Teutonic Knights (25 page)

Authors: William Urban

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Medieval, #Germany, #Baltic States

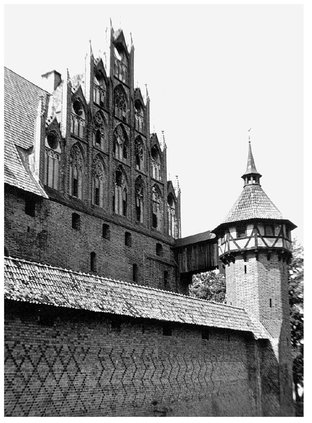

Marienburg castle walls and warehouse facade, showing the covered walkways that protected the garrison from rain and hostile arrows.

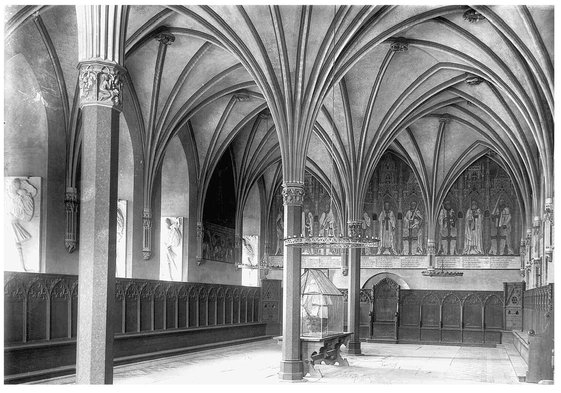

The great hall in Marienburg castle. Unfortunately, the nineteenth-century restorers told us more about their artistic tastes than about the medieval era. Still, the elegant vaulting of the ceiling remains impressive even after the restorations following World War II.

Marienburg castle’s middle courtyard, as reconstructed after World War II. Every comfort was provided for the garrison and visitors so that they did not suffer from the long cold and wet winters.

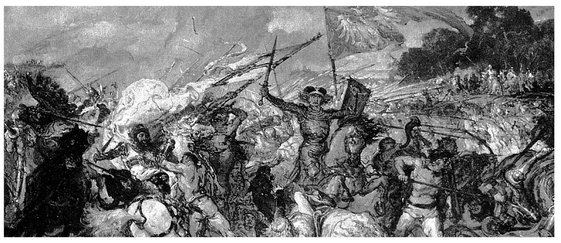

Jan Matejko’s sketch for his large scale painting of the Battle of Tannenburg (1878). Vytautas holds the viewers attention, while Jagiełło watches from a distant rise. In the left foreground Grandmaster Ulrich von Jungingen falls.

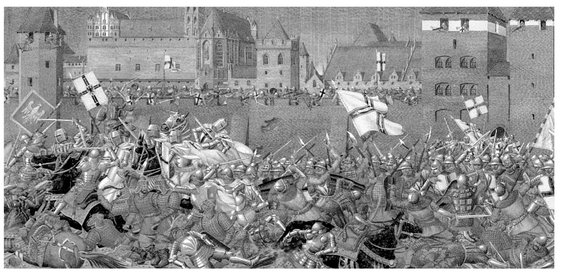

Werner Peiner: The Siege of Marienburg (1939). In this battle between the Teutonic Knights and the Poles beneath Marienburg castle, the Teutonic Knights are obviously winning; in reality, the Poles simply marched away.

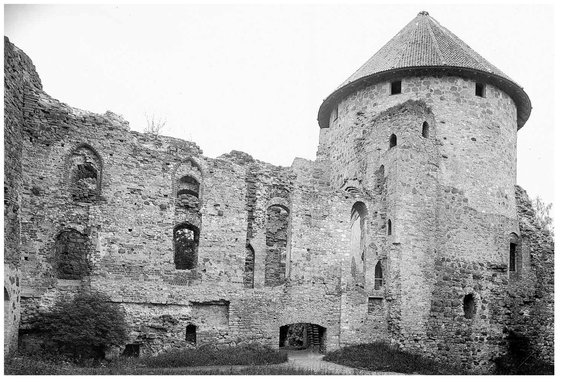

The ruins of the great castle at Wenden, where the Livonian master usually resided. This was destroyed in the Livonian War by Ivan the Terrible.

