The 30 Day MBA (12 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

£/$/⬠| |

Unit cost breakdown | 3.00 |

Variable costs | 1.43 (£/$/â¬10,000 fixed costs ÷ 7,000 units) |

Contribution to fixed costs | |

Contribution to meet profit objective | 1.43 (£/$/â¬10,000 prof object ÷ 7,000 units) |

Selling price | 5.86 |

As all fixed costs are met on the 7,000 units sold (or to be sold), the remaining units can be sold at a price that covers both variable costs and the profitability contribution, so you can negotiate at the same level of profitability, down to £/$/â¬4.43, just under 25 per cent off the current selling price. However, any selling price above the £/$/â¬3.00 variable cost will generate extra profits, but these sales will be at the expense of your profit margin. A lower profit margin in itself is not necessarily a bad thing if it results in a higher return on capital employed, but first you must do the sums. There is a great danger with negotiating orders at marginal costs, as these costs are called, in that you do not achieve your break-even point and so perpetuate losses.

Dealing with multiple products and services

The examples used to illustrate the break-even profit point model were fairly simple. Few if any businesses sell only one product or service, so a more general equation may be more useful to deal with real world situations.

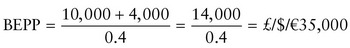

In such a business, to calculate your break-even point you must first establish your gross profit. This is calculated by deducting the money paid out to suppliers from the money received from customers. For example, if you are aiming for a 40 per cent gross profit, expressed in decimals as 0.4, your fixed costs are £/$/â¬10,000 and your overall profit objective is £/$/â¬4,000, then the sum will be as follows:

So, to reach the target you must achieve a £/$/â¬35,000 turnover. (You can check this out for yourself: look back to the previous example where the BEPP was 7,000 units and the selling price was £/$/â¬5 each. Multiplying those figures out gives a turnover of £/$/â¬35,000. The gross profit in that example was 2/5, or 40 per cent, also.)

- Where business gets its money

- The difference between debt and shareholders' investment

- Understanding the role of private equity

- Floating on a stock market

- Calculating the cost of capital

- Budgeting for the future

T

he dividing line between accounting and finance is blurred. In basic terms accounting is considered to be everything concerned with the process of recording financial events and ensuring that such recordings are in compliance with the prevailing rules. Finance is the area concerned with where the money to run a business actually comes from in order to be accounted for. In order to be able to understand and interpret the accounts using such tools as ratios you need a reasonable grasp of both these areas, though the ratios themselves are generally considered to be in the accounting domain. In this book the accounting and finance chapters have been placed next to each other to eliminate the need for debate on boundaries.

In many business schools you will find an array of options in addition to the core elements of this discipline. At the London Business School, for example, you will find asset pricing, corporate finance, hedge funds, corporate governance, investments, mergers and acquisitions, capital markets and international finance on the menu. Members of the Finance Group also run the BNP Paribas Hedge Fund Centre, the Centre for Corporate Governance, the Private Equity Institute and the London Share Price Database. At Cass Business School, City of London, you will find options on behavioural finance, dealing with financial crime, and derivatives. In this chapter there is all that you would find in the core teaching that you need to understand and sufficient to move on to more esoteric aspects of finance should the need ever arise.

There are many sources of funds available to businesses; however, not all of them are equally appropriate to all businesses at all times. These different sources of finance carry very different obligations, responsibilities and opportunities for profitable business. Having some appreciation of these differences will enable managers and directors to make an informed choice.

Most businesses initially, and often until they go public, floating their shares on a stock market, confine their financial strategy to bank loans, either long term or short term, viewing the other financing methods as either too complex or too risky. In many respects the reverse is true. Almost every finance source other than banks will to a greater or lesser extent share some of the risks of doing business with the recipient of the funds.

Debt vs equity

Despite the esoteric names â debentures, convertible loan stock, preference shares â businesses have access to only two fundamentally different sorts of money. Equity, or owner's capital, including retained earnings, is money that is not a risk to the business. If no profits are made, then the owner and other shareholders simply do not get dividends. They may not be pleased, but they cannot usually sue, and even where they can sue, the advisers who recommended the share purchase will be first in line.

Debt capital is money borrowed by the business from outside sources; it puts the business at financial risk and is also risky for the lenders. In return for taking that risk they expect an interest payment every year, irrespective of the performance of the business. High gearing is the name given when a business has a high proportion of outside money to inside money. High gearing has considerable attractions to a business that wants to make high returns on shareholders' capital.

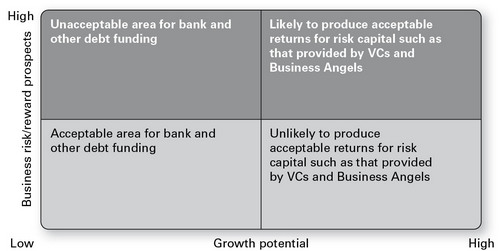

Figure 2.1

shows the funding appetite of various sources of funds. VCs, business angels and indeed any source of share capital will only be attracted to propositions that combine high growth potential with a high risk/reward potential. Banks and other lenders will be attracted to almost the opposite profile, looking instead to a stable less risky proposition that at least offers some security to the capital sum they are putting up.

FIGURE 2.1

Â

Funding appetite

Table 2.1

shows an example of a business that is assumed to need $/£/â¬60,000 capital to generate $/£/â¬10,000 operating profits. Four different capital structures are considered. They range from all share capital (no gearing) at one end to nearly all loan capital at the other. The loan capital has to be âserviced', that is, interest of 12 per cent has to be paid. The loan itself can be relatively

indefinite, simply being replaced by another one at market interest rates when the first loan expires.

