Tender at the Bone (42 page)

Read Tender at the Bone Online

Authors: Ruth Reichl

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Cooking, #General

Cecilia seemed neither surprised nor offended. “No,” she said. “After I walked out of China I could never have gone back to the old life. It was like coming to another world. I feel sorry for the women I grew up with who did not have a chance to discover that they could take care of themselves.”

Marion nodded.

“And you?” Cecilia asked. “Your children missed you when you were working with James. Do you ever regret going?”

Marion shook her head. “No,” she said firmly. “My family may not have liked it, but I think I finally became the person I was meant to be.”

Cecilia held up a platter of entirely white food. “Very Chinese,” she said, pointing out that the chicken breast was cut into batons precisely the same size as the neatly trimmed bean sprouts. As she served, she mused, “Sometimes I come into the restaurant late at night when nobody is here. And I look at the floor and think that it hasn’t been scrubbed right. I just get down on my knees and do it myself; it is a good feeling. My mother could not have done that.”

The chicken was so tender it evaporated in my mouth and the bean sprouts seemed to be all juice. Cecilia held one up. “Must trim them completely,” she said. “Most Chinese restaurants serve them with the threads still attached. Nobody wants to do the work anymore.”

Afterward there was sea-turtle soup, the meat like velvet hugging bones as smooth as stones. “Sea turtles are very hard to find in San Francisco,” said Cecilia. She gave a small, satisfied smile. “But you can get anything if you try hard enough.”

“Is this the last course?” asked Marion. I fervently hoped not; I was no longer hungry, but I was not ready to face the bridge.

“Just a few olives and a little melon,” said Cecilia. “I told you it was a small lunch.” She held out a plate with large, smooth olives, unlike any I had seen. “Chinese olives,” said Cecilia proudly.

I bit into one. “Lawrence Durrell,” I said, wondering if I was pronouncing the name right, “said that olives had a taste as old as cold water.” I rolled the musty pit around in my mouth, thinking that if I could come up with just one description as good I could call myself a writer.

“As old as cold water,” said Marion thoughtfully. “That’s just right, isn’t it?” She looked at me with admiration, as if knowing the phrase was an accomplishment.

The waiter brought the melon, followed by a crystal decanter filled with aged cognac. Cecilia filled three snifters.

“You know I won’t drink that,” said Marion.

“It will be like China,” said Cecilia. “I will drink for you.”

Marion smiled and turned to me. “Everywhere we went in China they toasted us with cognac. Alice was pregnant and could not drink so Cecilia had to drink for all three of us.”

“We could not lose face by refusing,” explained Cecilia.

“One night,” said Marion, “she drank thirty-two shots of cognac and did not get drunk. I will never know how she did it.”

“It is easy,” said Cecilia. “You just make up your mind not to let

it affect you. And then it doesn’t.

Gambei!”

She raised her glass and downed the liquor.

I didn’t really want the cognac, but I didn’t know how to say so. I did not want to lose face.

“Gambei!”

I said and raised my glass.

And then it hit me that I really didn’t want to drink it and I didn’t have to. I put the glass down and shook my head. “I have to drive,” I said. Cecilia gave me a look I could not fathom. I will never know if it was respect or disappointment. And then we thanked her and walked to the car.

I climbed in, shut the door, put the key in the ignition, and for a moment all the fear came back.

And then I turned the key and the motor turned over. I pulled out into the traffic and approached the Embarcadero Freeway. As I sailed up the ramp and took the first curve I looked at the bridge, glittering in front of me. It was beautiful.

Then I was on the bridge and the sun was shining and Marion was talking about the meal we had just eaten. The old, cold taste of olives filled my mouth once again. “You know,” said Marion, “Chinese women do not leave their husbands. Cecilia has done everything by the strength of her will. Isn’t she amazing?”

“What did it feel like to be an alcoholic?” I asked.

Marion considered for a minute. “As if there was not enough gin in the world,” she said finally.

“You’re amazing too,” I said.

Marion waved her long hands as if she were pushing the thought from her. “Oh, hon,” she said. “Nobody knows why some of us get better and others don’t.”

I thought of my mother. And then, suddenly, she seemed very far away. The bridge was strong. Doug was waiting on the other side. I was not afraid. If I wanted, I could just keep driving.

I stepped on the gas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Everybody I have ever known has helped me write this book. But, for their practical help and advice, I want to thank:

Everybody I have ever known has helped me write this book. But, for their practical help and advice, I want to thank:

Paula Landesman and Jerry Berger, who were endlessly encouraging.

Frank Assumma and Karen Kaczmar, who gave me a room of my own in the country.

Ann Vivian and Andy Dintenfass, for the cottage in the Vineyard.

My agent, Kathy Robbins, who put the proposal on a table and walked around it, worrying.

Betsy Feichtmeir, who tested the recipes for the sheer fun of it.

And my editor, Ann Godoff, who kept saying, “Keep going.”

QUESTIONS AND TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION

1. The first two chapters of

Tender at the Bone

feature the culinary shortcomings of Ruth Reichl’s relatives, particularly her mother. To what do you attribute prowess in the kitchen? Is the ability (or inability) to cook a reflection of other traits? Who are the most notorious cooks in your family?

