The Beasts that Hide from Man (2 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

THE

DOBHAR-CHÚ, A

SUPPOSEDLY MYTHICAL BEAST from Ireland, is also called the

dobarcu

, master otter, and king otter, and was classed by English folklorist Dr. Katharine Briggs as a prototype animal representing all of its kind. In

The Anatomy of Puck

(1959), Briggs termed it the master otter, and it was evidently larger than normal otters because she stated that it was said to have appeared once at Dhu-Hill, with “about a hundred common-sized otters’

7

in attendance. According to legend, an inch of the master otter’s pelt will prevent a ship from being wrecked, a horse from injury, and a man from being wounded by gunshot or other means.

In

Myth, Legend and Romance: An Encyclopaedia of the Irish Folk Tradition

(1990), Dr. Dáithí ó hOgáin described it as a large male otter called the king otter, reiterating much of the information presented by Briggs but also noting that it was totally white in color except for its black ear tips and a black cross upon its back, and that it never slept. Yielding an unexpected parallel with the werewolf legend, this creature could only be killed with a silver bullet, and its killer would himself die no longer than 24 hours afterwards.

DOCUMENTS

Until quite recently, the above was all that I knew concerning the

dobhar-chú

—but in 1996, one of my correspondents, librarian Richard Muirhead, then of Wiltshire, southern England, kindly supplied me with several additional sources of information. These offer a much more detailed, and sinister, insight into Ireland’s most mystifying mammal.

Take, for example, the following letter, written by Miss L.A. Walkington and published by the journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland in 1896:

When on a recent visit to Bundoran [in County Leitrim, northwestern Ireland], we heard a legend concerning a tombstone in the graveyard of Caldwell [Conwall], which induced us to visit the place. The story is as follows: A young married woman went to wash her clothes in a stream near the house, and an animal called by the natives a dhuraghoo (that is spelled as pronounced, but I have never seen the word written), came out of the river and attacked her. Her husband (or brother according to some accounts) missing her went to look for her, and found her dead and the beast sucking her blood. The dhuraghoo attacked the horse; for the husband seems to have been on horseback. The horse being frightened, ran away, but became exhausted at a village called from this circumstance Garronard

{garrou

, a bad horse; ard, a high place). The dhuraghoo is said to have gone “through” the horse and to have killed it. It was then speared by the husband who at the same time killed its young one. The dhuraghoo is said by some to have been an animal half wolf-dog, half-fish, by others an enormous sea-otter…Two other tombstones are shown in connexion with the story, one bearing an image of the horse, and said to be that of the husband. Perhaps some antiquary may be able to throw light on the legend and on the nature of the dhuraghoo.

In a later issue of this journal for 1896, Miss Walkington’s letter drew the following response from H. Chichester Hart:

I have heard at Ballyshannon, a few miles from Bundoran, the following account of the “Dorraghow,” as it was pronounced in that district. He was “The King of all the Lakes, and Father of all the Otters. He can run his muzzle through the rocks. He was as big as five or six otters.” My informant thought he was long dead.

The master otter also appeared in the poem “The Old House,” within a 1950s anthology,

Further Poems

, by Leitrim poetess Katherine A. Fox. The relevant lines read:

The story told of the

dobhar-chu

That out from Glenade lake

Had come one morning years ago

A woman’s life to take.

During his research, Richard Muirhead also uncovered a much longer poem, of unknown source, titled “The Dobhar-chú of Glenade” (whose first verse opened this chapter), which is devoted entirely to the master otter’s deadly attack upon the hapless maiden and its fatal encounter with her vengeful husband. Regrettably, its style is somewhat lurid and turgid, as witnessed by the following excerpt:

She having gone to bathe it seems within its waters clear

And not returning when she might her husband fraught with fear

Hastening to where he her might find when oh, to his surprise.

Her mangled form still bleeding warm lay stretched before his eyes.

