The Black History of the White House (26 page)

Read The Black History of the White House Online

Authors: Clarence Lusane

Indeed, Roosevelt's firm belief in the superiority of the white race over all others likely fed his delusion that his paternalistic relationship with Booker T. Washington reflected a moral capacity that blacks did not and could not have. His softer form of racism may also have been driven by reciprocating political interests as well. While Roosevelt could claim that he provided black access to the White House (via Booker T. Washington), Washington received patronage positions (via Roosevelt) that he doled out to supporters as a power broker, accruing enough authority to create problems for his black rivals and enemies.

Thus, on the eve of the infamous White House family supper, neither Roosevelt nor Washington was prepared for the level of racist outrage that their dining together would unleash. While the event was certainly not a state dinnerâthe highest social occasion to which a guest may be formally invited to the White Houseâit may have been even more egregious to white supremacists, because it lacked the cover of political necessity or obligation. Dining with a black man was a personal choice of the president. In an indication of White House political obtuseness, the next day White House Secretary George Bruce Cortelyou issued a routine press release headlined “Booker T. Washington, of Tuskegee, Alabama, dined with the President last evening.”

20

The political and social reaction was immediate, thunderous, and explosive.

Southern newspapers and political leaders unequivocally condemned both President Roosevelt and Booker T. Washington for violating racial boundaries that had been established not only by previous presidents but by the entire edifice of white social propriety. While during the latter half of the nineteenth century the White House had opened its doors to black political leaders such as Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and others,

it was unheard-of that a black person of any standing would be granted the honor of a White House dinner (or any meal), perhaps the most powerful gesture of social equality that could be imagined. That grand gastronomical opportunity clearly had a “whites-only” label on it.

Southern memory was short. In 1798, during the administration of John Adams, Haitian President Toussaint Louverture had sent his representative, Joseph Bunel, to meet with the U.S. president to discuss a trade-related issue. One of the leaders of the 1791 Haitian revolution, Louverture wanted to win support from the United States as the new nation faced French and British threats. He offered to protect U.S. ships that came into the area on trading missions. Adams sought greater influence in the region and agreed to meet Louverture's representative. Bunel, who was mulatto, and his wife, who was black, had dinner with Adams, “the first-ever breaking of bread between an American president and a man [and woman] of color.” Southerners and even some Northerners were livid. The Bunels also dined with Adams's secretary of state, Timothy Pickering.

21

President Roosevelt had clearly misread the praise lavished on Booker T. Washington by whites to mean that he might be an exception to the prevailing social etiquette of white domination.

The viciousness of the attacks and calls for retribution against Roosevelt were unrelenting and offer a hideous portrait of the extent of white animus toward black people. Mississippi Senator James K. Vardaman said that after the dinner, the White House was “so saturated with the odor of the nigger that the rats have taken refuge in the stable.”

22

The

Memphis Scimitar

called the dinner “the most damnable outrage which has ever been perpetrated by any citizen of the United States.”

23

Former presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan wrote, “It is to be hoped that both of them will upon reflection realize the wisdom

of abandoning their purpose to wipe out race lines, if they entertain such a purpose.”

24

The reaction in the black community was a bit different. Perhaps most blacks, if they thought about it at all, viewed the occasion as a mild though irrelevant honor, especially given that the White House was doing nothing to address the rampant acts of terrorism being perpetrated against black communities. There were some who celebrated the eventâthough not necessarily Booker T. Washington himselfâsuch as activist and black emigration organizer Bishop Henry Turner, who stated paradoxically, “You are about to be the great representative and hero of the Negro race, not withstanding you have been very conservative. I thank you, thank you, thank you.”

25

Turner's overdrawn ebullience contrasted with the responses of other black leaders. The radical and longtime Booker T. opponent William Monroe Trotter rebuked the wizard of Tuskegee and called him a hypocrite for supporting social segregation between the races and then going to sup at the White House.

26

For Trotter and other black radicals, Booker T. Washington got his just deserts.

Washington himself appeared both perplexed and traumatized by the controversy. Only a few days after the White House dinner, he dined with Roosevelt once again, this time at Yale University after he and the president both received honorary degrees, an event that sparked no criticism. But he seemed not to understand that dining at the White House was a different issue altogether. Accustomed only to accolades and praise from whites, he was dumbfounded to find himself the target of racial hatred. His role as mediator of all things black was suddenly in jeopardy.

Back at the White House, the president and his staff went into urgent damage-control mode. The White House first sought to deny that the event had taken place at all, contradicting its

own press release that had reported the exact opposite. Further confusing matters, some White House staffers spread rumors that there had been a luncheon rather than a dinner, though it seems the difference would matter little to hard-core white supremacists. The press was also told that the Roosevelt women, the president's wife and daughters, absolutely had not been part of a dinner with a black manâfailing to mention that Washington had just sat next to Roosevelt's daughter Alice as they all dined together at the Yale supper.

Though Booker T. was not invited back to the White House, Roosevelt continued to work and consult with him, but more often behind closed doors or through intermediaries. And despite the public backlash from the supper scandal, Roosevelt would still call upon Washington to edit parts of his speeches that addressed racial concerns and later accepted an invitation to serve as a trustee at Washington's Tuskegee Institute.

