Teutonic Knights (24 page)

Authors: William Urban

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Medieval, #Germany, #Baltic States

Prussia was easy to reach by either land or sea, but it lay at sufficient distance to escape the turmoil of Western political struggles. Neither the Hundred Years’ War, the vicissitudes of the empire, the advance of the Turks, nor the troubles of the papacy disturbed it. It was an island of peace with a war on one coast (Samogitia), and it was winning that war with the help of the constant stream of crusaders from the West.

No longer was this just a German crusade, as it had been after the mid-thirteenth century when armies of Polish knights ceased to participate. Many Englishmen came, as did an Orsini duke from Naples and numerous French princes. Although the kings of Poland abstained, Poles from Silesia and Masovia came, as did Bohemians, some Hungarians, and a few Scots. It was indeed an international crusade.

The ceremony of knighthood lay near the heart of this crusading ardour. Each expedition into Samogitian forests and swamps was an opportunity for poor squires to win their spurs honourably and cheaply, and for rich nobles to earn respect by lavish hospitality and courage. The Austrian poet Peter von Suchenwirt described one expedition to seek knighthood in 1377. He concluded his narrative with this exhortation: ‘One counsel I give to noble folk: he who will become a good knight, let him take as companion Lady Honour and St George. “Better knight than squire!” Let him bear that word in his heart, with will and with good deeds; so shall he defy slander, and his name shall be spoken with honour.’

Many squires took that admonition to heart. So did experienced campaigners. Prussia became a major showplace for fourteenth-century chivalry, visited by knights from Scotland, England, France, and Italy, men who had seen every monarch and tournament champion. Such knights came back for a second, third, and fourth crusade.

Polish assertions that the Teutonic Order was evil in its intents, practices, and theology eventually lost credibility with mainstream churchmen and the Western public by the mid-1350s. Partly this was due to the hyperbole of the era, in which the slightest fault would be magnified into a chasm. But more importantly, it ran against the experience of eyewitnesses. Knights and prelates who had been in Prussia and Samogitia, who had seen holy war first-hand, who had met clerics and nobles while travelling across Germany and Poland, were able to make judgements for themselves. Their verdict was almost unanimously in favour of the crusaders.

The situation would be different in the 1400s. First of all, the crusade was effectively suspended from the 1390s on. Lithuania had been converted to Christianity and tied closely to the Polish state; and Samogitia was occupied by the Teutonic Order. Secondly, the advance of the Turks into the Balkans diverted crusading energies in that direction; that was a field in which Polish participation was potentially important. Thirdly, the balance of power was slowly shifting, and Poland, despite finding it hard to believe that the long nightmare of disunity and weakness was at an end, emerged from the battle of Tannenberg (1410) as the dominant power of the region. Public opinion always respects power.

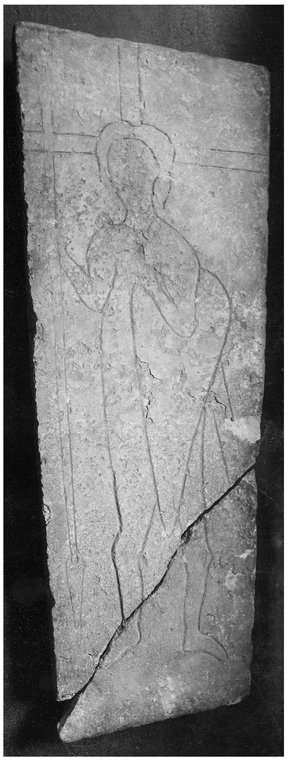

Grave marker at Holm, one of the first two churches in Livonia, showing a thirteenth-century warrior with a kite-shaped shield.

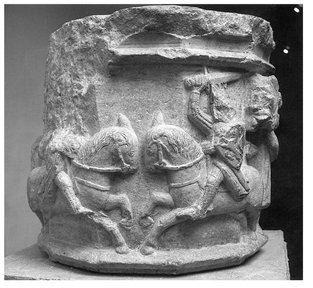

Charging German knights on an early thirteenth-century metal casket from the Cathedral Treasury, Aachen, Germany. All German kings were crowned in this church, after which they would proceed to their election as Holy Roman Emperor and the coronation.

