The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less (5 page)

Read The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less Online

Authors: Richard Koch

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Psychology, #Self Help, #Business, #Philosophy

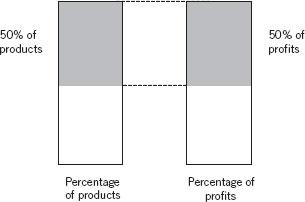

The 80/20 numbers are only a benchmark, and the real relationship may be more or less unbalanced than 80/20. The 80/20 Principle asserts, however, that in most cases the relationship is much more likely to be closer to 80/20 than to 50/50. If all of the products in our example made the same profit, then the relationship would be as shown in Figure 4.

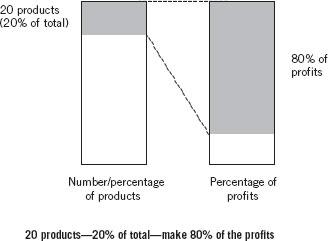

Figure 3 A typical 80/20 pattern

The curious but crucial point is that, when such investigations are conducted, Figure 3 turns out to be a much more typical pattern than Figure 4. Nearly always, a small proportion of total products produces a large proportion of profits.

Figure 4 An unusual 50/50 pattern

Of course, the exact relationship may not be 80/20. 80/20 is both a convenient metaphor and a useful hypothesis, but it is not the only pattern. Sometimes, 80 percent of the profits come from 30 percent of the products; sometimes 80 percent of the profits come from 15 percent or even 10 percent of the products. The numbers compared do not have to add up to 100, but the picture usually looks unbalanced, much more like Figure 3 than Figure 4.

It is perhaps unfortunate that the numbers 80 and 20 add up to 100. This makes the result look elegant (as, indeed, would a result of 50/50, 70/30, 99/1, or many other combinations) and it is certainly memorable, but it makes many people think that we are dealing with just one set of data, one 100 percent. This is not so. If 80 percent of people are right-handed and 20 percent are left-handed, this is not an 80/20 observation. To apply the 80/20 Principle you have to have two sets of data, both adding up to 100 per cent, and one measuring a variable quantity owned, exhibited, or caused by the people or things making up the other 100 percent.

WHAT THE 80/20 PRINCIPLE CAN DO FOR YOU

Every person I have known who has taken the 80/20 Principle seriously has emerged with useful, and in some cases life-changing, insights. You have to work out your own uses for the principle: they will be there if you look creatively. Part Three (Chapters 9 to 15) will guide you on your odyssey, but I can illustrate with some examples from my own life.

How the 80/20 Principle has helped me

When I was a raw student at Oxford, my tutor told me never to go to lectures. “Books can be read far faster,” he explained. “But never read a book from cover to cover, except for pleasure. When you are working, find out what the book is saying much faster than you would by reading it through. Read the conclusion, then the introduction, then the conclusion again, then dip lightly into any interesting bits.” What he was really saying was that 80 percent of the value of a book can be found in 20 percent or fewer of its pages and absorbed in 20 percent of the time most people would take to read it through.

I took to this study method and extended it. At Oxford there is no system of continuous assessment, and the class of degree earned depends entirely on finals, the examinations taken at the end of the course. I discovered from the “form book,” that is by analyzing past examination papers, that at least 80 percent (sometimes 100 percent) of an examination could be well answered with knowledge from 20 percent or fewer of the subjects that the exam was meant to cover. The examiners could therefore be much better impressed by a student who knew an awful lot about relatively little, rather than a fair amount about a great deal. This insight enabled me to study very efficiently. Somehow, without working very hard, I ended up with a congratulatory First Class degree. I used to think this proved that Oxford dons were gullible. I now prefer to think, perhaps improbably, that they were teaching us how the world worked.

I went to work for Shell, serving my time at a dreadful oil refinery. This may have been good for my soul, but I rapidly realized that the best-paying jobs for young and inexperienced people such as I lay in management consultancy. So I went to Philadelphia and picked up an effortless MBA from Wharton (scorning the boot-camp style so-called learning experience from Harvard). I joined a leading U.S. consultancy that on day one paid me four times what Shell had paid me when I left. No doubt 80 percent of the money to be had by people of my tender age was concentrated in 20 percent of the jobs.

Since there were too many colleagues in the consultancy who were smarter than me, I moved to another U.S. strategy “boutique.” I identified it because it was growing faster than the firm I had joined, yet had a much smaller proportion of really smart people.

Who you work for is more important than what you do

Here I stumbled across many paradoxes of the 80/20 Principle. Eighty percent of the growth in the strategy consultancy industry—then, as now, growing like gangbusters—was being appropriated by firms that then had, in total, fewer than 20 percent of the industry’s professional staff. Eighty percent of rapid promotions were also available in just a handful of firms. Believe me, talent had very little to do with it. When I left the first strategy firm and joined the second, I raised the average level of intelligence in both.

