the spotter plane. Hartell and his stunned pilot placed the force at as many as two divisions, perhaps fourteen thousand men moving four abreast, almost surely on their way to the final battle for Wonju. Hartell radioed in his find and called for artillery fire. The battle was soon to be memorialized by the Americans as the Wonju Shoot.

The first round was a white phosphorous marker, and with that, the Wonju Shoot began, as the Americans poured in a brutal barrage of artillery fire on the Chinese. The Americans had massive artillery ready to fire on the Chinese force—some 130 big guns, thirty 155s and one hundred 105s—and a commander, Brigadier General George Stewart, who, though not an artillery officer, knew how to exploit a stunning break like this. If there was one senior officer in the entire corps who stepped forward and acted professionally in the midst of the larger battle of Wonju and Hongchon and Hoengsong, it was Stewart. Among the men of the Second Division he was considered the most rational, professional, thoughtful, and perhaps most important of all, independent senior officer.

Stewart had become the assistant division commander almost by chance. He was someone who had always thought he would be an infantry officer, had graduated from West Point in 1923, but had not managed to get an infantry command. When World War II started, he was too old for a junior command and did not have enough going for him to get a more senior one. Instead he had been given one of those vital assignments no one really wants, but which need to be done and done well. He was made chief of transportation for the Allied forces, first in North Africa, then in Italy, next in the Southwest Pacific, and he was in charge of transportation for the invasion of Japan when the war ended. He had performed brilliantly at his various tasks, an irreplaceable man in two theaters of war. But his abilities worked against his career ambitions. He was too badly needed elsewhere to get the infantry commands he always wanted. He had ended the war as a brigadier general, had been bumped down

to colonel during the demobe, and then promoted back to brigadier in January 1947. He was, thought Ken Hamburger, the soldier, historian, and teacher, “one of those special men the Army produces, talented and brave and thoughtful, all in all an exceptional officer, but not quite ruthless enough to be a great general. The great generals, men like Ridgway, though they are not reckless, know when the moment arrives when you have to risk the lives of your men in the call of duty.” Stewart in 1950 was still doing logistics and had overseen the logistics of the Inchon landing, still longing for that infantry command that was always just out of reach.

In early December, as the Chinese drove south, Stewart was told that—lest the Chinese overrun it—his logistics command would move south to Pusan. He wanted no part of the move. His son, George Stewart, Jr., a 1945 graduate of West Point, was a lieutenant in the 187th Regimental Combat Team. The idea that he would be operating from a safe slot in a safe haven while his son was in harm’s way the elder Stewart found singularly offensive. He visited the Eighth Army chief of staff, Lev Allen, and asked for a different assignment. Allen told him to get on with his assignment and get to Pusan. But on his way out of Allen’s office Stewart ran into Bob McClure, who had just been given command of the Second Division. On a whim, he asked McClure whether he needed a good assistant division commander. Because the then-ADC, Sladen Bradley, was in the hospital, Stewart was given the job, at first on a temporary basis, eventually permanently. His position in the hierarchy was vulnerable, more so after McClure, his sponsor, was so quickly relieved. Stewart had limited authority, more adviser than commander; he was to give no commands on his own. Everything he did had to be cleared with Ruffner, who had replaced McClure, and that meant, in effect, with Almond, who wanted him gone.

Earlier, with Wonju about to be assaulted by Chinese forces, the size of which they were just beginning to comprehend at Corps, Almond had put Stewart in charge of the town’s defense, and he did it in a distinctly Almondesque fashion. He ordered Stewart to Wonju late on the day of February 13, the day before Hartell spotted the two divisions, and left behind for him quite specific instructions on how to fight the battle: “General Almond directs that you take command of all the troops in the vicinity of Wonju, defend and hold that important road junction at all costs. The General believes that the Chinese will attack on your right,

BUT THE DECISION IS YOURS.

The General believes you should place the one intact BN of the 38th on the line,

BUT THE DECISION IS YOURS.”

Then, having passed on the orders, the G-3, as Stewart noted, immediately departed the endangered post.

The instructions, Stewart decided, were completely worthless. He had studied the terrain and, with the limited intelligence he had, decided the attack

would come from the left—in this he was correct—and so he held in reserve the one good battalion of the Thirty-eighth that remained. Though he was an infantry officer and not an artillery man, he was exceptionally knowledgeable about the uses of artillery because of some cross training he had done in the 1930s. Now, with a relatively small defensive force under his command and perhaps as many as four divisions on the attack, he knew he was going to need all the expertise in big guns that he could muster, and he was shrewd enough not to count on any help from Loyal Haynes, the division artillery commander, whom he, like many other men, considered an exceptionally weak officer. Upon arrival, even before the battle started, he ordered Haynes to have his men prepare data so that they could fire on critical points of approach upon command; he wanted map overlays prepared that could allow his artillery to hit different points simply by using a preselected number. In effect, he wanted to be able to call in massive fire instantaneously without any calculation in the middle of battle. No time was to be wasted.

