The Black History of the White House (24 page)

Read The Black History of the White House Online

Authors: Clarence Lusane

In addition to conferring with Douglass, President Lincoln also met with Sojourner Truth. Born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, in 1797, Isabella Baumfree became one of the nation's foremost advocates for both abolition and women's suffrage. Although an 1827 New York law freed her and all the state's enslaved black people, she had already escaped to another part of the state and was living independently with one of her children. A deeply religious individual, she adopted the name Sojourner Truth in 1843, believing it was sent to her through divine intervention. In an inspired and powerful talk delivered in 1851 at the Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio, known popularly as her “Ain't I a Woman” speech, she linked the struggles for black liberation and women's liberation, an ideological and political leap few took at the time. She stated:

Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that 'twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what's all this here talking about?

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a manâwhen I could get itâand bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?

81

By late 1864, Truth had become a great admirer of Lincoln, and that year she traveled from her home in Battle Creek, Michigan, to Washington, D.C. to gain an audience with him. She discovered that she would need someone to arrange the meeting and went to antislavery activist Lucy Colman, who turned to Elizabeth Keckly. Given her fortuitous position relative to the Lincolns, Keckly was able to set up the encounter, which took place in the early morning on October 29, 1864, at the White House. The meeting was thin in substance and more a courtesy call than a substantive discussion about the miserable condition and political future of the country's millions of black people. Nevertheless, Truth writes fondly of the occasion, stating “I must say, and I am proud to say, that I never was treated by any one with more kindness and cordiality than were shown to me by that great and good man, Abraham Lincoln, by the grace of God president of the United States for four years more.”

82

She noted that there were “colored persons” among those who were visiting Lincoln, including one black woman who needed help paying her rent.

83

In expressing their mutual admiration for each other she told him that although she had never heard of him prior to his becoming the nation's commander in chief, she considered him “the best president who has ever taken the seat,” and he “smilingly replied, âI had heard of you many times before that.' ”

84

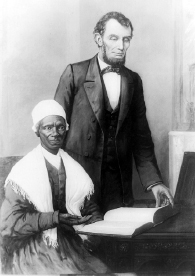

Sojourner Truth and Abraham Lincoln at the White House, October 29, 1864.

Toward the end of their discussion, he showed her a Bible that had been presented to him as a gift by a group of black people from Baltimore. That moment was captured in a very famous picture of Lincoln and Truth together.

As they ended their time together, Lincoln signed a book

that she had brought with her, writing, “For Aunty Sojourner Truth.” For researcher Bennett, Lincoln's calling Truth “Aunty” bolsters his assertion that Lincoln was not only policy-deaf when it came to black interests but harbored personal racist views as well.

85

For Bennett, it does not matter if Lincoln meant it as a term of endearment, which was likely the case. For her part, Truth never complained about the term.

Lincoln and Truth may have also met on other occasions. Lincoln made reference to other times that he had seen her, and it reportedly disturbed him when he discovered that on February 25, 1865, she had gone to the White House but had not been permitted to meet with him.

86

Like Keckly, Truth was interested in the welfare of black refugees from the war who were subsisting in the streets, alleys, and camps of Washington, D.C. On at least one of her trips to Washington, D.C., she sought to address the segregationist policies in the city even after slavery was abolished. She was also active in gathering food and clothing for black soldiers and civilians.

Although she never met with Lincoln personally, Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman also sought to influence the White House. Born into slavery in 1822, she escaped while in her twenties and led approximately twelve successful raids to free enslaved blacks. During the Civil War, she served the Union army as a spy, a nurse, and the commander of a military raidâthe first woman to take such a roleâin which she and her troops sailed up the Combahee River, destroyed Confederate outposts, and liberated more than 700 black people.

87

Tubman's views on what Lincoln should do to win the war are quoted in an 1862 letter written by white abolitionist Lydia Maria Child. The letter quotes Tubman, who refers to Lincoln as “Master,” saying:

Earliest known photo of Harriet Tubman, taken when she was already established as the Moses of her people.

88

I'm a poor Negro but this Negro can tell Master Lincoln how to save money and young men. He can do it by setting the Negroes free. Suppose there was an awful big snake down there on the floor. He bites you. Folks all scared, because you may die. You send for doctor to cut the bite; but the snake is rolled up there, and while the doctor is doing it, he bites you again. The doctor cuts out that bite; but while he's doing it, the snake springs up and bites you again, and so he keeps doing it, till you kill him. That's what Master Lincoln ought to know.

89

Reflecting the views of blacks, free and enslaved, Tubman implored Lincoln to kill slavery once and for all.