TABLE 2.1

The effect of leverage/gearing on shareholders' returns

No gearing | Average gearing | High gearing | Very high gearing | ||

N/A | 1:1 | 2:1 | 3:1 | ||

Capital structure | $/£/⬠| $/£/⬠| $/£/⬠| $/£/⬠| |

Share capital | 60,000 | 30,000 | 20,000 | 15,000 | |

Loan capital (at 12%) | â | 30,000 | 40,000 | 45,000 | |

Total capital | 60,000 | 60,000 | 60,000 | 60,000 | |

Profits | |||||

Operating profit | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 | |

Less interest on loan | None | 3,600 | 4,800 | 5,400 | |

Net profit | 10,000 | 6,400 | 5,200 | 4,600 | |

Return on share capital | = | 10,000 | 6,400 | 5,200 | 4,400 |

60,000 | 30,000 | 20,000 | 15,000 | ||

= | 16.6% | 21.3% | 26% | 30.7% | |

Times interest earned | = | N/A | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 |

3,600 | 4,800 | 5,400 | |||

= | N/A | 2.8 times | 2.1 times | 1.8 times |

Following the tables through, you can see that return on the shareholders' money (arrived at by dividing the profit by the shareholders' investment and multiplying by 100 to get a percentage) grows from 16.6 to 30.7 per cent by virtue of the changed gearing. If the interest on the loan were lower, the ROSC, the term used to describe return on shareholders' capital, would be even more improved by high gearing, and the higher the interest, the lower the relative improvement in ROSC. So in times of low interest, businesses tend to go for increased borrowings rather than raising more equity, that is, money from shareholders.

At first sight this looks like a perpetual profit-growth machine. Naturally, shareholders and those managing a business whose bonus depends on shareholders' returns would rather have someone else âlend' them the money for the business than ask shareholders for more money, especially if by doing so they increase the return on investment. The problem comes if the business does not produce $/£/â¬10,000 operating profits. Very often a drop in sales of 20 per cent means profits are halved. If profits were halved in this example, the business could not meet the interest payments on its loan. That would make the business insolvent, and so not in a âsound financial position'; in other words, failing to meet one of the two primary business objectives.

Bankers tend to favour 1 : 1 gearing as the maximum for a business, although they have been known to go much higher. As well as looking at the gearing, lenders will study the business's capacity to pay interest. They do this by using another ratio called âtimes interest earned'. This is calculated by dividing the operating profit by the loan interest. It shows how many times the loan interest is covered, and gives the lender some idea of the safety margin. The ratio for this example is given at the end of

Table 2.1

. Once again rules are hard to make, but much less than 3Ã interest earned is unlikely to give lenders confidence. (See

Chapter 1

for a comprehensive explanation of the use of ratios.)

Towards the lower-risk end of the financing spectrum are the various organizations that lend money to businesses. They all try hard to take little or no risk, but expect some reward irrespective of performance. They want interest payments on money lent, usually from day one, though sometimes they are content to roll interest payments up until some future date. While they hope the management is competent, they are more interested in securing a charge against any assets the business or its managers may own. At the end of the day they want all their money back. It would be more prudent to think of these organizations as people who will help you turn a proportion

of an illiquid asset, such as property, stock in trade or customers who have not yet paid up, into a more liquid asset such as cash, but of course at some discount.

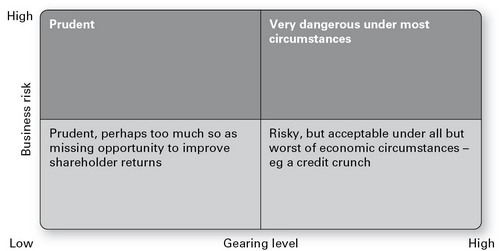

Any decisions about gearing levels have to be taken with the level of business risk involved. Certain categories of venture are intrinsically more risky than others. Businesses selling staple food products where little innovation is required are generally less prone to face financial difficulties than, say, internet start-ups, where the technology may be unproven with a short shelf life and the markets themselves uncertain. See

Figure 2.2

below.

FIGURE 2.2

Â

Risk and leverage/gearing

Banks are the principal, and frequently the only, source of finance for 9 out of every 10 unquoted businesses. Firms around the world rely on banks for their funding. In the UK, for example, they have borrowed nearly £55 ($86/â¬62) billion from the banks, a substantial rise over the past few years. When this figure is compared with the £48 ($75/â¬54) billion that firms have on deposit at any one time, the net amount borrowed is around £7 billion.

Bankers, and indeed any other sources of debt capital, are looking for asset security to back their loan and provide a near-certainty of getting their money back. They will also charge an interest rate that reflects current market conditions and their view of the risk level of the proposal; usually anything from 0.25 per cent to upwards of 3 or 4 per cent for more risky or smaller firms.

Bankers like to speak of the âfive Cs' of credit analysis, factors they look at when they evaluate a loan request. When applying to a bank for a loan, be prepared to address the following points:

- Character: Bankers lend money to borrowers who appear honest and who have a good credit history. Before you apply for a loan, it makes sense to obtain a copy of your credit report and clean up any problems.

- Capacity: This is a prediction of the borrower's ability to repay the loan. For a new business, bankers look at the business plan. For an existing business, bankers consider financial statements and industry trends.

- Collateral: Bankers generally want a borrower to pledge an asset that can be sold to pay off the loan if the borrower lacks funds.

- Capital: Bankers scrutinize a borrower's net worth, the amount by which assets exceed debts.

- Conditions: Whether bankers give a loan can be influenced by the current economic climate as well as by the amount.