Thus, when Hartell first spotted the Chinese, Stewart and his guns were ready. Catching a giant Chinese force in the open with so many artillery tubes at his disposal, he intended to maximize his advantage. On several occasions that day Haynes tried to slow Stewart down, but he was ignored. With Lieutenant Hartell still able to fly over the scene and call in adjustments, the artillery men very systematically poured shell after shell on the Chinese. And yet the Chinese kept coming. Nothing, it seemed, could stop them, not even this merciless hail of fire. For this was one of their great weaknesses at that point in the war: once a battle was initiated, they had little ability to make adjustments. So the artillery shoot went on for more than three hours. At one point Haynes asked Stewart to stop because they were running low on ammo—but Stewart, knowing this was a chance he might never have again, waved him off. “Keep firing until the last shell is used,” he said. He then ordered up an immediate ammo resupply from Japan. It was, as J. D. Coleman pointed out, in its logistics a stunning symbol of a most unlikely American advantage. Additional artillery shells could arrive for the Wonju garrison in hours—whereas for the Chinese it often took several days or more to get more ammunition to a battle. A little later Haynes called Stewart to insist that they had to slow down because his guns were overheating. Again Stewart paid no attention. “Keep firing until the gun barrels melt,” he ordered.

It was the turning point in the battle. An estimated five thousand Chinese were killed and thousands more wounded. Though there was more hard fighting to come, Wonju had been saved. The Chinese losses in the central corridor were monstrous, possibly as high as twenty thousand killed and wounded. At the command level there was no doubt that Stewart was the hero of the battle,

though Almond, he eventually noted, seemed quite unappreciative. Late in the afternoon, when the artillery shoot was over, Brigadier General William Bowen, the commander of the 187th RCT, arrived at Wonju CP headquarters, and Stewart was ordered rather peremptorily to return to Division headquarters. (“Corps felt my presence was no longer necessary,” he dryly noted.) Almond awarded Bowen a Silver Star for his part in the battle but awarded nothing to Stewart. Honoring him, after all, would mean that Stewart had correctly reversed Almond’s own erroneous instructions on how to fight, and more important, that he was a worthy ADC and would henceforth have to be taken seriously in the division hierarchy.

Though the Chinese offensive had been blunted at Wonju, Chipyongni still stood exposed.

L

IEUTENANT PAUL MCGEE

of Belmont, North Carolina, had finally gotten his first real taste of combat when George Company of the Second Battalion of the Twenty-third Infantry Regiment relieved a French company on the top of the ridge at Twin Tunnels. McGee commanded George Company’s Third Platoon. It had taken long enough—he had tried to join the Marines on December 8, 1941, when he was seventeen, but had been rejected by the Corps because he was color-blind. His subsequent service in World War II had somehow disappointed him. Only when he and his men climbed the hill at Twin Tunnels to relieve the French was McGee struck by how brutal war truly was, and how callous it seemed to make the men who did the fighting. George Company had arrived after the fight was over, just in time to survey the carnage of a terribly hard-fought battle. McGee could understand much of the battle just by letting his eyes follow the trail of Chinese bodies, hundreds of them it seemed, representing the early waves of the enemy’s assault, corpses that were now frozen, fixed permanently in the final moments of their lives. It was as if he had discovered a giant, open-faced Chinese burial ground. As he and his men climbed the hill, it only got worse: French soldiers were coming down, carrying their dead on a path so narrow they had no choice but to descend single file, two-man teams hauling out the dead, using the most primitive kinds of slings, the body being dragged on the ground on a rope between two men.

What struck McGee was how casual the living seemed about what they were doing, how immune to death they were. The French soldiers were talking—laughing, sometimes—as if nothing had happened, and yet the bodies they were carrying had been their buddies just the day before. There was no sign of mourning. He wondered if the French were different from American soldiers, or whether this was part of the secret ritual of survival, known only to other combat troops who had made it through their own small hells, because if you thought about it too much, you could no longer function. McGee pondered that again at the top of the ridge, where the French position had been.

The word was that the French tended to dig deeper foxholes than the Americans, but because of the rocks and the ice, their holes were not very impressive, in some places just a couple of inches deep, and everywhere on the ground was blood; in some cases, brains spilled out. For the first time McGee wondered what he had gotten himself into.

