The 30 Day MBA (15 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

CASE STUDY

Â

Ocado: cash box placing

Ocado, which sells food sourced from supermarket operator Waitrose (part of John Lewis), launched an initial public offering (IPO) in 2010 putting a value of between £1 billion and £1.1 billion on the business. Not bad for a business showing losses in the preceding three years of £22.5 million, £43.5 million and £45.5 million, an improving trend, albeit a fairly shallow one.

It was long known that the company's strategy called for a voracious consumption of cash and in various rounds of fundraising the company had already raised just short of £300 million, more than any other European internet start-up.

By November 2012 Ocado's business model had not delivered the goods.

Shareholders grabbing a slice of the action in July 2010's 180p-a-share float had lost almost two-thirds of their money. Financial engineering to the rescue: the business urgently needed another £35 million or so to keep the show on the road and there was no chance of existing shareholders or their bankers stumping up more cash. Goldman Sachs came to the rescue with a little known money spinner, Cash Box Placing, a strategy that neatly skirts past the pre-emption requirements of Companies Act 2006 requiring all shareholders to be treated equally and allowing the use of a special purpose unlisted vehicle to warehouse the funds.

The only asset of the special purpose vehicle, in this case Weir Developments, is cash. The cash is generated by a subscription of shares by Goldman who are then able to finance their commitment to fund the subscription price on the shares out of the proceeds of placing the company's shares at a highly preferential price â in this case 64p. The net result is that shareholders who are not invited by Goldman or joint-bookrunner Numis Securities to take part in the placing get their shareholding diluted by the addition of new shareholders. Worse still they get no say in the matter yet have to fund £1 million of fees to engineer the deal.

Initial public offer (IPO) â criteria for getting a stock market listing

The rules vary from market to market but these are the conditions that are likely to apply to get a company listed on an exchange:

- Getting listed on a major stock exchange calls for a track record of making substantial profits with decent seven-figure sums being made in the year you plan to float, as this process is known. A listing also calls for a large proportion, usually at least 25 per cent, of the company's shares to be put up for sale at the outset. In addition, you would be expected to have 100 shareholders now and be able to demonstrate that 100 more will come on board as a result of the listing.

- As you draw up your flotation plan and timetable you should have the following matters in mind:

â Advisers: You will need to be supported by a team which will include a sponsor, stockbroker, reporting accountant and solicitor. These should be respected firms, active in flotation work and familiar with the company's type of business. You and your company may be judged by the company you keep, so choose advisers of good repute and make sure that the personalities work effectively together. It is very unlikely that a small local firm of accountants, however satisfactory, will be up to this task.

â

Sponsor: You will need to appoint a financial institution, usually a merchant banker, to fill this important role. If you do not already have a merchant bank in mind, your accountant will offer guidance. The job of the sponsor is to coordinate and drive the project forward.â Timetable: It is essential to have a timetable for the final months during the run-up to a float â and to adhere to it. The company's directors and senior staff will be fully occupied in providing information and attending meetings. They will have to delegate and there must be sufficient backup support to ensure that the business does not suffer.

â Management team: A potential investor will want to be satisfied that your company is well managed, at board level and below. It is important to ensure succession, perhaps by offering key directors and managers service agreements and share options. It is wise to draw on the experience of well-qualified non-executive directors.

â Accounts: The objective is to have a profit record which is rising but, in achieving this, you will need to take into account directors' remuneration, pension contributions and the elimination of any expenditure which might be acceptable in a privately owned company but would not be acceptable in a public company, namely excessive perks such as yachts, luxury cars, lavish expense accounts and holiday homes.

Accounts must be consolidated and audited to appropriate accounting standards and the audit reports must not contain any major qualifications. The auditors will need to be satisfied that there are proper stock records and a consistent basis of valuing stock during the years prior to flotation. Accounts for the last three years will need to be disclosed and the date of the last accounts must be within six months of the issue.

AIM

London's Alternative Investment Market (AIM) was formed in the mid-to-late 1990s specifically to provide risk capital for new rather than established ventures. AIM raised £15.7bn in 2007 â a 76 per cent leap from the previous year â and a record number of companies floated on the exchange, bringing the total to 1,634.

AIM is particularly attractive to any dynamic company of any size, age or business sector that has rapid growth in mind. The smallest firm on AIM entered at under £1 million capitalization and the largest at over £500 million. The formalities are minimal, but the costs of entry are high and you must have a nominated adviser, such as a major accountancy firm, stockbroker or banker. The survey showed that costs of floating on the junior market is around 6.5 per cent of all funds raised and companies valued at less than £2m can expect to shell out a quarter of funds raised

in costs alone. The market is regulated by the London Stock Exchange (

www.londonstockexchange.com

> For companies and advisers > AIM).

You can check out all the world stock markets from Australia to Zagreb on Stock Exchanges World Wide Links (

www.tdd.lt/slnews/Stock_Exchanges/Stock.Exchanges.htm

), maintained by Aldas Kirvaitis of Lithuania, and at World Wide Tax.com (

www.worldwide-tax.com

> World Stock Exchanges). Once in the stock exchange website, almost all of which have pages in English, look out for a term such as âListing Center', âListing' or âRules'. There you will find the latest criteria for floating a company on that particular exchange.