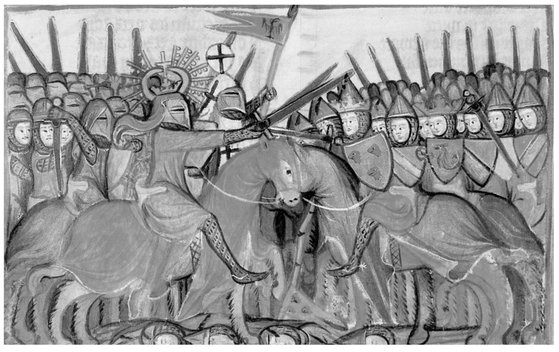

A manuscript illustration of crusaders in combat against eastern warriors. The helmet of the commander later reappears in the movie Alexander Nevsky, but it should be noted that he does not wear the order’s cloak. Also, the Russian troops bear coats of arms, which was not yet common for them.

Jousting knights. Note the pot helmets and the musicians. A fourteenth-century frieze in Marienburg castle in Prussia.

Knights in combat from a capital in Marienburg castle. The coat of arms indicates that this is a secular knight. The lion rampant is a common devise, but many crusaders came from Meissen and Flanders, where this was used. Interestingly, Teutonic Knights did not joust – too secular and vainglorious.

Knights in combat, from a capital in Marienburg castle.

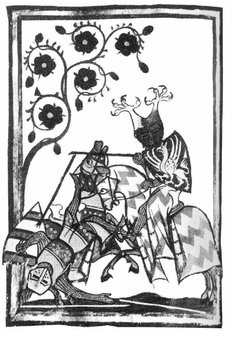

Knights jousting, victory going to the rider with the griffon coat of arms, a common motif.

Chansonnier Manesse

, from the fourteenth-century Manesse Liederhandschrift, Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg.

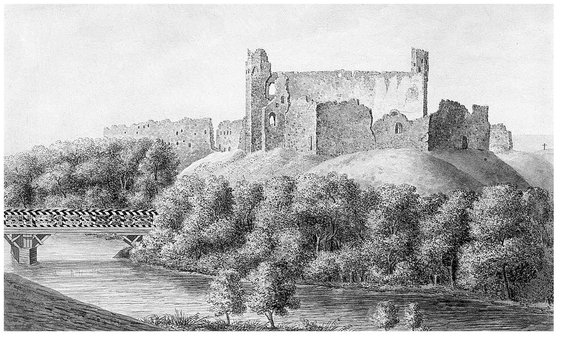

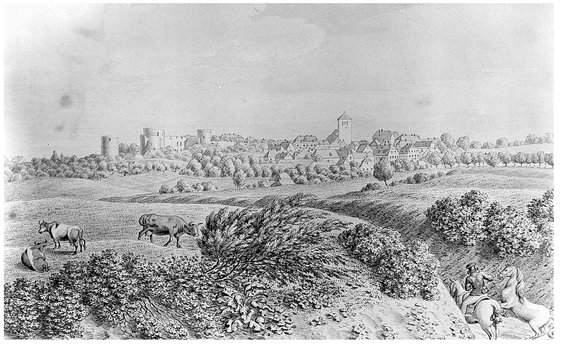

Romantic drawing of the ruins of Doblen, a major castle in Kurland that protected the communications route to Prussia. Like most castles it was constructed on a natural rise where water obstacles increased attackers’ difficulties in achieving surprise or prosecuting a siege.

Romantic drawing of the ruins of Wenden, the seat of the Livonian master in the Livonian Aa River valley.

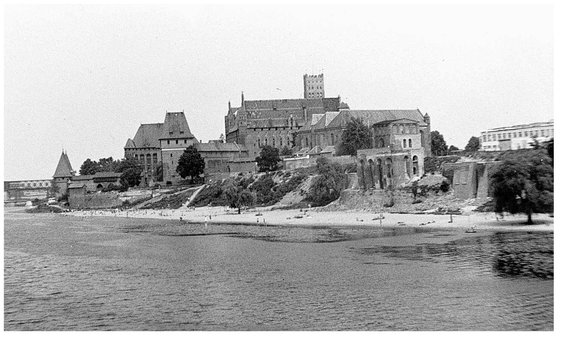

Marienburg castle from the Nogat River, with the water gate at the left, then the grand master’s residence, and finally the high castle with the Priests’ Tower in the center of the fortress. There was little chance for a successful assault on the walls from the narrow beach, and generally the Teutonic Order’s allies (Danzig and other commercial centers) guaranteed naval superiority.

Marienburg castle from the southeast. Successive lines of defense sheltered the high castle from attack, while the high tower provided the defending commander with a good view of enemy activity.