Upon her bosom snow white once but now besmeared with gore

The Dobarcu reposing was his surfeitting been o’er.

Her blood and entrails all around tinged with a reddish hue.

“Oh God,” he cried, “tis hard to bear but what am I to do”.

Shakespeare it ain’t, that’s for sure! Nevertheless, its 16 verses yield the most detailed version of this story currently known to me, and it is therefore of great value.

It dates the incident as occurring 200 years ago (which, for reasons revealed later, suggests that the poem itself may date from around 1920), and features a man called McGloughlan who lived close to the shore of Glenade Lake, County Leitrim, with his wife, Grace Connolly.

DOBHAR-CHÚ

OF GLENADE LAKE

One bright September morning, Grace visited the lake to bathe, but when she did not return home her husband retraced her steps, and upon reaching Glenade he found her dead body, torn and bloodstained—with her murderous assailant, the

dobhar-chu

, lying across her bosom. Maddened with grief and rage, he raced home for his gun, returned to the scene of the horrific crime, and shot his wife’s killer dead. In the fleeting moments before it died, however, the

dobhar-chu

gave voice to a single piercing squeal—which was answered from the depths of the lake. Seconds later, the dead creature’s avenging mate surfaced, and the terrified McGloughlan fled.

Reaching home, he told his neighbors what had happened, and they advised him to flee the area at once. This he did, accompanied by his loyal brother, both riding speedily on horseback, but doggedly pursued by the whistling

dobhar-chu

. After 20 miles, they reached Castlegarden Hill, dismounted, and placed their horses lengthwise across the path leading into it. Standing nearby, with daggers raised, they awaited the arrival of their shrill-voiced foe—and as it attempted to dash through the horses’ limbs, McGloughlan plunged his dagger downwards, burying it up to its hilt within the creature’s heart.

DOBHAR-CHU

MONUMENTS

Needless to say, it would be easy to dismiss the story of Grace Connolly as nothing more than an interesting item of local folklore—were it not for the existence of two

dobhar-chu

tombstones commemorating the above episode. These are documented in an article by Patrick Tohall, published by the journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland in 1948. The first of the two monuments is a gravestone in Congbháil (Conwall) Cemetery in the town of Drumáin (Drummans), forming part of the approach to the Valley of Glenade from the coastal plain of north County Leitrim and south County Donegal, and just a few miles south of Kinlough, beside the main road leading from Bundoran to Manorhamilton.

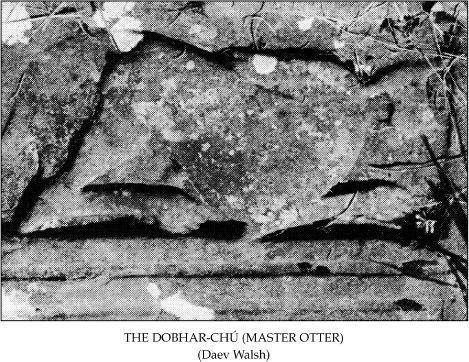

A recumbent flag of sandstone roughly four feet, six inches by one foot, ten inches and dated September 24,1722, what makes this the more interesting of the two stones is that it actually portrays the

dobhar-chu

itself, described by Tohall as follows:

The carved figure is set in a panel about

17 Vi

ins. by 7 ins. It shows a recumbent animal having body and legs like those of a dog with the characteristic depth of rib and strength of thigh. The tail, long and curved, shows a definite tuft. The rear of the haunch, and still more the tail, are in exceptionally low relief, apparently due to the loss of a thin flake from the face of the slab. So far the description is canine. The paws, however, appear unusually large, while the long, heavy neck and the short head into which it shades off, together with the tiny ears are all like those of an Otter or such Mustelida.The head and neck are bent backward to lie flat on the animal’s backbone. A human right hand, clenched and with fingers facing the spectator, is shown holding a weapon which has entered the base of the neck and reappears below the body in a short stem which suddenly enlarges to finish as a barb.

