The Book of the Poppy (5 page)

Read The Book of the Poppy Online

Authors: Chris McNab

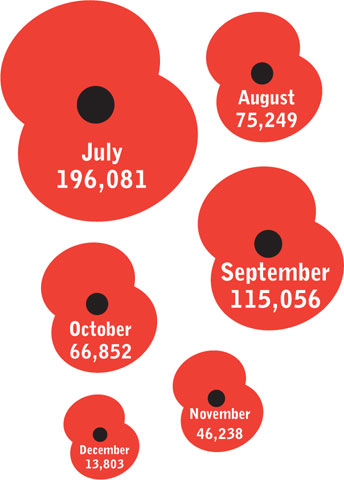

GROSS TONNAGE OF BRITISH VESSELS LOST TO U-BOATS, 1914–18

FRONTLINE VOICES:

THE BATTLE OF PASSCHENDAELE

The journalist Philip Gibbs, present on the Passchendaele battlefield, attempted to describe the landscape of death they faced:

Every man of ours who fought on the way to Passchendaele agreed that those battles in Flanders were the most awful, the most bloody, and the most hellish. The condition of the ground, out from Ypres and beyond the Menin Gate, was partly the cause of the misery and the filth. Heavy rains fell, and made one great bog in which every shell crater was a deep pool. There were thousands of shell craters. Our guns had made them, and German gunfire, slashing our troops, made thousands more, linking them together so that they were like lakes in some places, filled with slimy water and dead bodies. Our infantry had to advance heavily laden with their kit, and with arms and hand-grenades and entrenching tools – like pack animals – along slimy duckboards on which it was hard to keep a footing, especially at night when the battalions were moved under cover of darkness.

You live for days in the closest contact with your comrades in a contracted space. You cannot move, and are unable to think clearly. Never did I realize how difficult it can be to lead a human life. There is nameless agony in it.

Philip Gibbs,

Adventures in Journalism

, 1923

The Battle of Passchendaele resonates in the imagination even today, as it presents a picture of normally picturesque Flanders transformed into a hell on earth. Yet as many soldiers noticed, in Flanders and in other regions of the blasted frontline, nature had still not given up on the land.

Papaver rhoeas

is known by many other common names – corn poppy, corn rose, field poppy, red poppy and red weed. The last name on the list here is revealing, for although this member of the poppy family produces a beautiful vivid red flower, it is nonetheless classified as a weed. It grows in the most ravaged and inhospitable of land (indeed it thrives best in soil that has been disturbed), hence it managed to add a haunting dash of colour to the shell-thrashed landscape of Flanders in the late spring, summer and early autumn each year. Another of its common names is the Flanders Poppy.

To see such beautiful flowers growing across fields that were already sown with the bodies of thousands of dead men must have left an impression on the minds of all who witnessed it, the flowers delivering a curiously mixed evocation of the red blood of the fallen yet the regeneration of new life. One man who was certainly captured by the vision was the Canadian soldier Lieutenant-Colonel John Alexander McCrae.

‘IN FLANDERS FIELDS’

McCrae was born on 30 November 1872, and went on to combine strong careers in both medicine and soldiering. He served as an artilleryman during the Boer War, after which he worked as a physician and pathologist at several hospitals, including the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Infectious Diseases. He also co-authored a medical textbook:

A Text-Book of Pathology for Students of Medicine

, published in 1912. A man with an adventurous mindset, McCrae became a field surgeon with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) and British forces on the Western Front in the First World War. During this service, he managed a field hospital taking in casualties from the Second Battle of Ypres, a job requiring the utmost strength of character to endure mentally. In a letter to his mother he remembered:

For seventeen days and seventeen nights none of us have had our clothes off, nor our boots even, except occasionally. In all that time while I was awake, gunfire and rifle fire never ceased for sixty seconds … And behind it all was the constant background of the sights of the dead, the wounded, the maimed, and a terrible anxiety lest the line should give way.

McCrae also suffered personal loss during the battle – his friend and his former student Lieutenant Alexis Helmer was killed in action. McCrae conducted the burial service himself, but during this time he also noticed the red poppies growing obstinately through-out the Flanders landscape. Being a man of literary talents, the poppies and his dead friend began to stir a poetic vision that would move generations to come.

The origins of McCrae’s poem ‘In Flanders Fields’ are uncertain, in terms of when and where he first composed it, but he became convinced of its merit and spent several months working it into shape. He eventually submitted it to

The Spectator

magazine, but it was rejected. Yet his next submission, to the redoubtable

Punch

, was accepted, and it was published on 8 December 1915. Here is the poem in full:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

The poem manages to walk that fine line between patriotism and grief, mourning and resilience. The opening image, of the poppies scattered amongst the graves, seems to hold out promise of some beauty in a dark world, although the statement ‘We are the Dead’ at the beginning of the second stanza has a disturbing, blunt effect. By the end of poem, the poppy and the dead are inextricably intertwined, as if the flower makes visible the absence of the fallen.