PLUS â a market fails

One rung down from AIM was PLUS-Quoted Market whose roots lie in the market formerly known as Ofex. It began life in November 2004 and was granted Recognised Investment Exchange (RIE) status by the Financial Services Authority (FSA) in 2007. Aimed at smaller companies wanting to raise up to £10 million it draws on a pool of capital primarily from private investors. The market is regulated, but requirements are not as stringent as those of AIM or the main market and the costs of flotation and ongoing costs are lower. Keycom used this market to raise £4.4 million in September 2008 to buy out a competitor to give them a combined contract to provide broadband access to 40,000 student rooms in UK universities. There are 174 companies quoted on PLUS with a combined market capitalization of £2.3 billion. Even in 2009/10, a particularly bad period for stock market activity, 30 companies applied for entry to PLUS and 18 were admitted. But in 2012 after a fruitless attempt to sell up, the exchange closed leaving shareholders and companies in a less than desirable position. The lesson here is that there is only so far up the risk curve you can go and still have sufficient buyers and sellers to create a market.

Share buyback

Companies can buy back their shares, which reduces the number of shares outstanding, giving each remaining shareholder a larger percentage ownership of the company. This is usually considered a sign that the company's management believes its share price is undervalued. Other reasons for buybacks include putting unused cash to use, raising earnings per share and obtaining stock for employee stock option plans or pension plans.

A number of financing methods straddle the debt and equity boundary. These try to mitigate taking a bit more risk for the potential of a bit more return than would be usual with debt financing. But they also limit the upside that might be expected from pure equity, which would retain all of any increase in value from the outset:

- Convertible preference shares operate like preference shares, in that their holders rank before ordinary shareholders for dividend payment, or return of funds in the case of failure. They also have the option, at some specified date in the future, to convert to ordinary shares and so enjoy all of any increase in value.

- Mezzanine finance has one or all of these characteristics: it ranks after other forms of debt, but before equity, for any payout in the event of a business failing; it pays higher, often significantly higher, interest than other debt; it can be held for up to 10 years; it can be converted into ordinary shares. It is popular with VCs for management buyouts.

Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding business finance is a new game-changing concept that puts the power firmly into the hands of entrepreneurs looking to raise finance. Instead of one large investor putting money into a business, larger numbers of smaller investors contribute as little as £10 each to raise the required capital. Crowdcube, the first UK-based crowdfunding website, has now teamed up with Startups.co.uk so entrepreneurs will be able to both access information on raising finance and have direct access to an innovative way to solve the problem from one site (

www.crowdcube.com/partner/startups

).

Crowdcube was the first crowdfunding website in the world to enable the public to invest in and receive shares in UK companies, and has more than 10,000 registered members currently seeking investment opportunities. The platform has already raised more than £3 million for small businesses through its principal site, and hosted the world's first £1 million crowdfunding deal in November 2011. The range of businesses that have used this financing method is wide and getting wider. Darlington Football Club raised £291,450 from 722 investors over 14 days through Crowdcube to help fend off closure after going into liquidation. Oil supplier Universal Fuels has raised £100,000 through Crowdcube, making founder Oliver Morgan the youngest entrepreneur to successfully raise investment through the process.

Grants

Government agencies at both national and local government level as well as some extra-governmental bodies such as the EU offer grants, effectively free or nearly free money in return for certain behaviour. It may be to encourage research into a particular field, stimulate innovation or employment or to persuade a company to locate in a particular area. Grants are constantly being introduced (and withdrawn), but there is no system that lets you know automatically. You have to keep yourself informed.

You can find out about international grants and funding at Proposalwriter.com (

www.proposalwriter.com/intgrants.html

), as well as advice on writing a proposal.

Grants.Gov (

www.grants.gov

) is a guide to how to apply for over 1,000 federal government grants in the United States.

A business needs to keep track of how much it is paying for the capital it uses, as that is the minimum hurdle rate for any investment it may make. Also, it needs to be aware that if new money being raised is more costly than that already in the business, it will only be profitable if it raises the hurdle rate for new projects accordingly.

Cost of debt

This can be very straightforward. If a company takes out a bank loan at a fixed rate of interest of say, 8 per cent, then this is the cost before any tax relief. Taking tax relief at 40 per cent into account, the net cost of debt comes down to 4.8 per cent. In the case of a public offer for bonds or debentures, the rate of interest which has to be paid on new loans to get them taken up by investors at par can be regarded as the cost of borrowed capital.

Cost of equity

Put simply, the cost of equity is the return shareholders expect the company to earn on their money. It is their estimation, often not scientifically calculated, of the rate of return that will be obtained both from future dividends and an increased share value.

Dividend valuation model

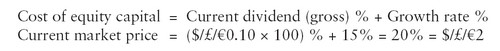

One approach to finding the cost of equity is to take the current gross dividend yield for a company and add the expected annual growth.

Example

For example, XYZ plc has forecast payment of a gross equivalent dividend of 10p on each ordinary share in the coming year. The company's shares are quoted on the Stock Exchange and currently trade at $/£/â¬2.00. Growth of profits and dividends has averaged 15 per cent over the past few years. The cost of equity for XYZ plc can be calculated as: