The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less (14 page)

Read The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less Online

Authors: Richard Koch

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Psychology, #Self Help, #Business, #Philosophy

Yet all this is a dreadful compromise, based on a misunderstanding. Few people stop to ask

why

the unprofitable business is so bad. Even fewer stop to think whether you could in practice, as well as in theory, have a business solely composed of the most profitable chunks and get rid of 80 percent of the overhead.

The truth is that the unprofitable business is so unprofitable

because

it requires the overheads and because having so many different chunks of business makes the organization horrendously complicated. It is equally true that the very profitable business does not require the overheads, or only a very small portion of them. You

could

have a business solely composed of the profitable business and it

could

make the same absolute returns, provided that you organized things differently.

And why is this so? The reason is the same. It is that simple is beautiful. Business people seem to love complexity. No sooner is a simple business successful than its managers pour vast amounts of energy into making it very much more complicated. But business returns abhor complexity. As the business becomes more complex, its returns fall dramatically. This is not just because more marginal business is being taken. It is also because the act of making a business more complex depresses returns more effectively than any other means known to humanity.

It follows that the process can be reversed. A complex business can be made more simple and returns can soar. All it takes is an understanding of the costs of complexity (or the value of simplicity) and courage to remove at least four-fifths of lethal managerial overhead.

SIMPLE IS BEAUTIFUL—COMPLEX IS UGLY

Those of us who believe in the 80/20 Principle will never succeed in transforming industry until we can demonstrate that simple is beautiful and why. Unless people understand this, they will never be willing to give up 80 percent of their current business and overheads.

So we need to go back to basics and revise the common view of the roots of business success. To do so, we must get involved in a current controversy over whether size in business is a help or a hindrance. By resolving this dispute, we will also be able to show why simple is beautiful.

Something very interesting, and unprecedented, is happening to our industrial structure. Since the Industrial Revolution companies have become both bigger and more diversified. Until the end of the nineteenth century, nearly all companies were national or subnational, having the vast bulk of their revenues confined to their home country; and nearly all were in just one line of business. The twentieth century has seen a series of transformations, changing the nature both of business and of our daily lives. First, thanks largely to Henry Ford’s sensationally successful quest to “democratize” the automobile, there was the burgeoning power of the assembly line, multiplying the revenues of the average firm, creating mass branded consumer goods for the first time in history, slashing the real cost of those goods, and giving more and more power to the largest enterprises. Then there was the emergence of so-called multinational enterprises, which initially took the Americas and Europe, and later the whole world, as their canvas. Next came the conglomerates, a new breed of corporation that refused to confine itself to one line of business and rapidly spread its tentacles across many industrial sectors and a myriad of products. Then the invention and refinement of the hostile takeover, fuelled equally by management ambition and the financial lubrication of leverage, gave further impetus to size. Finally, in the last 30 years of the century, the determination of industrial leaders, mainly from Japan, to seize global leadership in their priority markets and as much market share as feasible provided the final reinforcement to the cult of corporate size.

For various reasons, therefore, the first 75 years of the twentieth century witnessed a progressive and apparently unstoppable expansion in the size of industrial enterprise and, until recently, in the proportion of business activity taken by the largest firms. But in the past two decades, the latter trend has suddenly, and dramatically, gone into reverse. In 1979, the Fortune 500 largest U.S. firms accounted for nearly 60 percent of U.S. gross national product, but by the early 1990s this had slumped to just 40 percent.

Does this mean that small is beautiful?

No. This is definitely the wrong answer. There is absolutely nothing wrong with the belief long held by business leaders and strategists that scale and market share are valuable. Extra scale gives greater volume over which to spread fixed costs, especially the overhead costs that make up the lion’s share of all costs (now that factories have been made so efficient). Market share, too, helps to raise prices. The most popular firm, that with the highest market share, the best reputation and brands, and the most loyal customers, should command a price premium over lower-share competitors.

Yet why is it that larger firms are losing market share to smaller firms? And why does it happen that in practice, as opposed to theory, the advantages of scale and market share fail to translate into higher profitability? Why is it that firms often see their sales mushroom yet their returns on sales and capital actually fall, rather than rise as the theory would predict?

The cost of complexity

The most important answer is the

cost of complexity.

The problem is not extra scale, but extra complexity.

Additional scale, without additional complexity, will always give lower unit costs. To deliver to one customer more of one product or service, provided that it is exactly the same, will always raise returns.

Yet additional scale is rarely just more of the same. Even if the customer is the same, the extra volume usually comes from adapting an existing product, providing a new product, and/or adding more service. This requires expensive overhead costs that are usually hidden, but always real. And if new customers are involved it is far worse. There are high initial costs in recruiting customers and they generally have different needs to existing customers, causing even greater complexity and cost.

Internal complexity has huge hidden costs

When new business is different from existing business, even if it is only slightly different, costs tend to go up, not just pro rata with the volume increase but well ahead of it. This is because complexity slows down simple systems and requires the intervention of managers to deal with the new requirements. The cost of stopping and starting again, of communication (and miscommunication) between extra people and above all the cost of the “gaps” between people, when partially completed work is set down to await someone else’s intervention and later picked up and passed on into another gap—all these costs are horrendous and all the more insidious because they are largely invisible. If the communication needs to straddle different divisions, buildings, and countries, the result is even worse.