Yet the puzzling thing was that my new colleagues were more effective than my old ones. Why? They didn’t work any harder. But they followed the 80/20 Principle in two key ways. First, they realized that for most firms, 80 percent of profits come from 20 percent of clients. In the consulting industry that means two things: large clients and long-term clients. Large clients give large assignments, which means you can use a higher proportion of lower-cost, younger consultants. Long-term client relationships create trust and raise the cost to the client of switching to another consulting firm. Long-term clients tend not to be price sensitive.

In most consulting firms, the real excitement comes from winning new clients. In my new firm, the real heroes were those who worked on the largest existing clients for the longest possible time. They did this by cultivating the top bosses of those client corporations.

The second key insight the consulting firm had was that in any client, 80 percent of the results available would flow from concentrating on the 20 percent of most important issues. These were not necessarily the most interesting ones from a curious consultant’s viewpoint. But, whereas our competitors would look superficially at a whole range of issues and then leave them for the client to act (or not) on the recommendations, we kept plugging away at the most important issues until we had bludgeoned the client into successful action. The clients’ profits often soared as a result, as did our consulting budgets.

Are you working to make others rich or is it the reverse?

I soon became convinced that, for both consultants and their clients, effort and reward were at best only loosely linked. It was better to be in the right place than to be smart and work hard. It was best to be cunning and focus on results rather than inputs. Acting on a few key insights produced the goods. Being intelligent and hard working did not. Sadly, for many years, guilt and conformity to peer-group pressure kept me from fully acting on this lesson; I worked far too hard.

By this time, the consulting firm had several hundred professional staff and about 30 people, including myself, who were called partners. But 80 percent of the profits went to one man, the founder, even though numerically he constituted less than 4 percent of the partnership and a fraction of 1 percent of the consulting force.

Instead of continuing to enrich the founder, two other junior partners and I spun off to set up our own firm doing exactly the same thing. We in turn grew to have hundreds of consultants. Before long, although the three of us, on any measure, did less than 20 percent of the firm’s valuable work, we enjoyed over 80 percent of the profits. This, too, caused me guilt. After six years I quit, selling my shares to the other partners. At this time, we had doubled our revenues and profits every year, and I was able to secure a good price for my shares. Shortly after, the recession of 1990 hit the consulting industry. Although I will counsel you later to give up guilt, I was lucky with my guilt. Even those who follow the 80/20 Principle need a bit of luck, and I have always enjoyed far more than my share.

Wealth from investment can dwarf wealth from working

With 20 percent of the money received, I made a large investment in the shares of one corporation, Filofax. Investment advisers were horrified. At the time I owned about 20 shares in quoted public companies, but this one stock, 5 percent of the number of shares I owned, accounted for about 80 percent of my portfolio. Fortunately, the proportion proceeded to grow still further, as over the next three years Filofax shares multiplied several times in value. When I sold some shares, in 1995, it was at nearly 18 times the price I had paid for my first stake.

I made two other large investments, one in a start-up restaurant called Belgo and the other in MSI, a hotel company that at the time owned no hotels. Together, these three investments at cost comprised about 20 percent of my net worth. But they have accounted for more than 80 percent of my subsequent investment gains and now comprise over 80 percent of a much larger net worth.

As Chapter 14 will show, 80 percent of the increase in wealth from most long-term portfolios comes from fewer than 20 percent of the investments. It is crucial to pick this 20 percent well and then concentrate as much investment as possible into it. Conventional wisdom is not to put all your eggs in one basket. 80/20 wisdom is to choose a basket carefully, load all your eggs into it, and then watch it like a hawk.

HOW TO USE THE 80/20 PRINCIPLE

There are two ways to use the 80/20 Principle, as shown in Figure 5.

Traditionally, the 80/20 Principle has required 80/20 Analysis, a quantitative method to establish the precise relationship between causes/input/effort and results/outputs/rewards. This method uses the possible existence of the 80/20 relationship as a hypothesis and then gathers the facts so that the true relationship is revealed. This is an empirical procedure which may lead to any result ranging from 50/50 to 99.9/0.1. If the result does demonstrate a marked imbalance between inputs and outputs (say a 65/35 relationship or an even more unbalanced one), then normally action is taken as a result (see below).

Figure 5 Two ways to use the 80/20 Principle

A new and complementary way to use the 80/20 Principle is what I call 80/20 Thinking. This requires deep thought about any issue that is important to you and asks you to make a judgment on whether the 80/20 Principle is working in that area. You can then act on the insight. 80/20 Thinking does not require you to collect data or actually test the hypothesis. Consequently, 80/20 Thinking may on occasion mislead you—it is dangerous to assume, for example, that you already know what the 20 percent is if you identify a relationship—but I will argue that 80/20 Thinking is much less likely to mislead you than is conventional thinking. 80/20 Thinking is much more accessible and faster than 80/20 Analysis, although the latter may be preferred when the issue is extremely important and you find it difficult to be confident about an estimate.