‘In Flanders Fields’ had an enormous effect on the reading public. It was translated into dozens of languages and achieved global distribution. The poem was applied in political campaigns in Canada, and was given out as encouragement to British and, later, US soldiers fighting on the Western Front. It was also utilised persuasively in campaigns to get the public to purchase war bonds. More importantly, such was the power of the poem that it endured the war years to become a staple classic of the particular genre known as ‘war poetry’. (As the author was writing this book, even his teenage daughter instantly recognised the poem when she caught a glance of it on the screen.)

Not everyone has been impressed with ‘In Flanders Fields’. The patriotism it contains, especially in the last stanza, often strikes as jingoism to the modern ear, a tool for recruiting more men and sending them to the grinding mill of the Western Front. Yet for the purposes of our narrative here, one effect is key – it began the development of the Remembrance Poppy.

MOINA MICHAEL AND THE CREATION OF THE POPPY

Born in Good Hope, Georgia, USA, on 15 August 1869, Moina Belle Michael may seem an unlikely figure to intersect with our narrative of the Remembrance Poppy. She was a highly educated woman, and by the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914 she was a professor at the University of Georgia.

Michael was also a passionate humanitarian, and as the war progressed she devoted more of her time to working for the Young Women’s Christian Association, helping to ready workers for overseas service. In her autobiography,

The Miracle Flower: The Story of the Flanders Fields Memorial Poppy

(1941), Michael explained how, when in New York City on 9 November 1918, with the Armistice just two days away, she came across McCrae’s poem (then titled ‘We Shall Not Sleep’)

in the

Ladies’ Home Journal

. As she recounts, the emotional effect of the poem upon her was considerable:

BRITISH CASUALTIES ON THE WESTERN FRONT, JULY–DECEMBER 1916

I read the poem, which I had read many times previously, and studied its graphic picturization. The last verse transfixed me — ‘To you from failing hands we throw the Torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die, we shall not sleep, though poppies grow in Flanders Fields’.

This was for me a full spiritual experience. It seemed as though the silent voices again were vocal, whispering, in sighs of anxiety unto anguish, ‘To you from failing hands we throw the Torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die we shall not sleep, though poppies grow in Flanders Fields’.

Alone, again, in a high moment of white resolve I pledged to KEEP THE FAITH and always to wear a red poppy of Flanders Fields as a sign of remembrance and the emblem of ‘keeping the faith with all who died’.

In hectic times as were those times, great emotional impacts may be obliterated by succeeding greater ones. So I felt impelled to make note of my pledge. I reached for a used yellow envelope, turned the blank side up and hastily scribbled my pledge to keep the faith with all who died.

Moina Michael,

The Miracle Flower: The Story of the Flanders Fields Memorial Poppy

, 1941

In this vivid moment, Michael crystallised the idea for the Remembrance Poppy. (McCrae himself was no longer alive by this time – he had died of pneumonia on 28 January 1918.) She quickly went out and acquired all the artificial red poppies she could find in the Wanamaker’s department store, and began to sell them. It was the beginning of a concerted campaign to make the poppy a national commemorative symbol. Her vision was for a single national motif, albeit one that could be reproduced in various different forms, to act as a reminder of all those lost in the war. In December 1918 she worked with a designer, Lee Keedick, who helped her produce a final motif. It featured a poppy, coloured with all the hues of the Allied flags, intertwined with a Torch of Liberty. With this design in hand, Michael strode on tirelessly, pushing for national adoption, but two years of effort did not seem to advance her cause significantly.

Then came a breakthrough. In August 1920, Michael convinced the Georgia Department of the American Legion (a US veterans’ organisation) to adopt the Memorial Poppy as its symbol, albeit without the Torch of Liberty motif. This in turn, at the National American Legion convention in Cleveland on 29 September 1920, led to the Memorial Poppy being adopted as a country-wide symbol of remembrance, with the idea that American Legion members and supportive members of the public would wear the poppy annually on Armistice Day, 11 November. Michael had achieved her goal, but now the Memorial Poppy was about to spread internationally.

‘WE SHALL KEEP THE FAITH’

Moina Michael wrote ‘We Shall Keep the Faith’ in response to her reading of McCrae’s ‘We Shall Not Sleep’/‘In Flanders Fields’:

Oh! you who sleep in Flanders Fields,

Sleep sweet – to rise anew!

We caught the torch you threw

And holding high, we keep the Faith

With All who died.

We cherish, too, the poppy red

That grows on fields where valor led;

It seems to signal to the skies

That blood of heroes never dies,

But lends a lustre to the red

Of the flower that blooms above the dead

In Flanders Fields.

And now the Torch and Poppy Red

We wear in honor of our dead.

Fear not that ye have died for naught;

We’ll teach the lesson that ye wrought

In Flanders Fields.

In Flanders Fields we fought.

Moina Michael