The article contains a photo of this depiction taken by society member Dr. J.J. Clarke. Unfortunately, in my files’ photocopy of Tohall’s article, the illustrations had not reproduced well. In autumn 1997, however, after I had communicated with

Fortean Times

correspondent Daev Walsh concerning it, he and a colleague, Joe Harte, independently visited the

dobhar-chú

gravestone in autumn 1997. Not only were they both able to confirm that it still existed, they also took some excellent photographs of it, which they kindly passed on to me. These lucidly portray the carved

dobhar-chu

, revealing that its head is indeed small and somewhat lutr ine. Equally, after studying the photos, I agree with Tohall’s description of its body as canine—almost greyhound-like, in fact, except for its large paws and lengthy neck.

Interestingly, when I showed these pictures to various cryptozoological colleagues, some of them mistakenly assumed that the clenched hand of the

dobhar-chu s

slayer was actually the creature’s head! However, it is far too small to be this, and when the photos are viewed closely, the fingers of the clenched hand, which face the camera, can be clearly discerned gripping a spear-like weapon, as can the creature’s real head, thrown backwards across its back. Even the thin line of its mouth is readily visible.

Some of the wording on the gravestone is still legible too, identifying the person buried beneath as Grace Con, wife of Ter MacLoghlin. According to Tohall, she was still spoken of locally, but as Grainne, not Grace, and he also pointed out that Ter is undoubtedly short for Terence, and that it is Gaelic custom for a married woman to retain her maiden name, which explains why Grace was referred to on her gravestone as Con rather than MacLoghlin. Tohall considered it likely that her gravestone was prepared while her death was still fresh in local memory, because similar gravestones in this same cemetery are characteristic of the period 1722 to 1760. This, then, would appear to be the last resting place of the hapless young woman killed by the

dobhar-chu

, whose own existence is commemorated here too—all of which seemingly elevates the episode from folklore into fact.

As recently as World War I, the second

dobhar-chu

tombstone, believed to be that of Grace’s husband, Ter, was still in the cemetery of Cill Rúisc (Kilroosk), at the southern entrance to Glenade, but had broken into two halves. At some later date, these were apparently placed up onto a boundary wall, and subsequently disappeared. Fortunately, however, at the time of Tohall’s research it was still well remembered by all of the region’s older men, who stated that it depicted some type of animal, and was popularly known as the Dobhar-Chú Stone. When asked whether the animal had resembled a dog, the only person who could recall the creature’s appearance stated that it was more like a horse.

Recalling the story of the

dobhar-chu

in his article, Tohall placed the home of Grace (or Grainne) and her husband in the townland of Creevelea at the northwest corner of Glenade Lake, and (like L. A. Walkington, above) stated that Grace visited the lake to wash some clothes (not to bathe, as given in the 16-verse poem). Indeed, several variations of the story exist elsewhere in the general vicinity of Glenade, but Tohall believed that the Conwall tombstone was particularly important—for constituting possibly the only tangible evidence for the reality of the

dobhar-chu

, which, incidentally, appears in ancient Scottish lore too.

The Isle of Skye, for example, in Scotland’s Inner Hebrides, is said to harbor a larger-than-normal type of otter dubbed “the king of the otters,” with a white spot on its breast. It is only rarely spied and is very difficult to kill, but the pelage from one of these beasts is claimed to guarantee victory in battle to anyone who possesses it.

Tohall also offered some interesting reflections upon the terminology of the master otter’s native name. Both in Ireland and in Scotland,

“ dobhar-chú,”

which translates as “water-hound,” has two quite different meanings. One is merely an alternative name for the common otter

Luira luira

, but is rarely used in this capacity nowadays (superseded by

“mada-uisge”)

. The other is the name of a mythical otter-like beast, and is still widely used in this capacity within the County Leitrim region. Tohall reserved the most intriguing insight into the master otter concept, however, for the closing sentence of his article: