The Battle of White Sulphur Springs (14 page)

Read The Battle of White Sulphur Springs Online

Authors: Eric J. Wittenberg

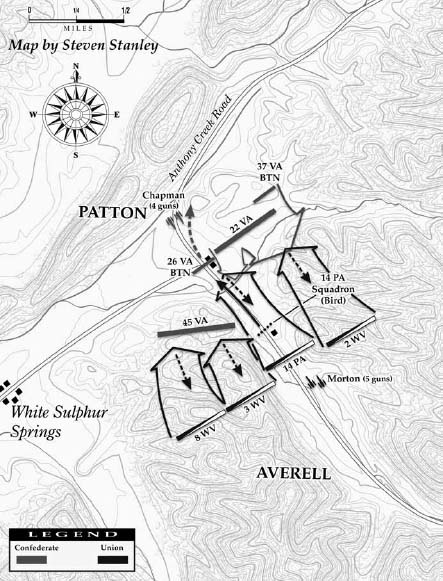

The battle rages, afternoon, August 26, 1863.

The Union troops pressed their attack, driving back the two companies of skirmishers. “It was a veritable battle-storm for about fifteen minutes, when the enemy retreated, leaving some of their dead close to our line of battle,” continued Humphreys. “A few of the left companies of the 22

nd

broke to the rear, but seeing that the rest stood their ground, and meeting Derrick's Battalion just at the right time arriving on the line of battle, they returned and fought it out there. Edgar's men stood to their work splendidly. The enemy were repulsed but not whipped.”

256

One observer noted, “The Yankees would have come out victorious if [Derrick's Battalion] hadn't got there when they did.”

257

Morton advanced his surviving guns to within six hundred yards of the Confederate barricade, where they opened on Chapman's gunners and on the Southern infantrymen. Chapman's guns responded “with great spirit and accuracy,” and “an artillery duel of great heat ensued and lasted for more than two hours, when one of our pieces was disabled and another temporarily silenced,” as Patton described the counter-battery duel that broke out.

258

“If there was ever such a thing as an artillery duel fought, it was done right there,” recalled one of Chapman's gunners. “Averell had four guns, we the same number, and were only a few hundred yards apart, and in full view; each was a target for the other, and for the space of several hours we exchanged shots as fast as it was possible to doâ¦The Federals surely had expert gunners.”

259

Sergeant H.A. Evans commanded one of Morton's guns. During the savage counter-battery duel, Evans was struck on the right side of the head by a piece of shell that exploded just over his head and was only saved by the shrapnel being deflected by striking the band of his hat. “He was knocked senseless and the bone badly shattered,” recorded his unit's historian in 1890, “seventeen pieces being taken out and it now troubles him severely.”

260

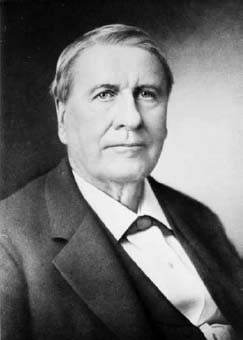

A postwar image of Major William L. McLaughlin, chief of artillery for Sam Jones's Department.

Robert Driver

.

“It affords me great pleasure to bear testimony to the efficiency with which the battery was handled, and to its marked effect upon the enemy, as attested to by the destruction of the timber in and around [Ewing's] battery, and by one of his guns being permanently disabled and another dismounted, the carriage of which was left upon the field,” wrote an admiring Major William McLaughlin, the chief of artillery for the Department of Western Virginia. “The men of the battery stood bravely and steadily by their guns, though subjected to a steady, hot, and well-directed fire from the enemy's guns, and too much credit cannot be afforded to Captain Chapman for the zeal, gallantry, and energy displayed by him throughout the engagement.”

261

In ordering an advance of his whole line, Averell sent von König with the left wing, consisting of the 2

nd

and 8

th

West Virginia, forward, and he also ordered his right wing to advance. He deployed Gibson's battalion around the Miller house and outbuildings, which sat in front of the Confederate center. “The enemy clung tenaciously to the wooded hill to their right, and Gibson's battalion was driven from the house by a regiment of the enemy which at the moment arrived upon the field,” recounted Averell. The Union general immediately had the house set

ablaze

by artillery shells, preventing the Confederates from using it as a sniper's den.

262

Lieutenant J. Calvin French of the 2

nd

West Virginia had command of a portion of his regiment's skirmish line, which was in advance of Morton's guns. While leading his troops, French received a severe wound near his right knee that distorted the joint and caused him pain for the rest of his life. His comrades rescued him and brought him back to safety before he fell into the hands of the enemy. His battle was over.

263

“The action became general and heavy,” reported Patton.

Our skirmishers in advance on the left were now hotly pressed by largely superior numbers, but under the leadership of Lieut. Col. Andrew R. Barbee, of the Twenty-second Virginia Regiment, held their ground with admirable tenacity until their ammunition was exhausted, when they fell back in good order without any confusion, and, with the exception of a part of one company which was able to rejoin its regiment, were, by the nature of the ground, forced to take position on the extreme left of our line

.

Barbee was severely wounded in the arm during this movement and was then beaten in the hip with the butt of a Federal carbine while he lay on the ground.

264

The men of the 22

nd

Virginia faced an extremely difficult situation. They held a spot out in the open without even so much as a low rail fence to protect them. The Virginians were exposed to heavy fire of musketry as well as blasts of grapeshot, shell and canister from Morton's guns, “which the enemy threw with great accuracy.”