Banners hanging inside Marienburg castle. The battle flags captured at Tannenburg were taken to Cracow and put on public display. These are faithful copies.

The Lithuanian Challenge

In the mid-thirteenth century Teutonic Knights had brought about the conversion of a deadly enemy, Mindaugas, and crowned him as the first king of Lithuania. They did this in the traditional manner for the region, by persuading him that it was to his advantage to have the crusaders as allies rather than as enemies. With help from the Teutonic Knights – or, more to the point, perhaps, without the Teutonic Knights striking into his territories from the north and west – Mindaugas could expand his realm into Tatar-threatened Rus’ian lands in a wide arc from his north-east to his south-west.

For Mindaugas, the only unpleasant aspect to the reversal of religious orientation – other than having to explain his change of heart to his priests and boyars – was to have a few drops of water sprinkled on his head and having to listen to an occasional strange ritual with exotic music. Being already monogamous and not much impressed by any religious doctrine, pagan or Christian, he changed his behaviour and attitudes very little. This scepticism was not a good sign for the Teutonic Knights – conversions based solely on

Realpolitik

are rooted in sandy soil, and in the early 1260s Mindaugas began to see more disadvantages in being a Christian than advantages. Consequently he returned to paganism with about as much enthusiasm as he had embraced Catholicism – it seemed the best way to placate those nobles who admired the way the Samogitian pagans were crushing crusader armies. The change of heart saved Mindaugas only a short while, however, his enemies assassinating him anyway, but his rejection of Roman Catholicism altered the seemingly predetermined history of the Baltic region. His successors were to remain pagan for more than a century, largely because their important subjects believed that the native gods brought victories in battle, but also because their Rus’ian subjects were more willing to tolerate pagans ruling over them temporarily than to accept Roman Catholic help. Gediminas (b.1257, grand prince 1316 – 41) was an eminently practical ruler, and so were his many descendants; perhaps nowhere else in Europe did a dynasty exist which operated more consistently by the rules of self-interest than did these talented and resourceful men. They were not about to put their Rus’ian policies at risk by conversion to Roman Catholicism, but they were quite willing to allow Western Christians to believe what they wanted – that only the Teutonic Order’s aggressions stood between them and salvation.

The Lithuanian rulers were called grand princes, a term familiar to their Rus’ian subjects. But the theoretical title meant little. Most followers and retainers gave their loyalty to the Gediminid dynasty on the basis of family ties and the assurance of offices and rewards, not on the basis of ancient tradition or religion. Many Lithuanian nobles had undergone Orthodox baptism in order to placate the Rus’ians in the towns where they had been stationed as rulers and garrison commanders; many had married Christian women, Orthodox and Catholic alike. But others remained pagan. Without any doubt, paganism had some strong attractions, not the least of which was its assurance that Lithuania would continue to be ruled by a Lithuanian. Also, the adherence to paganism was the only way to guarantee that the independent-minded Samogitians would recognise a ruler from the central hill country of Lithuania – they would reject a weak Christian ruler as assuredly as they had rejected the powerful Mindaugas. Paganism was not a dying religion in Samogitia. To the contrary, it was held with all the fervour of uneducated and untravelled fundamentalists of any religion today.

When the pagans had returned to power they had burned the cathedral in Vilnius, covered its ruins with sand, and erected a shrine to Perkunas over it. This shrine to the thunder god probably had the same dramatic impact on the pagans as the Christian cathedral it replaced had made earlier. Traditionally, pagans conducted their ceremonies in the sacred forests, which perhaps explains why this masonry structure was left open to the sky with twelve steps leading up to a huge altar. There the priests may have placed a wooden statue of the god and maintained an eternal flame. This suggests an evolving paganism, a dynamic religion which adopted some of the more popular features of its competition.