Well, he had done it all by himself. He had chosen this place, had volunteered to go to Korea, and worse had pushed to be with the frontline troops, thereby violating the most basic law of the Army, which was never to volunteer for anything. Truth be told, he had not merely volunteered, but had systematically pressured the Army to give him his own rifle platoon. He had forced the Army to pluck him from the job it greatly preferred for him—as an instructor back at Fort Benning, Georgia, training other young men to go to Korea—and to send him all the way here instead. Now, ten days after that first jarring view of the carnage of battle at Twin Tunnels, he was at Chipyongni, waiting patiently in his foxhole on the south side of the perimeter, guarding the sector that would turn out to be the most vulnerable part of Paul Freeman’s regimental defense.

McGee was a country boy from rural North Carolina, and he had wanted to serve his country for a long time. After the Marines turned him down, he had joined the Army and waited patiently in England to cross the Channel for his chance at battle. He was not in on D-day or anything else that mattered in the subsequent weeks. He envied those who, to his way of thinking, were luckier. Instead his unit, the Sixty-sixth, or Black Panther Division, was held in reserve. Then, during the Battle of the Bulge, it had been chosen to go in with the Third Army and reinforce the embattled troops near Bastogne, and McGee had been pleased. But during the Channel crossing, a German U-boat hit a transport carrying one of the division’s other regiments, and 802 men went down with the ship. Because of that, they had pulled McGee’s division and regiment back and finally sent it to another area, near St. Nazarre, where its job was to keep German units guarding sub bases bottled up. That had seemed more like police work than combat, and when the war was over, McGee wondered if he would ever get his chance. He was too young to realize that, for those eager enough, there was always going to be enough war to go around.

McGee had returned to North Carolina, and stayed out of the service for about a year and a half before joining the reserves. He and his older brother Tom, with whom he was very close, were running a small grocery store and filling station in the Belmont area, and there was one Army recruiting sergeant whom they liked and who had them marked down as possible enlistees. The McGee filling station and store was not a stunning financial success. People were moving from the country to the city and suburbs, and the store was

already beginning to run on credit. So the sergeant kept coming by and selling them the virtues of the Army in a time of peace—the chance to see the world, without the likelihood of ever having to fight for their country. Finally the McGee brothers, Paul and Tom, agreed to re-up if they could choose their area, pick their unit, and serve together. The sergeant said that would be just fine. They picked the Far East because they had already been to Europe, and Asia sounded much more exotic. They got what they wanted—Japan and the Seventh Infantry Division, Paul in Able Company, Tom in Baker Company of the Seventeenth Regiment. Paul McGee was surprised by how much he liked the Japanese people, who were friendly, and Japanese women, who were even friendlier in those days, because when he had been fighting in Europe he had not hated the Germans, but for some reason he did not understand at the time he

had

hated the Japanese.

Japan had turned out to be good duty. The only thing that had bothered McGee was the terrible shape the Army was in. He remembered one cold, rainy day when he was giving a training lesson on how to set up a combat outpost. General Walton Walker came by, complimented him on the job he was doing, and told the assembled GIs to pay attention to this fine young soldier who knew something about warfare, because sooner or later they were going to be in a war. Then Walker asked McGee if he wanted to be an officer. That was an interesting question because McGee was already an officer in the Army reserve, but as an active soldier he was only a sergeant with two rockers. He had been wary of becoming a regular Army officer because in his mind they were mostly West Point men, or college graduates anyway, and he did not think that a country boy with a shaky tenth-grade education would stack up well against them. Then Walker asked if McGee would be interested in Officer Candidate School (OCS), and that seemed like a better idea. He said yes, but only if his brother Tom could come along. Walker thought it could be done. So both McGees filled out their papers, but it turned out you had to be at least a sergeant for OCS, and Tom McGee was a mere corporal. So only Paul McGee ended up at OCS after all.

When the Korean War started, Paul, back in the States, could not wait to get over there. He immediately volunteered to go, but the Army, ever the contrarian force, held him at Fort Benning, while his brother, with the Seventh Division, was cut off near the Chosin Reservoir in late November. That made him want to go more than ever; he was sure Tom needed him, even after he was one of the lucky ones who made it back from the Chosin. In time the Army decided that it

did

need Paul in Korea, and that he

was

an officer, not an enlisted man, and since platoon leaders were in great demand, they shipped him out. He was assigned to the Second Division and managed to

con people into putting him in the Twenty-third Regiment because it was closest to Tom’s Seventeenth Regiment in the Seventh Division, which was also part of Tenth Corps. He had gotten up to the Twenty-third Regiment in January and was immediately sent to the Second Battalion. The people at Battalion were so happy to see him that they offered him the heavy-weapons platoon, filled as it was with mortars and machine guns. Instead he asked for a rifle platoon in George Company because that was the unit nearest to his brother’s regiment.