265

Major Robert Augustus Bailey, who succeeded Barbee in command of the 22

nd

Virginia, had nothing but praise for his soldiers. “Notwithstanding the great disadvantages under which they labored, the officers and men acted most nobly, repelling the oft-repeated and daring attempts of the enemy to dislodge them,” he wrote. “The commanders of companies and their subaltern officers are entitled to much praise for their coolness under fire and the tenacity with which they held their ground.”

266

The fierce struggle between the 8

th

West Virginia and the 22

nd

Virginia hid an especially poignant story. “In the encounter between the 8

th

and the [Rebel] 22

nd

, there was something terrible, for it was really a conflict between brothers, cousins, and neighbor boys, for these two regiments were made up in the same section of country in West Virginia,” observed a captain of the 8

th

West Virginia.

267

Thirty-one-year-old Lieutenant John Gay Carr of the 22

nd

Virginia, known to his friends as Gay, a native of Charleston, had served in Colonel Patton's militia company, the Kanawha Riflemen. Carr was known as a promising young man who had exhibited the noblest qualities of a soldier both in the ranks and as an officer. “Lieutenant Gay Carr, of the Kanawha Riflemen fell with a bullet through his brain,” recounted Rand. He died on the field.

268

The popular officer was buried in the Old Stone Church Cemetery in nearby Lewisburg, and his friends and comrades later raised money to erect a handsome tree trunk monument over his grave in 1904.

269

Averell's dismounted horse soldiers made repeated charges on both the right and the left of the Confederate line, which Patton's determined defenders repulsed again and again. On the right, Baron von König and his two regiments were only able to advance a short distance through protracted, hard fighting. “Desperate efforts were made to dislodge the Forty-fifth Regiment, but the steadiness of that regiment and the courage and skill of its commander foiled them all,” reported George Patton.

270

“From the position of our battery, we could only tell what was going on by the noise,” recalled one of Chapman's gunners. “Our men said the Federals would come within twenty or thirty yards of them, and then there was a tremendous roar of musketry for a few minutes, which was always followed by the ârebel yell' by which we knew the results.”

271

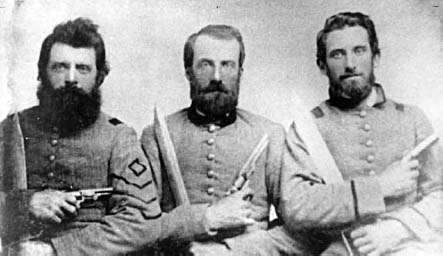

Captain Robert H. Hubble, Major William Blessing and Captain John T. Kincannon, 23

rd

Battalion Virginia Infantry.

Smith County Historical Society Museum

.

As more and more of Averell's troopers engaged, Patton grew worried that he had sufficient troops to withstand the onslaught. Luckily, he received reinforcements at the right moment. As noted earlier, Lieutenant Colonel Clarence Derrick and his 23

rd

Virginia Battalion, accompanied by about two hundred troopers of the 37

th

Battalion of Virginia Cavalry, arrived from guarding the Greenbrier Bridge. “We were roused up and hastily retraced our journey to the Dolan place, where we paused about an hour, and then pushed on rapidly to the junction of the Anthony's Creek road with the James and Kanawha turnpike, where Henry Miller had a store,” recounted one of Derrick's officers.

272

Derrick and his battalion immediately advanced to the left of the 22

nd

Virginia, first extending the Confederate line of battle. However, Derrick determined that the position could not be held, so he positioned his men some one hundred yards to the rear of the left of the line in a position that could not be outflanked to the left by Averell's men.

273

In order to reach his position, Derrick and his men were “compelled to move under a perfect storm of shot and shell, which caused some loss and some confusion, which latter was quickly remedied by that gallant officer.” Patton directed two of Derrick's companies, under command of Major William Blessing, to advance across the open field under heavy fire and took position on the left of the 22

nd

Virginia, extending the Confederate line of battle.

274

“These companies, led by Major Blessing, gallantly charged to the position assigned them through a perfect storm of shot, shell, and ball,” wrote Derrick in praise of his subordinate.

275

Patton's infantrymen stood firm. “Our infantry, when they got into line, were like a Stonewall, and held their position from start to finish,” remembered one of Chapman's artillerists. “In front of them the woods were dense with an undergrowth of bushes, except in the center where the men had no protection save an old rail fence.” These men were fighting to defend their homes and families, and they fought “like tigers, and every man of our forces acted the hero; hence any one arrogating for himself special heroism is an egotist and unworthy of credence,” he sniffed.

276

An eyewitness later said that the road “was strewn with dead and wounded soldiers.”

277

About this time, Chapman's guns ran low on ammunition. Captain Chapman told Sergeant John G. Stevens to take two limbers and go to the caissons, parked a short distance away, for a fresh supply. When he returned with the fresh ammunition, Stevens learned that Chapman had withdrawn the guns about two hundred yards to the rear. “I never knew why he did that unless it was for protection while they were not in action, and waiting for a supply of ammunition,” remembered Stevens.

278

“It then became an affair of sharpshooters along the whole line at a distance of less than 100 yards,” reported Averell. “The effort which my men had made in scaling a succession of heights on either hand had wearied them almost to exhaustion. A careful fire was kept up by small arms fire for three hours, it being almost impossible for either side to advance or retire.”