The Gediminid princes prided themselves on being secular and tolerant for their day. They were superstitious, but they had no desire to force their paganism on others, or even to offer it to them. The grand princes allowed Franciscan friars to maintain a chapel in Vilnius for Roman Catholic merchants and emissaries, only once turning them into martyrs. Even more toleration was granted Orthodox churchmen – for the practical reason that many of their subjects were Orthodox. Some of their Tatar bodyguards were Moslems who lived in their own protected communities. The princes, therefore, followed a policy of nominal paganism that guaranteed extensive toleration of group traditions. This survived as late as World War Two in eastern and east central Europe, with governments negotiating with the leaders of minority groups who then enforced the laws and edicts issued from above.

This practicality should never mislead us into thinking that medieval group toleration is the same as modern tolerance for individual choices, or even that it is the same as Moslem toleration, which is too often only permission to live as second-class citizens. It was generous for its time, and that is surely praise enough.

Division in the crusader ranks brought an end to the string of successes that had marked the end of the thirteenth century. Once the Prussian master had control of the wilderness marking the frontiers with Lithuania and Masovia, once the Livonian master had conquered the Semgallians, each reverted to a defensive strategy. These were responses to local conditions: Poland was reuniting, Riga and the archbishop of Riga were becoming restive, and the papacy was in turmoil following the kidnapping of Boniface VIII and the transfer of the curia to Avignon. The Holy Roman Empire was insufficiently stable for the grand master to be able to establish the kind of close personal relationship that had existed with Ottokar of Bohemia. Intelligent powerful dukes and archbishops stayed at home to await the outcome of events.

As a result, the Teutonic Knights were unable to bring together the coalitions that had made victory possible only a few years before. The Rigans and the archbishop were now enemies, and the German nobles in Livonia as well as the native tribes were concerned about the civil war there. Crusaders from Germany and Poland had not come to Prussia for years. The Masovian and Galician-Volhynian dukes who had shared the rigours of the Sudovian campaign were not interested in fighting north of the Nemunas (Memel) River. As a result of all these developments, the Teutonic Knights were unable to make the show of force in the Samogitian wilderness that was necessary to suppress the pagans there who were supporting rebellions in Prussia and Livonia.

The Samogitians eventually threw in their lot with Duke Vytenis (1295 – 1316). (They did so literally, since no decision was ever reached without a priest casting lots to ask advice from the gods.) Vytenis had been rampaging through Livonia. Now the united pagan armies struck the Christianised natives in Semgallia, Kurland, and Samland, and the leaders of the Teutonic Knights could do little to stop them. The problem became so serious that after 1300 every grand master had come north to investigate. Each had concluded that the problem was not military, but political. The solution was to remove the archbishop of Riga and his citizens from the enemy coalition. Knowing that this could be done better from Avignon than Marienburg, the grand masters had returned repeatedly to the Holy Roman Empire to confer with the leading political and ecclesiastical figures.

Meanwhile, patrols guarded the Prussian frontier against incursions, and minor raids across the wilderness kept some pagans at home to guard their villages and fields. The main base for Prussian patrols was at Ragnit, on the left bank of the Nemunas about sixty miles from the river’s mouth and almost equidistant from Königsberg on the Pregel River and the castle at Memel, guarding the mouth of the Kurland bay and the coastal road to Livonia. Those three points formed a rough triangle defining the Christian presence in the river valley. Supported by another strong castle just downriver at Tilsit, the garrison at Ragnit had borne the brunt of the border war. For attacks across the wilderness, the castellan at Ragnit called on the advocates of Samland and Nattangia and their native militias. The method of warfare was to steal cattle, burn homes and crops, and kidnap everyone who did not hide or die in resisting capture. By the standards of the time this was not immoral. Instead, in an era when fortifications were almost impregnable and troops had to be paid in booty, wearing down the enemy was the only practical strategy. Moreover, the crusaders justified whatever brutal acts they and their subjects committed as necessary to achieve a worthy goal, the end of raids on Christian lands and the extirpation of paganism.

