The Book of the Poppy (8 page)

Read The Book of the Poppy Online

Authors: Chris McNab

WAR GRAVES

Even today, after a century of time has passed, the battlefields of the First World War keep relinquishing the dead. In 2007–08, for example, mass burial pits that had lain undisturbed for ninety years were discovered on the outskirts of Fromelles in northern France. They contained the bodies of 250 Commonwealth soldiers (mostly Australians) who had been killed in the Battle of Fromelles (a subsidiary operation to the Battle of the Somme) on 19 July 1916, and were subsequently buried by the Germans in communal graves.

Upon the discovery of the bodies, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) began attempting to identify the dead, analysing the surviving artefacts around the bodies and using modern DNA analysis techniques. Ultimately, the bodies consisted of 205 Australians (ninety-six of whom the CWGC identified by name) plus three British soldiers and the rest ‘unknowns’. A special cemetery was constructed in 2009–10, known as the Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery, and the bodies were eventually laid to rest with full military honours.

Military cemeteries are unique places of remembrance. Some are relatively small, tucked away in distant locations. The Gravesend Military Cemetery in Bridgetown, Barbados, for example, is a CWGC cemetery containing the bodies of just nine individuals, all killed in action between 1942 and 1944. At the other end of the extreme are the huge, almost disorientating cemeteries and memorials in Western Europe, of which the following are representative. The Fricourt German War Cemetery contains the bodies of 17,027 German soldiers, while the Douamont Ossuary on the Verdun battlefield site contains the bones of more than 130,000 unidentified soldiers, the remains taken from the devastating battle of 1916. The Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial, the largest American burial site in Europe, has 14,246 graves spread over 130 acres (52 hectares). The huge Thiepval Memorial to the Missing displays the names of 73,357 British and Allied soldiers who died in the Somme area between 1916 and 1918, but who have no official grave.

The cemeteries and memorials listed are just a handful from one particular conflict. In fact, there are thousands of military cemeteries around the world, some kept with a military eye for cleanliness and detail, others neglected and forgotten beneath overgrown foliage. For the British and Commonwealth countries, the job of maintaining the war cemeteries falls to the CWGC.

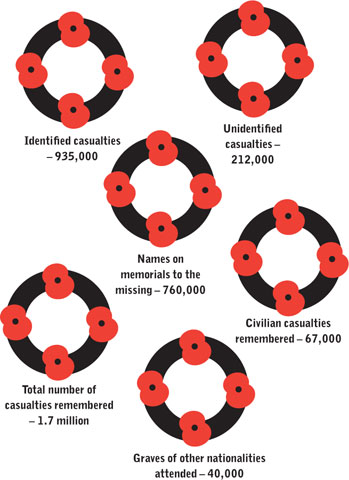

COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION – KEY FACTS

The CWGC was the vision of one man, Sir Fabian Ware, who during the First World War was the commander of a mobile unit of the British Red Cross. Seeing at first hand the levels of casualties, and noting the frequently chaotic processes of burial and body identification, he established the Graves Registration Commission, which received a royal charter in May 1917 to become the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC), and subsequently the CWGC.

In the aftermath of the Armistice, the Commission set about trying to identify the dead, record their details and rationalise the system of cemeteries. By the end of 1918 they had identified 587,000 graves, plus named 559,000 individuals who had no known grave. This was just the beginning of the CWGC’s work. Today the organisation cares for cemeteries, graves and memorials in 153 countries around the world, at a total of 23,000 locations. The number of war dead represented through this critical work now totals 1.7 million. The guiding principles of the CWGC in all this work are as follows:

![]() Each of the dead should be commemorated by a name on the headstone or memorial

Each of the dead should be commemorated by a name on the headstone or memorial

![]() Headstones and memorials should be permanent

Headstones and memorials should be permanent

![]() Headstones should be uniform

Headstones should be uniform

![]() There should be no distinction made on account of military or civil rank, race or creed.

There should be no distinction made on account of military or civil rank, race or creed.

The two central themes of this list are ‘permanence’ and ‘equality’. Unlike the military memorials of centuries past, the CWGC cemeteries and memorials recognise that all the soldiers who died deserve enduring respect, regardless of rank or position.

TOMB OF THE UNKNOWN SOLDIER

One of the many tragedies of the First World War was that so many of the war dead found no permanent grave. Many were hastily buried in crude holes cut into active battlefields, and their rudimentary grave markers were subsequently lost or destroyed in the confusion of action. Thousands were buried in communal graves, their identities often lost in the mass of humanity they lay amongst. Others simply went ‘missing’, many destroyed beyond recognition by high explosive.

