The 30 Day MBA (8 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

Before we can measure and analyse anything about a business's accounts we need some idea of what level or type of performance a business wants to achieve. All businesses have three fundamental objectives in common, which allow us to see how well (or otherwise) they are doing.

Making a satisfactory return on investment

The first of these objectives is to make a satisfactory return (profit) on the money invested in the business.

It is hard to think of a sound argument against this aim. To be satisfactory the return must meet four criteria:

- It must give a fair return to shareholders, bearing in mind the risk they are taking. If the venture is highly speculative and the profits are less than bank interest rates, your shareholders (yourself included) will not be happy.

- You must make enough profit to allow the company to grow. If a business wants to expand sales it will need more working capital and eventually more space or equipment. The safest and surest source of new money for this is internally generated profits, retained in the business: reserves. (A business has three sources of new money: share capital or the owner's money; loan capital, put up by banks etc; retained profits, generated by the business.)

- The return must be good enough to attract new investors or lenders. If investors can get a greater return on their money in some other comparable business, then that is where they will put it.

- The return must provide enough reserves to keep the real capital intact. This means that you must recognize the impact inflation has on the business. A business retaining enough profits each year to meet a 3 per cent growth is actually contracting by 1 per cent if inflation is running at 4 per cent.

Maintaining a sound financial position

As well as making a satisfactory return, investors, creditors and employees expect the business to be protected from unnecessary risks. Clearly, all businesses are exposed to market risks: competitors, new products and price changes are all part of a healthy commercial environment. The sorts of unnecessary risk that investors and lenders are particularly concerned about are high financial risks, such as overtrading.

Cash-flow problems are not the only threat to a business's financial position. Heavy borrowing can bring a big interest burden to a small business, especially when interest rates rise unexpectedly. This may be acceptable when sales and profits are good; however, when times are bad, bankers, unlike shareholders, cannot be asked to tighten their belts â they expect to be paid all the time. So the position audit is not just about profitability, but about survival capabilities and the practice of sound financial disciplines.

Achieving growth

Making profit and surviving are insufficient achievements in themselves to satisfy either shareholders or directors or ambitious MBAs â they want the business to grow too. But they do not just want the number of people they employ to get larger, or the sales turnover to rise, however nice they may be. They want the firm to become more efficient, to gain economies of scale and to improve the quality of profits.

Ratios used in analysing company accounts are clustered under five headings and are usually referred to as âtests':

- tests of profitability;

- tests of liquidity;

- tests of solvency;

- tests of growth;

- market tests.

The profit and loss account and balance sheet in Tables 1.7 and 1.8 will be used, where possible, to illustrate these ratios.

Tests of profitability

There are six ratios used to measure profit performance. The first four profit ratios are arrived at using only the profit and loss account and the other two use information from both that account and the balance sheet.

Gross profit

This is calculated by dividing the gross profit by sales and multiplying by 100. In this example the sum is 30,000 / 60,000 Ã 100 = 50 per cent. This is a measure of the value we are adding to the bought-in materials and services we need to âmake' our product or service; the higher the figure the better.

Operating profit

This is calculated by dividing the operating profit by sales and multiplying by 100. In this example the sum is 8,700 / 60,000 Ã 100 = 14.5 per cent. This is a measure of how efficiently we are running the business, before taking account of financing costs and tax. These are excluded as interest and tax rates change periodically and are outside our direct control. Excluding them makes it easier to compare one period with another or with another business. Once again the rule here is the higher the figure the better.

Net profit before and after tax

Dividing the net profit before and after tax by the sales and multiplying by 100 calculates these next two ratios. In this example the sums are 8,100/60,000 Ã 100 = 13.5 per cent and 6,723/60,000 Ã 100 = 11.21 per cent. This is a measure of how efficiently we are running the business, after taking account of financing costs and tax. The last figure shows how successful we are at creating additional money to either invest back in the business or distribute to the owner(s) as either drawings or dividends. Once again the rule here is the higher the figure the better.

Return on equity

This ratio is usually expressed as a percentage in the way we might think of the return on any personal financial investment. Taking the owners' viewpoint, their concern is with the profit earned for them relative to the amount of funds they have invested in the business. The relevant profit here is after interest and tax (and any preference dividends) have been deducted. This is expressed as a percentage of the equity that comprises ordinary share capital and reserves. So in this example the sum is: return on equity = 6,723 / 18,700 Ã 100 = 36 per cent.

Return on capital employed

This takes a wider view of company performance than return on equity by expressing profit before interest, tax and dividend deductions as a percentage of the total capital employed, irrespective of whether this capital is borrowed or provided by the owners.

Capital employed is defined as share capital plus reserves plus long-term borrowings. Where, say, a bank overdraft is included in current liabilities every year and in effect becomes a source of capital, this may be regarded as part of capital employed. If the bank overdraft varies considerably from

year to year, a more reliable ratio could be calculated by averaging the start- and end-year figures. There is no one precise definition used by companies for capital employed. In this example the sum is: return on capital employed = 8,700/18,700 + 10,000 Ã 100 = 30 per cent.

Tests of liquidity

In order to survive, companies must also watch their liquidity position, by which is meant keeping enough short-term assets to pay short-term debts. Companies go out of business compulsorily when they fail to pay money due to employees, bankers or suppliers.

