The Black History of the White House (30 page)

Read The Black History of the White House Online

Authors: Clarence Lusane

Jubilee Singers between 1870 and 1880

Blacks Entertainers at the Pre-1960s White House

Following Blind Tom, the White House also increased the variety of black entertainers it invited to perform there. From classical musicians to gospel singers, black performers appeared before the presidents and their guests and family. While some presidents preferred only white entertainers, many sought a variety of musicians and singers to perform before foreign dignitaries.

Gospel and spiritual groups were perennial favorites at the White House in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The first spiritual ensemble to be invited was the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who performed slave songs as well as spirituals. The name Jubilee was a reference to the year of jubilee as described in the twenty-fifth chapter of the Book of Leviticusâthe year in which all those enslaved are set free. The group started as a project to raise money for Fisk University, which was established in 1866 as a school open to students of all races. Many of the Jubilee Singers

had been formerly enslaved. The group toured both the United States and Europe and performed before kings and queens.

In 1872, the Jubilee Singers performed at the World Peace Festival in Boston and on March 5 of that year entertained President Grant at the White House. Despite the fame they had achieved, the group temporarily disbanded in 1878 due to exhaustion and a grueling travel schedule, but eventually reunited and continued to tour and perform. During the Bush administration, in 2008, the contemporary Fisk Jubilee Singers were selected as a recipient of the 2008 National Medal of Arts, the nation's highest honor for artists and patrons of the arts. The group continues to tour and perform today.

80

Although traditional black music was popular with presidents, it was not the only genre in which African Americans excelled.

As far back as 1878, African Americans were performing opera and classical music at the White House. While African American political leaders would find themselves more and more excluded as the century moved toward its conclusions, black entertainers would become a norm of sorts at White House functions. One leader would serve as a sort of bridge between the two. In addition to his ceaseless activism and journalism, not to mention holding a number of political offices, Frederick Douglass was also a dedicated violinist. But it was Douglass's grandson who became a professional violinist with a successful career that included performing at the White House. There is a rich and long history of virtuoso black violinists in the United States dating back to the central role that the instrument held during the slave era. At the same time, free blacks were also learning to play expertly, including Philadelphia's Francis Johnson (1792â1844) and Newark's Peter O'Fake (1820â1884).

81

Joseph Henry Douglass was born in 1869. Besides the training he received from his grandfather, he was educated at the Boston Conservatory. He traveled and toured in Europe and later taught at Howard University. When not busy writing, lecturing or traveling, Frederick Douglass gave lessons to his grandson, and the two often played Schubert together in the music room at Douglass's Cedar Hill home in southeast Washington. Frederick Douglass reportedly paid $1,000 for a violin while visiting Germany, and later gave the instrument as a gift to grandson Joseph Henry.

82

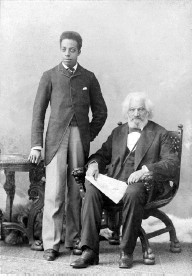

According to Kenneth B. Morris Jr., great-great-great-grandson of Frederick Douglass, Joseph Henry was the only grandchild ever photographed with his grandfather.

83

Frederick Douglass with his grandson, Joseph Henry Douglass, the violinist.

For a time, Joseph Henry Douglass worked as Chief of the Office of Inter-Agency Liaison of the National Institute of Mental Health, but left to pursue a life of music.

84

In September 1889, in the early days of his career, he played with the legendary James Reese Europe in Washington, D.C. James Reese Europe was the musician who would be credited with bringing early

forms of jazz to Europe during World War I. He was a lieutenant in the all-black 369th Infantry Regimentâbetter known as the “Harlem Hellfighter”âand director of the regiment's marching band. The September 26 concert was reportedly the first time a solo was played on the saxophone by an African American and African American woman, Elsie Hoffman.

85

For thirty years Douglass played across the globe and the United States, including, reportedly, every black education institution in the country.

86

He was often accompanied by his wife, Fannie Howard Douglass, who played piano. In 1914, he became one of the first violinists, black or otherwise, to record for the Victor Talking Machine Company, the leading phonograph producer at the time, but the recordings were never released.

87

He played for both President McKinley and President Taft.

88

Unfortunately, there is no detailed account of either concert. Despite having performed at the White House and in Europe, Joseph Henry Douglass, like virtually all black classical musicians, was forced to play in segregated venues for all of his public performing career in the United States.

89

African Americans in the opera world faced similar discrimination. Opera star Marie Selika Williams performed in the Green Room for President Hayes and his wife Lucy Webb Hayes on November 13, 1878, just two years after she first appeared in concert.

90

Her performance included Verdi's “Ernani, involami,” Thomas Moore's “The Last Rose of Summer,” Harrison Millard's “Ave Maria,” and Richard Mulder's “Staccato Polka,” according to researcher Deborah McNally.

91

First Lady Lucy Hayes was so impressed that she attended her concert fundraiser at St. Luke's Protestant Episcopal Church the next year in Washington, D.C.