27

Although the controversy eventually died down, its impact shaped White House politics for decades. No black person would be invited to dinner at the White House again for nearly thirty years. Ironically, that would occur during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt's distant relative, Franklin D. Roosevelt. The whites-only eating policy remained unbreached until 1929. Early that year, Herbert Hoover's wife, Lou, faced a dilemma involving the holding of her traditional tea at the White House for the wives of congressional members. She had to decide whether to invite Jessie Williams De Priest, the wife of Rep. Oscar De Priest, who had become the first African American elected to Congress in the twentieth century with his 1928 victory in Illinois. With the Booker T. WashingtonâTheodore Roosevelt dinner still echoing, to invite her to sit down with white Southern women would have undoubtedly infuriated white Southern leaders and voters. But not to invite her would insult not only

the De Priests but the black community as a whole, as well as many whites outside of the South. A tactically brilliant though racially cautious solution was found. Lou decided to have four sets of teas, the last of which, on June 19, 1929, would include Jessie De Priest and congressional wives whom she had consulted who did not object to having tea with an African American. She was still sharply criticized for that gesture, some Southern legislatures passing resolutions “condemning certain social policies of the administration in entertaining Negroes in the White House on a parity with white ladies.”

28

The Washington-Roosevelt incident signaled the full and complete lockout of millions of blacks from the nation's official political channels. If the president of the United States could be attacked for merely having supper with an accommodating black leader and then be seen to distance himself from that leader publicly, clearly other strategies were necessary to move issues of racial justice forward. Soon, thanks to Du Bois and other progressive blacks, the Niagara Movement would evolve into the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Some African Americans would embrace socialism, and the Garvey movement would emerge as well. The real legacy of the Booker T. Washington dinner has been that it catalyzed a new and more radical path for the black movement for freedom.

One final mockery redounded from the affair. On October 17, 1901, the day after the Washington dinner fiasco, Roosevelt issued an order officially naming the president's residence “the White House.”

29

Jim Crow in the White House (and Congress)

Any black man who votes for the present Republican Party out of gratitude . . . is born a fool. Equally no

Negro Democrat can for a moment forget that his party depends primarily on the lynching, mobbing, disfranchising South. Toward any Third Party advocates the intelligent Negro must be receptive. . . .

30

â W. E. B. Du Bois

The White House dinner controversy, however dramatic, should not have been unexpected. It occurred in the period following Reconstruction, when white Americans broadly and often forcefully suppressed the rights of Americans of color. The White House was not immune to the social, cultural, and political dictates of the period, and the growth of segregation went hand in hand with the political aspirations, agendas, and strategies of each of the White House occupants from Andrew Johnson to Dwight Eisenhower, with a few notable exceptions along the way. While a number of presidents expressed personal feelings of opposition to Jim Crow and the oppression of blacks, none used the power of the office to substantially confront Southern segregation and advance black rights. Indeed, many of the presidents during this period did all they could to perpetuate the racial power structure that kept whites at the top and everyone else on the bottom. For decades, the White House felt whiter than ever to most African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and other racially marginalized groups.

Racial politics at the White House, however, were more complicated than at the regional or state level. Unlike local and state seats of government, the White House had to project its leadership over the entire nation, which included not only a growing and organized black electorate but also progressives and radicals who were brown, red, white, and yellow and who were increasingly organizing for racial justice and equality. In

addition, as the United States's role in the global arena grew, particularly after World War I, foreign policy considerations had to be taken into account. Racial issues had manifested in the struggle to create the League of Nations and were critical to the objectives and themes of the United Nations. The Cold War would be particularly challenging to the segregationists and those who accommodated them, as the Soviets and newly independent African and Caribbean nations would point to the audacious racial hypocrisy of the South to undermine the U.S. claim to be the world's leading democracy.

The official naming of the president's home “the White House” in 1901 coincided with the domestic and global perception of the residence as a symbol of a racially constructed nation in deep conflict with both its founding call and frequent international exhortations for freedom and democracy.

The era began with the murder of Reconstruction. Critically ill and on its deathbed for years, it received its death blow with the Hayes-Tilden Compromise of 1876, which determined who would control the White House after that year's presidential election. As soon as Southern white leaders were able to return to power they began to institute “black codes” that segregated blacks and whites. These legalisms were enforced with coercive brutality inflicted on black communities by terrorist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, Red Shirts, White League, Southern Cross, Knights of the White Camellia, and other groups driven by notions of white supremacy and hatred for people of color. However Lincoln may have equivocated in addressing the needs of African Americans, his successors in the White House demonstrated scarcely any courage in challenging the multiple levels of institutional racism that had run rampant in the nation from the day it was founded. Following Andrew Johnson, who openly fought to advance mechanisms of white domination to preâCivil War levels, and down the line, the White House illustrated racial regression rather than racial progress.

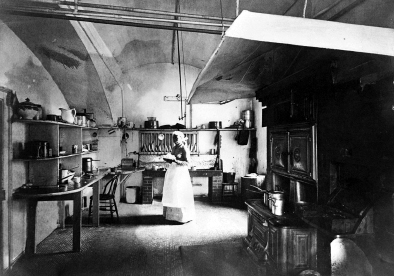

Black woman working in the White House kitchen, circa 1892

.

With African Americans freed from slavery but denied equality, black agitation and resistance grew in response to pervasive hostility, exclusion and abuse from white society. Black organizations such as the National Convention of Colored Men and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) built countrywide networks of activists who along with thousands of local groups organized and mobilized to overthrow systems of segregation. A central focus of the black community was the call for federal intervention to end lynching, a call that repeatedly fell on deaf ears. The movement for racial equality was also strengthened, for a time, by the presence of African Americans in the U.S. Congress. Nearly two dozen blacks served in Congress from the end of the Civil War to the turn of the twentieth century.