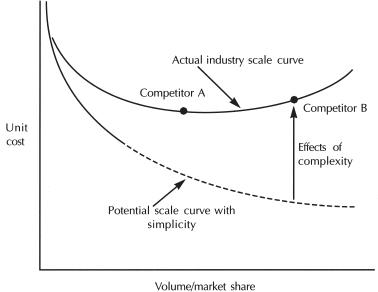

How this works is shown in Figure 31. Competitor B is larger than competitor A, yet has higher costs. This is not because the scale curve—additional volume equals lower costs—doesn’t work. Rather, it is because B’s extra volume has been bought at the cost of higher complexity. The effect of this is massive and much greater than the additional cost that is visible relative to A. The scale curve operates, but its benefits are overturned by the extra complexity.

Figure 31 The cost of complexity

SIMPLE IS BEAUTIFUL EXPLAINS THE 80/20 PRINCIPLE

Understanding the cost of complexity allows us to take a major leap forward in the debate about corporate size. It is not that small is beautiful. All other things being equal, big is beautiful. But all other things are not equal. Big is only ugly and expensive because it is complex. Big can be beautiful. But it is simple that is

always

beautiful.

Even management scientists are belatedly realizing the value of simplicity. A recent careful study of 39 middle-sized German companies, led by Gunter Rommel,

2

found that only one characteristic differentiated the winners from the less successful firms: simplicity. The winners sold a narrower range of products to fewer customers and also had fewer suppliers. The study concludes that a simple organization was best at selling complicated products.

This mental breakthrough helps to explain why and how the seemingly outrageous claims of the 80/20 Principle, applied to corporate profits, can actually be true. A fifth of revenues can produce four-fifths of profits. The top 20 percent of revenues can be 16 times more profitable than the bottom 20 percent (or, where the bottom 20 percent makes a loss, infinitely more profitable!). Simple is beautiful explains a large part of why the 80/20 Principle works:

• Simple and pure market share is much more valuable than has previously been recognized. The returns from pure scale have been obscured by the cost of complexity associated with impure scale. And different chunks of business have usually had different competitors and different relative strength vis-à-vis those competitors. Where a business is dominant in its narrowly defined niche, it is likely to make several times the returns earned in niches where one faces a dominant competitor (the mirror image).

• Parts of the business that are mature and simple can be amazingly profitable. Cutting the number of products, customers, and suppliers usually leads to higher profits, partly because you can have the luxury of just focusing on the most profitable activities and customers, but partly also because the costs of complexity—in the form of overheads and management—can be slashed.

• In different products, firms often have differences in the extent to which they buy in goods and services from the outside (in the jargon, outsourcing). Outsourcing is a terrific way to cut complexity and costs. The best approach is to decide which is the part of the value-adding chain (R&D/manufacturing/ distribution/selling/marketing/servicing) where your company has the greatest comparative advantage—and then ruthlessly outsource everything else. This can take out most of the costs of complexity and enable dramatic reductions in head count, as well as speeding up the time it takes you to get a product to market. The result: much lower costs and often significantly higher prices too.

• It can enable you to do away with all central functions and costs. If you are just in one line of business, you don’t need a head office, regional head offices, or functional offices. And the abolition of the head office can have an electric effect on profits. The key problem with head offices is not their cost; it is the way they take away real responsibility and initiative from those who do the work and add the value to customers. For the first time, corporations can center themselves around customer needs rather than around the management hierarchy.

Before the head office is abolished, different chunks of business attract different degrees of head office cost and interference. The most profitable products and services are usually those that are left to get on with their own life without any “help” from the center. This is why, when 80/20 profitability exercises have been carried out, executives are often staggered to learn that the most neglected areas are the most profitable. It is no accident. (And one of the unfortunate byproducts of 80/20 Analysis is sometimes that the most profitable areas get a lot more attention from managers at the top. As a result, they can begin to drop down the profitability league table.)

• Finally, where a chunk of business is simple, the chances are that it is closer to the customer. There is less management to get in the way. Customers can be listened to and feel that they are important. People are willing to pay a lot more for this. For customers, the quest for self-importance is at least as important as the quest for value. Simplicity raises prices as well as lowering costs.

CONTRIBUTION TO OVERHEAD: ONE OF THE LAMEST EXCUSES FOR INACTION

Frequently, managers faced with the results of 80/20 Analysis protest that they cannot just focus on the most profitable segments. They point out that the less profitable segments, and even the loss-making segments, make a positive contribution to overheads. This is one of the lamest and most self-serving defense mechanisms ever contrived.

If you focus on the most profitable segments, you can grow them surprisingly fast—nearly always at 20 percent a year and sometimes even faster. Remember that the initial position and customer franchise are strong, so it’s a lot easier than growing the business overall. The need for overhead coverage from unprofitable segments can disappear pretty quickly.