The liquid money tied up in day-to-day activities is known as working capital, the sum of which is arrived at by subtracting the current liabilities from the current assets. In the case of High Note we have $/£/â¬21,108 in current assets and $/£/â¬4,908 in current liabilities, so the working capital is $/£/â¬16,200.

Current ratio

As a figure the working capital doesn't tell us much. It is rather as if you knew your car had used 20 gallons of petrol but had no idea how far you had travelled. It would be more helpful to know how much larger the current assets are than the current liabilities. That would give us some idea if the funds would be available to pay bills for stock, the tax liability and any other short-term liabilities that may arise. The current ratio, which is arrived at by dividing the current assets by the current liabilities, is the measure used. For High Note this is 21,108/4,908 = 4.30. The convention is to express this as 4.30 : 1 and the aim here is to have a ratio of between 1.5 : 1 and 2 : 1. Any lower and bills can't be met easily; much higher and money is being tied up unnecessarily.

Quick ratio (acid test)

This is a belt and braces ratio used to ensure that a business has sufficient ready cash or near cash to meet all its current liabilities. Items such as stock are stripped out as although these are assets, the money involved is not immediately available to pay bills. In effect the only liquid assets a business has are cash, debtors and any short-term investment such as bank deposits or government securities. For High Note this ratio is: 12,000/4,908 = 2.44 : 1. The ratio should be greater than 1 : 1 for a business to be sufficiently liquid.

Average collection period

We can see that High Note's current ratio is high, which is an indication that some elements of working capital are being used inefficiently. The business has $/£/â¬12,000 owed by customers on sales of $/£/â¬60,000 over a six-month period. The average period it takes High Note to collect money owed is calculated by dividing the sales made on credit by the money owed (debtors)

and multiplying it by the time period, in days; in this case the sum is as follows: 12,000/60,000 Ã 182.5 = 36.5 days.

If the credit terms are cash with order or seven days, then something is going seriously wrong. If it is net 30 days then it is probably about right. In this example it has been assumed that all the sales were made on credit.

Average payment period

This ratio shows how long a company is taking on average to pay its suppliers. The calculation is as for average collection period, but substituting creditors for debtors and purchase for sales.

Days stock held

High Note is carrying $/£/â¬9,108 stock of sheet music, CDs etc and over the period it sold $/£/â¬30,000 of stock at cost (the cost of sales is $/£/â¬30,000 to support $/£/â¬60,000 of invoiced sales as the mark-up in this case is 100 per cent). Using a similar sum as with average collection period we can calculate that the stock being held is sufficient to support 55.41 days sales (9,108/10,000 à 182.5). If High Note's suppliers can make weekly deliveries then this is almost certainly too high a stock figure to hold. Cutting stock back from nearly eight weeks (55.41 days) to one week (seven days) would trim 48.41 days or $/£/â¬7,957.38 worth of stock out of working capital. This in turn would bring the current ratio down to 2.68 : 1.

Circulation of working capital

This is a measure used to evaluate the overall efficiency with which working capital is being used. That is the sales divided by the working capital (current assets â current liabilities). In this example that sum is: 60,000/16,420 = 3.65 times. In other words, we are turning over the working capital more than three and a half times each year. There are no hard and fast rules as to what is an acceptable ratio. Clearly the more times working capital is turned over, stock sold for example, the more chance a business has to make a profit on that activity.

Tests of solvency

These measures see how a company is managing its long-term liabilities. There are two principal ratios used here.

Leverage/gearing

This measures as a percentage the proportion of all borrowing, including long-term loans and bank overdrafts, to the total of shareholders' funds â share capital and all reserves. The gearing ratio is sometimes also known as the debt/equity ratio. For High Note this is: (4,908 + 10,000) / 18,800 = 14,908/18,800 = 0.79 : 1. In other words, for every $/£/â¬1 the shareholders

have invested in High Note they have borrowed a further 79p. This ratio is usually not expected to exceed 1 : 1 for long periods.

Interest cover

This is a measure of the proportion of profit taken up by interest payments and can be found by dividing the annual interest payment into the annual profit before interest, tax and dividend payments. The greater the number, the less vulnerable the company will be to any setback in profits, or rise in interest rates on variable loans. The smaller the number, the more risk that level of borrowing represents to the company. A figure of between 2 and 5 times would be considered acceptable.

Tests of growth

These are arrived at by comparing one year with another, usually for elements of the profit and loss account such as sales and profit. So, for example, if next year High Note achieved sales of $/£/â¬100,000 and operating profits of $/£/â¬16,000 the growth ratios would be 67 per cent, that is, $/£/â¬40,000 of extra sales as a proportion of the first year's sales of $/£/â¬60,000; and 84 per cent, that is, $/£/â¬7,300 of extra operating profit as a percentage of the first year's operating profit of $/£/â¬8,700.

Some additional information can be gleaned from these two ratios. In this example we can see that profits are growing faster than sales, which indicates a healthier trend than if the situation were reversed.

Market tests

This is the name given to stock market measures of performance. Four key ratios here are:

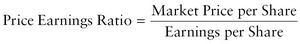

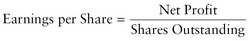

The after-tax profit made by a company divided by the number of ordinary shares it has issued.