92

A mark of the event's importance was the presence of Frederick Douglass, who introduced Williams. She also had a connection with the First Family, which,

like Williams, originally hailed from Ohio. She later toured Europe and performed before Queen Victoria. As with other black opera artists of the period, the racism of white society denied her the opportunity to perform in the formal opera world in the United States, thus her career remained limited.

Some black classical and opera stars, such as Sissieretta Jones, performed numerous times at the White House. Jones (born Matilda Jones), performed for Presidents Harrison, Cleveland, McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt.

93

Favorably compared to Italian opera diva Adelina Patti, she acquired the nickname “Black Patti,” which she disliked but used to her advantage. At her 1882 performance in the White House Blue Room before President Harrison, she sang “Swanee River” and the cavatina from Meyerbeer's

Robert le diable

. Like Marie Selika Williams, she also toured Europe, South America, the Caribbean, Australia, India, and parts of Africa, where there were more opportunities for a black American opera singer than at home. She built a review and a troupe called the “Black Patti Troubadours” that performed all over the United States. The Troubadours, unfortunately, made the most money performing “coon shows,” i.e., acting out white stereotypes of blacks, although she ended the show with selections from operas and spirituals.

94

No other black opera performers were invited to the White House until the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration decades later. Eleanor Roosevelt opened up the White House to a large number of black artists from different genres. Her most famous public act to support a black artist against discrimination occurred in 1939 when she helped arrange for opera star Marian Anderson to perform at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., after she had been turned down from performing at Constitution Hall, which was owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Marian Anderson, 1940.

The first lady was familiar with Anderson from her performance in the Monroe Room on the second floor of the White House in February 1936. The Daughters of the American Revolution had a whites-only policy, and they had rejected Anderson once before in 1935. They again refused to let her perform, and the Lincoln Memorial became the alternative site. Her performance was magnificent and an embarrassment for the Daughters of the American Revolutionâas was the First Lady's resignation from the organization.

Racist attacks on Anderson continued. Later that year, along with the North Carolina Spiritual Singers, Anderson gave a command performance at the White House before the king and queen of England. As historian Elise Kirk reports, a pro-segregationist Miami Democrat wrote in ire, “It is an insult to the British King and Queen who are caucasians [

sic

] to present a negro [

sic

] vocalist for their entertainment. Do you want to engender racial hatred which might lead to serious consequences

in the entire South?” The first lady's assistant, Edith Helm, replied with a somewhat racially stereotyped justification: “Mrs. Roosevelt asks me to acknowledge your telegram and to tell you that she is trying to give the King and Queen a picture of all American music. As the colored people are outstanding in a musical way, Mrs. Roosevelt feels that they should be presented with the others who will appear here.”

95

Anderson was not the first black opera singer to come to the Roosevelt White House. On February 9, 1934, the young soprano Lillian Evanti of Washington, D.C., performed for the Roosevelts at the White House. According to Kirk, she was the “first black to appear with an organized European opera company, the Nice Opera, in 1926.”

96

She was followed the next year by soprano Dorothy Maynor, who was described as having a “soaring bell-like voice,” and baritone Todd Duncan, who would sing at the White House on three more occasions after mesmerizing the president with his presentation of Cecil Cohen's “Death of an Old Seaman.”

Soprano Leontyne Price performed repeatedly at the White House during the Johnson, Reagan, and Carter administrations. On July 4, 1964, Price and composer Aaron Copland became the first artists to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which had been created in 1963 by President Kennedy to honor distinguished Americans in the fields of science, business, journalism, and theology as well as the arts.

97

Price's most politically significant performance was at the historic dinner that followed the signing of the peace accord between Egypt's Anwar Sadat and Israel's Menachem Begin. It had been agreed that each country, Egypt, Israel, and the United States, would choose an artist to perform at what was the largest White House dinner in history. Begin choose virtuoso violinists Itzhak Perlman and Pinchas Zukerman; Sadat picked an Egyptian trio (guitar, tabla,

and organ); and Carter selected Price. She sang the aria “Pace, pace, mio Dio” from Verdi's opera

La forza del destino

.

98

Another great opera artist to appear at the White House was Metropolitan Opera diva Grace Bumbry. Born in St. Louis in 1937, she rose to fame in the late 1950s and early 1960s with a series of sensational performances. When a segregated local conservatory refused to honor a scholarship she had won allowing her to attend classes, she decided to audition for Arthur Godfrey's popular “Talent Scouts” program, a performance that moved the host to tears and took place on the same day the Supreme Court announced the decision to ban segregated education.

99

At twenty-three, Grace Bumbry made her operatic debut at the Paris Opera Theater, one of the most prestigious and frightening stages to perform on, even for seasoned artists. The international press deemed it an unmitigated success. However, it was her role as Venus in a production of

Tannhäuser

that catapulted her to everlasting fame. Wieland Wagner, grandson of legendary composer Richard Wagner, organized the production and cast her as “the first black opera singer to appear at Bayreuth [Germany], the world's most revered shrine to the great composer and his art.”

100

While the opera was still in rehearsal, many critics and fans called the casting a cultural disgrace and worse. Bumbry's stellar performance, however, destroyed all criticism with the opening show; she received a thirty-minute standing ovation and forty-two curtain calls.