The people at the Second Battalion headquarters thought he was a lunatic. “McGee, you’re crazier than hell,” one of the officers said. “We’re losing platoon leaders in our rifle companies every day. But the heavy weapons platoon—that’s another thing. That’s the best deal we’ve got. You’re surrounded by all that firepower, and they’re about three or four hundred feet back from the front line where the other troops are.” No, McGee replied, he knew all that, but he wanted to be up on the line, wanted to command nothing but men who really wanted to fight under him, and he wanted to be as close as he could to the Seventeenth Regiment. That first night he got word to his brother, and Tom drove right over in a jeep to see him. “What the hell are you doing here?” Tom McGee asked. “I came out here to get you out of this goddamn place,” Paul McGee said. “Boy,” answered Tom, “you’re really going to be sorry. People are getting killed here every day—you should have stayed back home.” So it was that Paul McGee had taken command of the Third Platoon of George Company, whose perimeter at Chipyongni was approximately five hundred yards long—the equivalent of five football fields.

Waiting up there on the line, he knew the time was coming close when the Chinese were going to hit. He had been on several patrols, and enemy activity had increased dramatically every day, while the range of the patrols had shortened accordingly. He had also heard through the rumor mill that any attempt to withdraw from the village had been rejected. That guaranteed that they were going to stay and fight. He was finally going to get his chance. On February 13, the word was that the Chinese were likely to come that night.

George Company’s position was hardly ideal. It jutted farther out than the rest of the defensive positions and lacked the elevation of most of the other UN defensive points. It faced Hill 397, and they knew there were Chinese there. In fact, it was as if there were a ridge that emerged from the George Company position and virtually connected it with Hill 397, almost, as Ken Hamburger noted, like a finger extending from their position to the Chinese position. That gave the Chinese a natural approach to McGee’s platoon. As he waited for the battle to start, Paul McGee had no idea that his sector would prove to be the most bitterly contested in the entire battle, or that his battalion commander, Lieutenant Colo

nel Jim Edwards, would in his after-action reports name this small part of the larger perimeter McGee Hill.

McGee had a total of forty-six men in his platoon. They seemed like good men, but he had no way of really knowing, because he had never fought with them before. He had made sure their foxholes were adequately deep—four feet at least. His own was just fine, four feet wide, six feet long, and about six feet deep, with a firing step that allowed him to duck when he wanted to, and fire back when he was ready. But, regrettably he thought, theirs was an oddly barren hill. There was no way to create any kind of cover around their foxholes—no logs, no debris of any sort. That made it possible for attacking troops to lob grenades in. Worse yet, although a good deal of barbed wire had gone up around the greater Twenty-third perimeter, they had run out of it before reaching George Company. There had been just enough to place a double apron in front of George’s First Platoon, but none in front of McGee’s position. At that moment, whatever Division and Corps could spare, whether it was airpower or barbed wire, went to Wonju.

If McGee was unhappy about this critical shortfall, he accepted it as well. That was the deal and soldiers were meant to accept the deal. If it had been a perfect battle in a perfect world, they would have had enough of everything, not just barbed wire, but logs to protect the foxholes, and enough mines, and a hell of a lot better communications. But it was not a perfect battle in a perfect world—it was going to be a difficult battle in a godforsaken place—most battles were. Some of the regiment’s engineers came and helped create two fougasse bombs, taking fifty-five-gallon drums, filling them with a mixture of napalm and oil, in addition to what they hoped was a reliable ignition system, all in a lethal homemade mine, which they then buried. It was a potentially devastating weapon; each fougasse might take a lot of Chinese with it, but as a one-time weapon it was no substitute for barbed wire. As it happened, neither fougasse went off—perhaps the engineers had not done the ignition system right, McGee thought. They also created some other homemade mines, taking some hand grenades, pulling their pins, but keeping the ignition suppressed inside a ration can and running lines to them so that when the lines were jerked, the grenades would explode.

The Chinese hit first, as expected, on the night of the thirteenth. McGee heard the bugles around 10

P.M.

Then they started coming—and just kept coming and coming. Some people had said they would come in human waves, but that was not quite right, unless you thought of a very small wave, and then a slightly bigger one each time, as if the attack was first a squad, then a platoon, then a company. They were clearly looking for the American positions and marking them, wasting if need be a good many lives in the process. The first night, McGee thought, went quite well. He had ordered his men not to fire on sound, but only when they actually saw the enemy, in order to conserve ammunition. When dawn came, there were stacks of Chinese bodies sprawled around the position, but no one had penetrated it, and McGee had lost no men.