The Battle of White Sulphur Springs (17 page)

Read The Battle of White Sulphur Springs Online

Authors: Eric J. Wittenberg

Dr. John A. Hunter, the Confederate medical director, designated the world-famous White Hotel, Greenbrier Resort, as a field infirmary for those wounded in the Battle of White Sulphur Springs. While the battle raged on August 26, George Patton's wife, Sue, and their three children were a scant three miles away, occupying a cabin at the Greenbrier. Sue Patton heard the guns barking all day, and when battle casualties were brought to the Greenbrier for medical care, she rolled up her sleeves and helped to tend to the wounded. Patton's seven-year-old son George William joined in, “following my mother around with a bucket and sponge. The smell was so awful that my mother fainted and had to be carried out.” Colonel Patton himself didn't get over to the Greenbrier to see his family until August 28, and when he did make his way there, he was so dirty and bedraggled that George William did not recognize him right away.

340

Brigadier General Gabriel Wharton, who commanded another of Jones's infantry brigades. Blue & Gray

magazine

.

Major General Sam Jones was worried and had been for several days. He did not believe that Patton's single brigade would be able to stop Averell's raid if the New Yorker received reinforcements from Scammon's command. Jones called out the Home Guardâmostly composed of men over the conscription age of forty-fiveâto protect the New River Bridge and the Virginia Central Railroad.

341

Although he had asked Confederate secretary of war James Seddon to send him the brigades of Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins and Brigadier General Gabriel Wharton, which had been detached from Jones's department and sent to the Army of Northern Virginia, on August 24, he repeated that request. Although Jones ordered the two brigades to return by way of Staunton and Warm Springs, they did not arrive in time to make a difference, which only added to Jones's rising level of concern that his available forces would not be able to prevent Averell from breaking through Patton's roadblock.

342

Colonel William L. “Mudwall” Jackson had ordered Major Joseph K. Kesler to take a detachment of the 19

th

Virginia Cavalry to Covington and, if possible, to Lewisburg to ascertain and report the movements of Averell's force. The 20

th

Virginia Cavalry, another portion of Jackson's command, under command of Colonel William W. Arnett, arrived at Warm Springs and reported that Averell had moved on from Warm Springs and that the enemy's infantry had fallen back to the Gatewood Plantation in Pocahontas County. Jackson ordered Arnett to scout after the enemy in the hope of learning more that would enable them to interdict Averell's command and gain some revenge for the humiliation they had received at Huntersville a few days earlier.

343

Patton and his weary Southern infantrymen hunkered down behind their barricade and waited to see whether Averell would renew the attack in the morning.

6

Averell Withdraws

Averell hoped that by waiting, either he would receive reinforcements and a fresh supply of ammunition or Patton would retreat. With the coming of dawn, Averell discovered not only that Patton's stubborn infantrymen were still there but also that they had received reinforcements in the form of Corns's five companies of cavalrymen. He heard no word from Scammon and realized that he had no choice but to withdraw. Averell made detailed arrangements to make a prompt withdrawal from the battlefield in the face of the enemy. “The ambulances loaded with wounded, the caissons, wagons and long columns of horses were placed in proper order upon the road, details made for the attendance of the wounded, trees prepared to fell across the gorge when our artillery should have passed, and commanding officers received their instructions,” Averell wrote in his after-action report.

344

William Woods Averell was a very intelligent man, and he had learned from his prior experiences. On March 17, 1863, his Second Cavalry Division of the Army of the Potomac's Cavalry Corps had fought the Battle of Kelly's Ford. The Confederate defenders delayed the Union advance for nearly three hours by felling trees across the road, forcing Averell to bring up axmen to clear the abatis created by the felled trees. The delay bought sufficient time for the cavalry brigade of Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee and a battery of Confederate horse artillery to reach the battlefield at Kelly's Ford. The delay engendered by the felling of those trees cost Averell the initiative in the battle and greatly frustrated his efforts to reach Culpeper.

345

The painful lesson taught by that frustrating experience still stung the New Yorker, and he decided to use the same tactic on Patton's infantrymen and his small force of cavalry. He hoped it would be as successful as the Confederate use of that tactic had been at Kelly's Ford five months earlier.

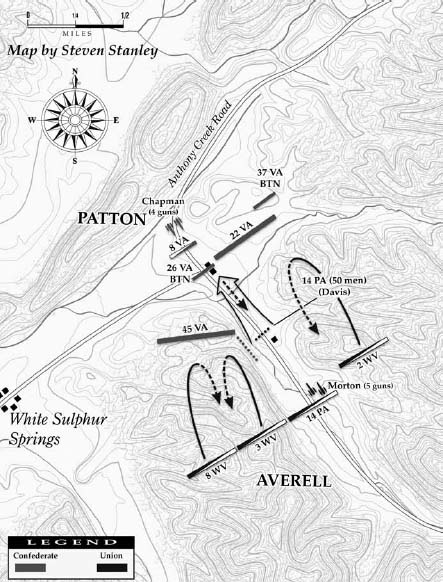

Day two of the battle, August 27, 1863.

Averell had his pioneers partially chop down the largest trees during the night so that they were ready to fall across the gorge and block the pursuit of the enemy with just a few more whacks of an axe. The plan worked to perfection. “As soon as we had passed the gorge, the trees went crashing down completely obstructing it,” recorded an officer of the 2

nd

West Virginia.

346

Early on the morning of August 27, Major General Sam Jones, Patton's commander, reported to the Confederate War Department. “Some desultory firing this morning early, and expect the fight to be renewed any minute.”