2. Besides a perfect recipe for wiener schnitzel, what other gifts did Mrs. Peavey impart to Reichl?

3. How was Reichl affected by her three years at boarding school in Montreal? What, do you think, was her mother’s true motivation in enrolling her there?

4. In the absence of parents, what role did cooking take while Reichl was a teenager? Why did feeding her friends become her primary joy? Does

chapter 5

, “Devil’s Food,” express unique or universal notions about adolescence and self-image?

5. In what way does the topic of mental illness shape the memoir overall, particularly the bipolar disorder that afflicted Reichl’s mother? What do the book’s images evoke regarding the psychology of indulgence and hunger?

6. How does the tenderness mentioned in the title manifest itself throughout the book? How do Reichl’s sense of humor and her wry honesty play off each other?

7. What were Reichl’s early impressions of France, including her summer on the Île d’Oléron? How did her casual immersions in French cooking shape her attitudes toward cuisine in general? How did they help her on the job at L’Escargot and when she later embarked on the vineyard tour?

8. At the end of

chapter 7

, Serafina writes, “I hope you find your Africa,” in a note to Reichl. How was Reichl’s view of humanity being transformed by Serafina and Mac?

9. Did traveling in North Africa bring Reichl closer to or farther from a sense of fulfillment? How did this travel experience compare with her previous ones?

10. As Reichl watched Doug bond with her parents (he even elicited previously unknown details about her father’s life), she felt a new level of exasperation with her family. What models for marriage did she have? Was winter in Europe, with Milton often at the helm, a good antidote?

11. Reichl writes that in 1971 lower Manhattan was a cook’s paradise. What did life on the Lower East Side, from the gefilte fish episode to Mr. Bergamini’s veal breast recommendation, teach Reichl about how she would define a successful meal? Why was the Superstar so insistent that great cooking was a sure way to seduce a man? With Mr. Izzy T as navigator, what did the Superstar and Reichl both learn about themselves?

12. How does the idealism of Channing Way compare with the organic food movement of today? Have any of Nick’s tenets become part of mainstream life in the twenty-first century?

13. The now-legendary Swallow Collective was as innovative in its management style as in its menus. What chapters in culinary history are captured in Reichl’s recollections of working there?

14.

Tender at the Bone

ends with an image of Reichl conquering her bridge phobia while accompanied by Marion Cunningham, who says, “Nobody knows why some of us get better and others don’t.” What ingredients in Reichl’s life may have helped her “get better” and achieve such tremendous success in the years that would follow this scene?

15. Food writing presents the unusual challenge of conveying distinct, intangible flavors through mere words. How would you characterize Reichl’s approach to the task? Does she approach haute cuisine and comfort food in the same way? How would you have responded to her mother’s comment that by developing a career as a food writer Reichl was “wasting her life”?

16. How would you characterize the recipes Reichl selected for

Tender at the Bone?

Do they possess a common “personality”? What recipes represent the most significant turning points in your life?

A Thousand Words

It’s hard to remember a time when food memoirs were not part of the general landscape, but when I was writing

Tender at the Bone

, the genre did not exist. As I was trying to think about telling my story through food, it occurred to me that the recipes could function the way photographs did in other people’s books. I wanted readers to get to know the characters through the food they cooked and ate, to be able to taste the time. I might not be able to include a recipe for Mom’s Everything Stew, but it seemed to me that if you made her Corned Beef Ham, you might begin to understand the way her mind worked. So I took down the big, messy folder that contained the recipes Mom had torn out of magazines, the handwritten file cards that Alice once gave me, and the scraps of paper on which my own favorite recipes were scrawled and discovered that each one was an instant passport to the past.

Over time I’ve heard from many readers who have cooked the recipes, and they’ve all said how much these dishes have enhanced their enjoyment of the book. But almost all of them have added, “I wish there were photographs as well.”

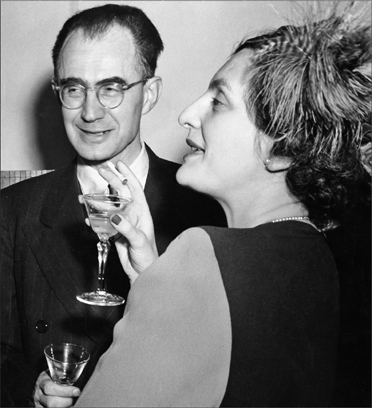

That sent me to a shelf filled with a motley collection of photo albums. I bought most of them at thrift stores, and their covers are torn, the pages so loose that each time I pick one up photos go tumbling to the floor. The pictures have been thrown in at random, so I’ll often find people who never met each other staring out from the same page. It always makes me happy to spend time among those I’ve loved best, and each time I go through the albums I discover something new. Here’s my mother looking glamorous, Aunt Birdie even tinier than I remember, Doug and me with a group of friends looking into the camera as if our whole lives are still ahead of us. Which, of course, they were.

This picture of my parents was taken at a cocktail party in the late forties a couple of years before I was born. Mom saved her clothes, and I remember this dress well; it was black with gray chiffon sleeves. Note the size of the martinis and the fact that the cigarette Mom is holding is unfiltered.