The Beasts that Hide from Man (3 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

The best summary of the idea is set out in the records of the Coimisium le Béaloideas by Sean ó h-Eochaidh, of Teidhlinn, Co. Donegal, in a phrase which he heard in the Gaeltacht: “the Dobharchú is the seventh cub of the common otter”

(mada-uisge):

the Dobhar-chú was thus a super otter.

Another unusual creature, and name, apparently relating to the

dobhar-chu

is the so-called “Irish crocodile.” A terrifyingly close encounter with one of these mystery beasts allegedly occurred at the six-mile-long Lough Mask (Measg), in County Mayo, western Ireland, in or around 1674, and was documented by Roderick O’Flaherty in his book

A Chorographical Description of Wesi or H-Iar Connaughi

(1684) as follows:

Here is one rarity more, which we may terme the Irish crocodil [sic], whereof one as yet living, about ten years ago [1674], had sad experience. The man was passing the shore just by the waterside, and spyed [sic] far off the head of a beast swimming, which he tooke to have been an otter, and tooke no more notice of it; but the beast it seems there lifted up his head, to discern whereabouts the man was; then diving, sworn [sic] under water till he struck ground; whereupon he runned out of the water suddenly, and tooke the man by the elbow, whereby the man stooped down, and the beast fastened his teeth in his pate, and dragged him into the water; where the man tooke hold on a stone by chance in his way, and calling to minde he had a knife in his pocket, tooke it out and gave a thrust of it to the beast, which thereupon got away from him into the lake. The water about him was all bloody, whether from the beast’s bloud [blood], or his own, or from both, he knows not. It was of the pitch of an ordinary greyhound, of a black slimy skin, without hair, as he immagined [sic]. Old men acquainted with the lake do tell there is such a beast in it, and that a stout fellow with a wolf dog [Irish wolfhound?] along with him met the like there once; which after a long strugling [sic] went away in spite of the man and dog, and was a long time after found rotten in a rocky cave of the lake, as the water decreased. The like, they say, is seen in other lakes of Ireland; they call it

Dovarchu

, i.e. a water-dog, or

Anchu

, which is the same.

As can be seen from this description, Lough Mask’s “Irish crocodile” certainly compares very closely with the Glenade

dobharchu

—especially if one assumes that the former beast was not actually hairless, but instead possessed short hair, which, when wet, adhered so closely to its body that it seemed to its human victim to be shiny and hairless (as is also true with normal otters). Peter Costello documented this report in his own book,

In Search of Lake Monsters

(1974), and he too believes that the

dobhar-chu

and Irish crocodile are one and the same creature.

DOBHAR-CHU?

Today, the world beyond Glenade seems to have forgotten all about the

dobhar-chú

and its sinister deeds, but I wonder whether it may be premature for cryptozoology to assume that this mysterious animal is entirely confined to the shadows of the distant past—for it may conceivably have made some unexpected appearances as recently as 1968.

County Sligo (origin of a story featuring a horned specimen of

dobhar-chu)

is sandwiched between County Leitrim to the right, and County Mayo to the left. Several islands are present off the western coast of Mayo, including Achill, whose principal cryptozoological claim to fame is Sraheens Lough, a small lake said to be frequented by strange water monsters. Most of Ireland’s examples are of the “horseeel” variety—sinuous entities with horse-like heads, which may conceivably be undiscovered modern-day representatives of those supposedly long-extinct serpentine whales known as zeuglodonts.

The Sraheens Lough monster, however, is very different. On the evening of May 1, 1968, two local men, John Cooney and Michael McNulty, were driving past this lake on their way home when suddenly an extraordinary creature, shiny dark-brown in color and clearly illuminated by their vehicle’s headlamps, raced across the road just in front of them and vanished into some dense foliage nearby. They estimated its height at around two and a half feet and its total length at eight to ten feet, which included a lengthy neck, and a long sturdy tail. It also had a head that they variously likened to a sheep’s or a greyhound’s, and four well-developed legs, upon which it rocked from side to side as it ran. Just a week later, a similar beast crawled out of the lake as 15-year-old Gay Dever was cycling by. It seemed to him to be much bigger than a horse, and black in color, with a sheep-like head, long neck, tail, and four legs (of which the hind pair were the larger). Other sightings were also reported during this period, but the identity of the animals) was never ascertained.

In the 13-volume encyclopedia

The Unexplained

, edited by Peter Brookesmith, and first published in part-work form during the early 1980s, an artist’s reconstruction of the Sraheens Lough monster appeared in an article on Irish lake monsters written by Janet and Colin Bord (reproduced in a later compilation,

Creatures From Elsewhere

, in 1984). The illustration was based upon the eyewitness accounts given above for this monster, but it also happens to be exceedingly similar to the Conwall gravestone’s depiction of the

dobhar-chu

. Both share a sleek body and powerful hindquarters, long slender tail, lengthy but not overly elongated neck, distinct paws, and relatively small head. Indeed, one could easily be forgiven for assuming that the two illustrations had been based upon the same animal specimen (let alone species). Could such an arresting degree of morphological similarity be nothing more than a coincidence, or is the

dobhar-chu

still in existence amid the countless lakes of the Emerald Isle?

Cryptozoological skeptics have pointed out that with a circumference of only 1,200 feet, surely Sraheens Lough is too small to support water monsters. However, anything capable of running across roads on four sturdy limbs is equally capable of moving from one lake to another, not residing permanently in any one body of water—which could explain why sightings of monsters in Sraheens Lough are sporadic rather than regular.

Judging from the data presented in this coverage, if the

dobharchu

is a real animal it is clearly much more distinctive than just an extra-large version of the normal otter — and the sea otter

Enhydra lutris

is an exclusively marine species that never reaches British coasts — but until a specimen is obtained (if ever), it will continue to linger with leprechaun-like evanescence amid the twilight limbo between Celtic folklore and contemporary fact.

A…case worthy of note is that of Isadora Versano, the well-known journalist and duellist, who was found stark staring mad with a matchbox in front of him which contained a remarkable worm, said to be unknown to science

.S

IR

A

RTHUR

C

ONAN

D

OYLE

—“T

HE

P

ROBLEM OF

T

HOR

B

RIDGE,” IN

T

HE

C

ASE

-B

OOK OF

S

HERLOCK

H

OLMES

WHILE REMAINING FORTUNATE ENOUGH NEVER TO have encountered an unidentified beast as deadly as the make-believe monster cited above, during my many years of cryptozoological research and documentation I have publicized a number of mystery creatures that were hitherto largely or wholly unknown even to the cryptozoological community

To my mind, however, by far the most extraordinary member of this eclectic collection of cryptozoological newcomers is indeed a monstrous worm—a certain venomous vermiform with a truly electrifying presence…in every sense of the word!

Those nomadic tribesmen who share its sandy domain in the southern expanse of Mongolia’s vast Gobi Desert refer to it as the

allghoi khorkhoi

(also variously transliterated into English as

allergorhai horhai

and

olgoj chorchoj)

. Conversely, those few Westerners who have heard tell of it have very appropriately dubbed it the Mongolian death worm.

According to the nomads’ testimony, this astonishing animal can not only squirt a lethal corrosive venom, but also kill people merely by touching them (directly or indirectly), in a mysterious yet instantaneously fatal manner highly suggestive of electrocution!

This present chapter is an abridged version of my article “Meet Mongolia’s Death Worm—The Shock of the New,” published in

Fortean Studies

in 1998, which is the most detailed account ever published in relation to one of cryptozoology’s latest, and greatest, enigmas.

DEATH WORM DATA AND

DOCUMENTATION

ALLGHOIKHORKHOI

I first learned of the Mongolian death worm in 1995, when, while perusing a

World Explorer

issue from 1994,1 came upon an article titled “In Search of the Killer Worm of Mongolia,” authored by Ivan Mackerle. It described the first of two Gobi expeditions led by him during the 1990s in quest of the

allghoi khorkhoi

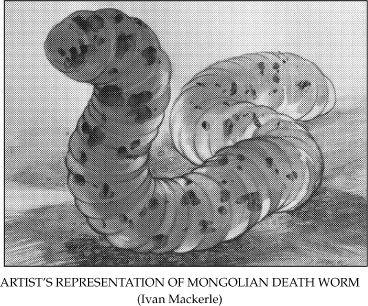

—a creature that seemed so utterly fantastic that at first I wondered whether the entire article was a hoax, especially as there were no accompanying biographical details regarding its author, or even any expedition photos.

In June 1996, however, a more detailed account by Ivan Mackerle was published in

Fate

, along with background information concerning him, as well as photographs depicting his search. The biographical data revealed that he was an author from Prague who has investigated a number of mysteries and regularly appeared on Czech television and radio. And when I pursued further lines of enquiry, I discovered that he was also a qualified design engineer and a well-respected explorer. In short, Ivan Mackerle was evidently a responsible researcher whose publications could be taken seriously.

Accordingly, I began communicating with Ivan by telephone and letter concerning the death worm and other cryptids. During our continuing correspondence, Ivan has very kindly made available to me for use in my own writings a veritable archive of material, most of which had never previously been cited in any English-language publication, and which comprises a considerable proportion of the data presented here. He also generously provided all the English translations of the various excerpts from Czech, Russian, and Mongolian sources quoted here or in my original

Fortean Studies

article.

Somewhat unappetizingly, the death worm earns its native name from its alleged resemblance to an animate cow’s intestine—

“allghoi khorkhoi”

translates as “intestine worm.” A succinct account of this grotesque creature is provided in a detailed information sheet compiled by Ivan in July 1997, which assimilates data gathered during his expeditions and extensive bibliographical research. In the English translation of his information sheet, the death worm’s “biography” reads as follows:

Sausage-like worm over half a metre [18 inches] long, and thick as a man’s arm, resembling the intestine of cattle. Its tail is short, as [if] it was cut off, but not tapered. It is difficult to tell its head from its tail because it has no visible eyes, nostrils, or mouth. Its colour is dark red, like blood or salami…It moves in odd ways—either it rolls around or it squirms sideways, sweeping its way about. It lives in desolate sand dunes and in the hot valleys of the Gobi desert with saxaul plants underground. It is possible to see it only during the hottest months of the year, June and July; later it burrows into the sand and sleeps. It gets out on [top of] the ground [i.e. sand] mainly after the rain, when the ground is wet. It is dangerous, because it can kill people and animals instantly at a range of several metres.

Area of its appearance: Galbin Gobi, Dzagsuudzh Gobi, Ondoer Gobi, Jungaria Gobi, Khaldzan Uul, Orag Nuur, Khoerkh, Khoet. It is in the south part of Mongolia near the Chinese border.