347

He was rightâAverell intended to make a final attempt to break through Patton's line. “At daybreak the attempt was again made to storm our position,” reported Patton, “but with so little spirit that it was evident that the enemy had lost confidence.”

Averell's troopers advanced at about five o'clock that morning and drove in Lieutenant Colonel Edgar's pickets. A “desultory fire was kept up between our sharpshooters and those of the enemy until about 11 a.m.,” reported Edgar, “at which time a spirited fire was commenced, which was continued until the enemy retired.”

348

Averell called for fifty volunteers to make a mounted charge on the barricade. Corporal William A.R. Davis of Company G of the 14

th

Pennsylvania answered the call. “We had to charge by fours,” he recalled, “so when we got there, not a man was left on horseback but Sgt. McCay, who wheeled his horse and got back.” Averell ordered these men to dismount and use their carbines if they could not break through the barricade. “I was left there with only one man,” recalled Davis, “and he could not fire his carbine for he was wounded and dying, with his back against the barricade.” Davis left him there and headed off alone on foot until he spotted the rest of the brigade's dismounted men, all of whom had had their horses shot out from under them all along the road on the way to the barricade. “There must have been some unseen hand that protected me through that storm of lead,” recalled a relieved Davis. He jumped in between two logs that lay on the side of the road, landing among other troopers of his regiment. They remained there, exposed to fire from both sides, for nearly two hours before making a mad dash to safety. “If I had stayed at the barricade I would be dead and buried away down in Dixie now,” concluded Davis.

349

Colonel William H. Browne's 45

th

Virginia faced only one attack on the morning of August 27, so Browne deployed a line of skirmishers from his left wing along the ridge line, enabling his men to maintain a cross-fire to the position held by Edgar's Battalion, meaning that the Confederates laid down a deadly fire that discouraged further attacks by Averell's horse soldiers.

350

Chapman's guns opened again, and Morton's guns replied, and the prior day's vicious counter-battery resumed.

351

The deadly fire by the 45

th

Virginia shoved the blue-clad troopers back a short distance. “I tell you I done some running and hollowing after them until I came to a house in a bottom that the enemy had sheltered in,” recalled a private of the 45

th

Virginia.

The ground around the house lie so thick with dead and clothes burnt off of them there was barley room to place our feet, it was so sad I quit yelling. Next we passed a house on side of road with amputated limbs thrown out at the window as large as hay stacks. Next we came to dismounted cannons in a little bottom and artillery horses with their rumps shot off which showed the destructive work of our cannons.

352

Patton also reported that the blue-clad horse soldiers maintained a brisk small-arms fire until late morning, when his troops repulsed another “ineffectual” attack.

353

Major R.A. Bailey, now in command of the 22

nd

Virginia Infantry, left an especially colorful description of the action on the morning of August 27: “At daybreak of the 27

th

, the enemy opened on us again and kept up a spirited fire until about 11 a.m., when they again attempted to form and charge us; but were whipped, scattered, and driven in disorder back before they could form.”

354

After Patton repulsed that final attack, Lieutenant Colonel John J. Polsley of the 8

th

West Virginia reported that the enemy was moving to flank Averell's rear.

355

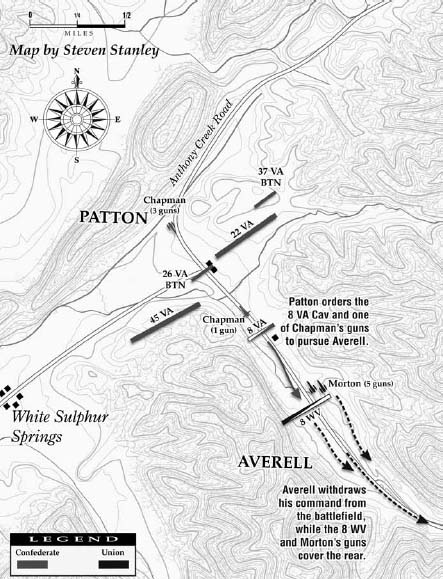

With this unwelcome news, Averell realized that his men were desperately low on ammunition and that Scammon's troops were not going to make it to the battlefield in time to tip the balance.

356

Left with no alternative, Averell ordered the withdrawal of his command at about 10:30 a.m.

357

The blue-clad horse soldiers bore off all of their wounded who could be transported and left the rest behind in the care of assistant surgeon C.M. Worthington of the 14

th

Pennsylvania Cavalry.

358

It would be a fighting withdrawal. Averell had his cannons double-shotted with the last rounds of canister, ready to tear gaping holes in the ranks of any Confederates who might try to pursue.

359

By 11:15 a.m., his column was moving off in good order, with his rear guard manning the barricades in an effort to buy time for the main body to reach safety.

360

“When the enemy came up our rear guard stationed behind the fallen trees gave them a warm reception,” declared an officer of the 2

nd

West Virginia.

361

The double-shotted cannons belched fire and then limbered up and rode off, leaving torn, bleeding Confederate bodies in their wake.

362

Averell withdraws.

Averell ordered the 8

th

West Virginia to cover the retreat, to move slowly over the hill and to their horses, which were being held on the back of the slope. “This we did, and found the other regiments falling back slowly and in good order,” recounted a captain of the 8

th

West Virginia. “We came to the narrows, and formed in line of battle across the ravine, with skirmishers on the hill, and in a short time our pioneers had a barricade of timber across the road over which cavalry or artillery could not pass until removed.” The men had to search for their horses, which were scattered along the road for nearly six miles. When they found their steeds, they mounted. “By the time we reached the gap we were all mounted and moving in good order, and except the noble men that we left with sorrow, we felt that we were in condition to meet the enemy again.”

363