The Book of the Poppy (2 page)

Read The Book of the Poppy Online

Authors: Chris McNab

Britain, however, still relied heavily on private soldiers and militias to fulfil its military obligations. For many years India was governed with the assistance of the private armies of the East India Company (EIC), and even during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars the British forces were heavily reliant upon various volunteer, yeomanry (volunteer cavalry) and militia defence forces. Only in the early twentieth century was the situation given a greater degree of order through Haldane’s Territorial and Reserve Forces Act of 1907, which organised non-State units into the Territorial Force. The Territorial Force eventually became what we know today as the Territorial Army, and this critical reserve force has served with distinction in most major British conflicts from the First World War to the present day.

Britain entered the twentieth century with a historically battle-proven army, one that really did ‘punch above its weight’ on the world stage. It was disciplined, professional and experienced, although there were cracks in the veneer. The Crimean War (1853–56), Anglo-Zulu War (1879) and Boer Wars (1880–81, 1899–1902) had shown that while the British could still win wars, they could also suffer disastrous localised defeats if they underestimated their enemies, were led badly or miscalculated their logistical requirements. In Afghanistan in 1842, the British suffered a catastrophe when Afghan tribesmen massacred 4,500 soldiers and 12,000 camp followers, as the vast column attempted to make its escape from Kabul to Jalalabad. At the Battle of Isandlwana in South Africa on 22 January 1879, a Zulu army of 20,000 warriors destroyed an entire British force – 1,300 British soldiers died, despite having modern rifles and artillery pieces at their disposal. During the Boer War, on 23–24 January 1900, a force of Boer warriors trapped hundreds of British troops atop Spion Kop, a hill 24 miles (38km) west-south-west of Ladysmith. Over the course of a horrifying day, 243 soldiers were killed and 1,250 wounded, the hapless British trying to claw their way into solid rock to escape the merciless rifle fire. Such battles, although long distant from our present age, and fought for causes largely alien to our modern politics, still deserve to be remembered for the young men who lost their lives, on days too awful to imagine.

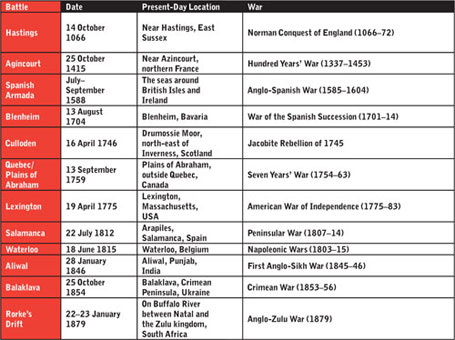

MAJOR BATTLES IN BRITISH HISTORY, 1066–1900

THE ‘GREAT WAR’

As this book is published, the world is preparing to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the First World War. Despite its increasing historical distance, the war has a special resonance in the collective memory. Why is this so? Britain, as we have seen, has a martial tradition stretching back to ancient times, and has fought numerous consuming conflicts on foreign and domestic soils. Yet our reflections upon, say, British participation in the Seven Years’ War or even the Napoleonic Wars are now far more to do with historical interest than national remembrance. The obvious reason for our ongoing connection with the First World War is its proximity. A hundred years is a long time, but there is still a generation of people alive whose parents and grandparents fought in the ‘Great War’. The First World War was also the first recognisably ‘modern’ conflict, a clash wrought across the full spectrum of environments – air, land and sea – and with the same fundamental types of weaponry that dominate conflict today. There is also a political factor – debates over whether the First World War was a ‘justified’ conflict continue to rage, especially as the political repercussions and imperial engineering of the war are still felt around the globe today, particularly in the Middle East and the Balkans. Yet above all these reasons, and the true focus of the centennial commemorations, is the daunting human cost of the war, not only for the British, but also for all those nations who fought.

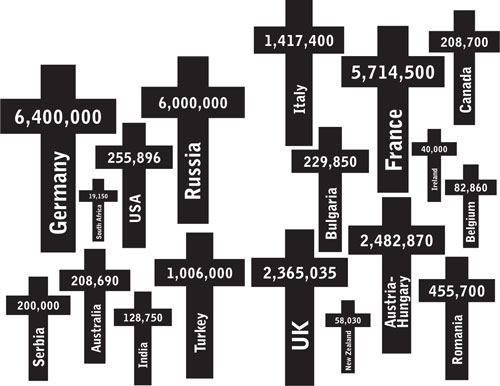

We start with some basic statistics to gain perspective. During the First World War, the United Kingdom had a population of just over 46 million people. Of this number, a total of 5.7 million men served in the armed forces, and within this figure around 700,000 were killed. Add to that grim total an estimated 1.6 million wounded, and some 2.3 million men – nearly half of all those who served in the war – became casualties. Yet this is not including the men and women of the British colonies and dominions (primarily Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa and India), without whom Britain would have been unable to sustain many campaigns. If we add their contribution, the total figure for dead, missing and wounded amongst ‘British’ troops climbs to nearly 3 million.

These figures are stunning enough, but they represent the fallen of just a few of the combatant countries. Looking on the Entente side, France suffered a generational disaster in the form of nearly 1.4 million war dead, plus 4.3 million wounded. Russia’s losses, to our best estimate, were 1.8 million dead and nearly 5 million wounded. It also experienced some 2 million civilian dead. (The civilian death tolls for Britain and France were 1,386 and 40,000 respectively.) Italy took 1.4 million casualties, of whom 462,000 were fatalities.

Figures for the Central Powers are just as dizzying and depressing. Germany lost at least 2 million of its soldiers in fighting on two fronts, plus 5.7 million military wounded and 700,000 civilian deaths. Austria-Hungary suffered nearly 3 million dead and wounded; 478,000 POWs also died in captivity. Turkey’s casualty lists are grossly skewed towards civilian deaths – around 2 million, mainly Armenians caught by the genocide unleashed upon them from

c

. 1915, but also took a million military dead and wounded. When such figures and the rolls of honour of all other combatant nations are added together, the First World War cost the lives of at least 16 million people, with another 20 million wounded.

Few engagements represent the catastrophe of the First World War better than the Battle of the Somme, the British offensive fought between 1 July and 13 November 1916. On the first day of the attack alone, the British suffered 60,000 casualties, including 19,240 dead, despite the confidence that a week-long, 1.6-million-shell bombardment of the German lines would have rendered all the defenders either dead, wounded or insensible. The British soldiers, stretched along a 14-mile (23km) front, went ‘over the top’ under fine weather at 7.30 a.m., many of them advancing at a walking pace in expectation of limited resistance. (Moving at a steady uniform pace also allowed units and individuals to maintain effective communication links, rather than become strung out over the battlefield.) Instead, they walked into blistering hails of machine-gun fire and German artillery. Entire battalions of young men were hewn to pieces in minutes, their bodies lying out in blasted fields and amongst contorted wraps of barbed wire. Almost no significant territorial gains were made that day, and in many cases the units ended up back at their start lines, their ranks thinned down considerably compared to when they set out a few hours previously.

FIRST WORLD WAR CASUALTIES (DEAD, WOUNDED AND MISSING)

FRONTLINE VOICES:

BATTLE OF THE SOMME

War reporter Philip Gibbs wrote about what he saw on the first day of the Somme, 1 July 1916:

Before dawn there was a great silence. We spoke to each other in whispers, if we spoke. Then suddenly our guns opened out in a barrage of fire of colossal intensity. Never before, and I think never since, even in the Second World War, had so many guns been massed behind any battle front. It was a rolling thunder of shell fire, and the earth vomited flame, and the sky was alight with bursting shells. It seemed as though nothing could live, not an ant, under that stupendous artillery storm. But Germans in their deep dugouts lived, and when our waves of men went over they were met by deadly machine-gun and mortar fire.

Our men got nowhere on the first day. They had been mown down like grass by German machine-gunners who, after our barrage had lifted, rushed out to meet our men in the open. Many of the best battalions were almost annihilated, and our casualties were terrible.

A German doctor taken prisoner near La Boiselle stayed behind to look after our wounded in a dugout instead of going down to safety. I met him coming back across the battlefield next morning. One of our men was carrying his bag and I had a talk with him. He was a tall, heavy man with a black beard, and he spoke good English. ‘This war!’ he said. ‘We go on killing each other to no purpose. It is a war against religion and against civilisation and I see no end to it.’

The poignancy of this single day was heightened by a feature of British Army recruiting practice in the early years of the First World War. At the start of the conflict in 1914, the total manpower available to the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was just 250,000 regular troops. This was nowhere near enough to face the German onslaught in Western Europe, thus Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, on 6 August began an impassioned appeal for men to join the ranks of the military as volunteers. Hundreds of thousands of men signed up in a matter of days, causing chaos at recruiting stations and recruit training depots. The men were encouraged to join up not only by the patriotism that fuelled the early weeks of the conflict, but also in many cases by the simple desire to enlist with their friends and colleagues, often with the added bonus of escaping a grinding industrial existence in Britain. An extremely localised form of recruiting produced what were known as the ‘Pals Battalions’, units of men connected through living on the same street, working in the same company, or belonging to the same guild or society. Aside from their official battalion designations, these battalions had evocative titles such as the ‘Hull Commercials’, ‘The Grimsby Chums’, ‘Glasgow Tramways Battalion’ and ‘Footballers Battalion’. Some 300 Pals Battalions were formed in 1914–15.

Looking back, the romanticism and comradeship of the Pals Battalions masked an obvious truth – if a battalion was decimated in battle, the losses would have a disproportionate effect on the home community from which the battalion was formed. Such was proved in graphic fashion at the Battle of the Somme. In the space of that single, terrible opening day, entire battalions were virtually destroyed. The Leeds Battalion lost some 700 of its 900 men, and the famous Accrington Pals – more fully known as 11th (Service) Battalion (Accrington) East Lancashire Regiment – suffered 584 dead, wounded and missing of the 750 men who had joined the attack.

The Battle of the Somme would rumble on for months to come, wavering in its intensity and the levels of human destruction. By the time it ran out of steam in November 1916, for advances of no more than 5 miles (8km), the British and French troops had taken 623,000 casualties. The Germans had also lost half a million men on the Somme – this was no one-sided battle.

As appalling as the Somme was, it sits comfortably alongside other epic battles of the war, some with even more excessive casualty lists. Also in 1916, the vast clash of arms between the Germans and French at Verdun in north-eastern France resulted in nearly one million dead and wounded between 21 February and 20 December. The battle was actually little more than a colossal exercise in attrition, the outcome of German efforts to ‘bleed to death’ the French Army. The British battle known as Third Ypres – more popularly called the Battle of Passchendaele after one of its key landmarks – inflicted 310,000 casualties on the BEF, and 250,000 on the German forces. Not only was this battle a horrifying trial by fire for the men involved, but the landscape itself became an enemy. Heavy rainfall, plus the high water table in the clay-heavy soil of Flanders, meant that for much of the battle men fought through an endless, ripped landscape of vacuous mud, in which both men and horses could and did drown if they fell from their duckboard walkways. In 1918, the German Michael Offensive added another 1.5 million casualties between 21 March and 18 July.