For the families of these men and women, the tragedy of their loss was compounded by the complete absence of a grave over which to mourn. This truth was recognised by one Reverend David Railton, a British clergyman serving on the Western Front in 1916, but in a back garden at Armentieres, France, he saw a possible solution. There stood a crude cross bearing the simple words ‘An Unknown British Soldier’. The sight left an impression on Railton, and in 1920, with the war over, he wrote to the Dean of Westminster Abbey, Herby Ryle, suggesting that a single tomb be established in the Abbey containing the body of one unidentified British soldier. Thus placed, the soldier would serve almost as the national representative for all the missing and unidentified dead.

REMEMBERING THE UNKNOWN SOLDIER

Below is part of the eulogy delivered by the Australian Prime Minister, Paul Keating, at the funeral service of the Unknown Australian Soldier, 11 November 1993:

We do not know this Australian’s name and we never will. We do not know his rank or his battalion. We do not know where he was born, nor precisely how and when he died. We do not know where in Australia he had made his home or when he left it for the battlefields of Europe. We do not know his age or his circumstances – whether he was from the city or the bush; what occupation he left to become a soldier; what religion, if he had a religion; if he was married or single. We do not know who loved him or whom he loved. If he had children we do not know who they are. His family is lost to us as he was lost to them. We will never know who this Australian was.

Yet he has always been among those whom we have honoured. We know that he was one of the 45,000 Australians who died on the Western Front. One of the 416,000 Australians who volunteered for service in the First World War. One of the 324,000 Australians who served overseas in that war and one of the 60,000 Australians who died on foreign soil. One of the 100,000 Australians who have died in wars this century.

He is all of them. And he is one of us.

The suggestion (which had also been made by the

Daily Express

newspaper) was adopted by the British Government, and plans for the internment were made. However, there was the sensitive issue of how to select the body. The solution was to gather a number of unidentified remains from various former battlefields and place them on stretchers in a chapel at Saint-Pol-sur-Ternoise near Arras, on the night of 7 November 1920. Two officers, Brigadier-General L.J. Wyatt and Lieutenant-Colonel E.A.S. Gell of the Directorate of Graves Registration, later visited the chapel alone, where Brigadier-General Wyatt selected one of the bodies simply by placing his hand on it. This process was followed to ensure that considerations of rank, birth, politics and other factors did not feature in the selection.

The journey of the body to its final resting place in Westminster Abbey on 11 November 1920 was a humbling sight, the casket drawn through the streets of London on a horse-drawn gun carriage, thousands of onlookers completely silent at its passage. It stopped before the Cenotaph, which then received its unveiling, before journeying on to the Abbey, where the casket was interred in the far western end of the nave, buried in soil actually brought from the battlefields. At the same time, an unknown soldier was buried at the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, the French also making this unique act of remembrance.

INSCRIPTION ON THE TOMB OF THE UNKNOWN WARRIOR, WESTMINSTER ABBEY

BENEATH THIS STONE RESTS THE BODY

OF A BRITISH WARRIOR

UNKNOWN BY NAME OR RANK

BROUGHT FROM FRANCE TO LIE AMONG

THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS OF THE LAND

AND BURIED HERE ON ARMISTICE DAY

11 NOV: 1920, IN THE PRESENCE OF

HIS MAJESTY KING GEORGE V

HIS MINISTERS OF STATE

THE CHIEFS OF HIS FORCES

AND A VAST CONCOURSE OF THE NATION

THUS ARE COMMEMORATED THE MANY

MULTITUDES WHO DURING THE GREAT

WAR OF 1914–1918 GAVE THE MOST THAT

MAN CAN GIVE LIFE ITSELF

FOR GOD

FOR KING AND COUNTRY

FOR LOVED ONES HOME AND EMPIRE

FOR THE SACRED CAUSE OF JUSTICE AND

THE FREEDOM OF THE WORLD

THEY BURIED HIM AMONG THE KINGS BECAUSE HE

HAD DONE GOOD TOWARD GOD AND TOWARD

HIS HOUSE

Many countries around the world now have their own Tomb of the Unknown Warrior. Through graves, tombs, memorials and other means, including the Remembrance Poppy, societies have done their utmost to ensure that the thousands of men and women killed in conflict are remembered, no matter how isolated, terrified or forgotten the individual was on the day of death.

SECOND WORLD WAR LIFE EXPECTANCIES (WORST-CASE SCENARIOS)