Similar patrols watched the paths along Livonia’s southern and eastern frontiers from bases at Goldingen, Mitau, Dünaburg, Rositten, Marienhausen, and Neuhausen. The Livonian master had resettled the Semgallians to the north, around Mitau. Their lands reverted to forest and swamp, a desolate region patrolled by experienced and ruthless scouts from both sides. No one else entered the region. For the Livonian master to communicate with Prussia in the wintertime, he had to send riders across Kurland, then down the coast to Memel. Handing a message to one of the many captains who sailed from Livonian ports was risky because Riga was in revolt at this time, and merchants tended to stick together; in any case, the seas were only open in the summer.

Preachers of the crusades over the years had told Christians that the enemies of the cross were foes of both God and man. Therefore, pagans, Saracens, schismatics, and heretics had no right to exist. They were a danger to Christendom and had to be destroyed, like sheep when infected with disease, to save the healthy ones. Whatever doubts may have existed were quickly stilled by the Church. Churchmen declared that any war between Christians and infidels was a just war, a proper means of protecting and expanding Christendom. Citing St Augustine, they declared that the entire life of pagans was sinful, regardless of the goodness or evil of their actions, because everything they did was done without knowledge of the eternal truths of God. To be sure, pagans should not be forced to accept Christianity. They were to be permitted to survive, like the Jews, in hope that they or their descendants might eventually be converted and saved. In the meantime, pagans should not be permitted any role in society that might cause Christians to admire them. Therefore Christians should strip them of property and power, of pride and prestige. From this it followed that the Samogitian pagans had no right to an independent state, especially not one in which they persecuted Christians and hindered missionary activity. It was on the basis of that argument that the Emperor Frederick II had issued the Golden Bull of Rimini in 1226, giving Prussia and other pagan territories to the Teutonic Knights, and that Pope Alexander IV (1254 – 61) had awarded them everything they could conquer. Moreover, since pagans were dangerous enemies of Christendom, often raiding Poland, Prussia, and Livonia, popes had authorised a perpetual crusade and emperors had urged nobles and knights to take the cross against them. It was the pious duty of Christians everywhere to assist in the defeat of dangerous heathens. The Dominican friars, preachers of every crusade and members of the most prestigious order of the time, assured potential volunteers that once crusaders had cut down the enemies of God, then Christ himself would hurl their souls into hellfire.

24

Still, it was easier to preach the crusade and recruit crusaders than it was to reach the Samogitians to kill them. The Samogitian branch of the Lithuanian people had immigrated into the lowlands north of the Nemunas River from the east and had not quite reached the coast. They lived in the valleys of the well-drained interior hill country, avoiding the mosquito-filled swamps and dense forests that formed a natural wilderness around them. This wilderness was almost untouched by humans, thanks to religious beliefs which incorporated forest gods and spirits into a wider pantheon, and thanks also to fear of attack from dangerous neighbours, which caused them to hew down giant trees across possible paths. This wilderness grew more dense after the arrival of the crusaders. Small raiding parties, often composed of native peoples who had suffered Lithuanian attacks for generations, annihilated isolated farmsteads, leaving few surviving settlements whose people could report incursions by larger parties of knights and native warriors; and the Samogitians, unlike the Lithuanians in the central highlands, lacked an effective system of taxation or military service that would support isolated castles as bases for scouts. Within a few years the western Samogitian communities vulnerable to attack from Memel and Kurland were abandoned and the tribesmen established new villages further inland. The unused fields soon became part of the forest. In time a vast wilderness up to ninety miles wide stretched along every frontier separating the Christian domains in Prussia and Livonia from Samogitia and Lithuania. Only a few paths led through it.