90

Famous, little-known, and unknown African Americans all trekked to the White House to lobby Lincoln during his

four-plus years in office. The issues on the table were substantial and often of national importance. Free blacks such as Keckly, and movement leaders such as Douglass and Truth, pioneered African American political access to the White House, and boundaries were redefined as new degrees of inclusion evolved. These encounters, developing in the context of profound national crisis, increased pressure on the reluctant president to see abolition as the only viable resolution. The cumulative impact of the chaos of war, massive escapes from slavery, agitation by abolitionists and free blacks, relentless pressure by Republican radicals, and, yes, the Emancipation Proclamation, all prepared the way for the formal end of slavery and a reconstruction of race relations in the United States. Lincoln walked an uneven, indirect, but successful path toward that end. He may have started his administration as an openly bigoted, colonization-promoting, politically averse, soft antislavery politician, but he evolved, reaching places that no U.S. president before him had dared go, and, it should not be forgotten, it cost him his life. Lincoln, in the end, evolved beyond the limits of his own political experiences and beyond the limits of the dominant political climate of his time.

Ultimately, abolition happened both in spite of and because of Abraham Lincoln. The cautious, hesitant, and vacillating Lincoln finally succumbed to the era-changing, slavery-despising, liberal policyâinitiating Lincoln. He challenged the doctrine of states' rights, the political safety valve for the South in insulating slavery from federal intrusion. He initiated political relations with African Americans that had not existed previously. His meetings to discuss (or preach) policy implied a notion of respect for the political intelligence and strategic thinking of (some) black Americans, a posture no previous president had come near. In the end, it was the grand crisis of the Civil War

that opened up the possibility of abolishing slavery once and for all, and Lincoln found himself in the position for it to occur on his watch.

Reconstruction, Rise and Fall

Lincoln did not live to see what some have argued was the most racially democratic epoch in U.S. history prior to the civil rights victories of the 1960s and 1970s: the period known as Reconstruction.

91

In that era, constitutional amendments, congressional legislation, and presidential orders sought to give vigor to the policies needed to help the millions of newly freed black men, women, and families integrate successfully into U.S. society. The Freedmen's Bureauâofficially titled the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Landâwas established by Congress in March 1865 as the main agency charged with addressing the educational, economic, medical, and other needs of Southern blacks. Offices were set up in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia in addition to the Washington, D.C. office.

92

While the Freedmen's Bureau did not distribute land confiscated from the Confederates to the newly freed, an earlier order did. On January 16, 1865, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman issued “Special Order 15,” which granted forty acres of arable land apiece to families on the coast of Georgia and the Sea Islands nearby. The families were also given some of the surplus mules that the army held.

93

Access to land would be a key element in the survival and independence of African Americans after the war.

The radical Republicans who held sway in Congress immediately after the war were also able to push through the Thirteenth Amendment (December 6, 1865), which ended slavery; the Fourteenth Amendment (July 9, 1868), which gave

the newly emancipated citizenship; and the Fifteenth Amendment (February 3, 1870), which granted voting rights to black men. Congress also passed civil rights acts in 1866 and 1875. The 1866 Civil Rights Act outlawed discrimination in housing, allowed for blacks to make and enforce contracts, legalized black ownership of property, and made it legal for blacks to give testimony in court. These policies and others were essential to initiate repair of the damage that centuries of white-perpetrated enslavement and human trafficking of blacks had wrought.

Actually, the program was carried out in two phases, known as Presidential Reconstruction (1865â1867) and Radical Reconstruction (1867â1877). In the first phase, the White House was seen as the principal driving force in developing, implementing, and enforcing policies that would benefit African Americans. While Lincoln may have demonstrated uncertainty and equivocation, his successor was clear where he stood: on the side of the Southern Confederates. In building what historian Doris Kearns Goodwin called his “team of rivals,” in 1864 Lincoln had chosen Tennessee Democrat Andrew Johnson as his vice president.

94

White House doors that were opened to blacks by Lincoln were slammed shut by Johnson. As Frederick Douglass observed, “Whatever Andrew Johnson may be, he certainly is no friend of our race.”

95

Johnson, a slaveholder prior to becoming president, acted immediately to restore and perpetuate white racial domination in the South. His personal views on race were hateful; he famously stated in Congress in 1844 that if blacks were given the right to vote it would “place every splayfooted, bandy-shanked, hump-backed, thick-lipped, flat-nosed, woolly-headed, ebon-colored Negro in the country upon an equality with the poor white man.”

96

The seventeenth president of the United States was openly racist, and his list of anti-black actions is long: Johnson failed

to intervene when black voters and activists came under attack from white terrorist groups; advocated and gave pardons to unrepentant Confederates; ousted black employees from the Freedmen's Bureau; rescinded Maj. Gen. Sherman's order to give land to blacks; vetoed (re)funding of the Freedmen's Bureau; and vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866.