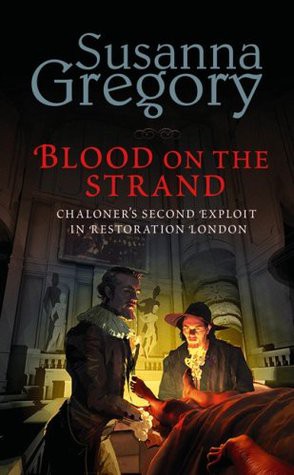

Blood on the Strand

Read Blood on the Strand Online

Authors: Susanna Gregory

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #Mystery & Detective, #General

Susanna Gregory is a pseudonym. Before she earned her PhD at the University of Cambridge and became a research Fellow at one

of the colleges, she was a police officer in Yorkshire. She has written a number of non-fiction books, including ones on castles,

cathedrals, historic houses and world travel.

She and her husband live in Carmarthen.

Visit the author’s website at:

www.susannagregory.co.uk

The Matthew Bartholomew Series

A Plague on Both Your Houses

An Unholy Alliance

A Bone of Contention

A Deadly Brew

A Wicked Deed

A Masterly Murder

An Order for Death

A Summer of Discontent

A Killer in Winter

The Hand of Justice

The Mark of a Murderer

The Tarnished Chalice

To Kill or Cure

The Thomas Chaloner Series

A Conspiracy of Violence

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 978-0-748-12453-4

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2007 Susanna Gregory

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

For Michael Churgin

London, early May 1663

Matthew Webb was cold, wet and angry. The rain, which had started as an unpleasant, misty drizzle, was now the kind of drenching

downpour that was likely to last all night. Fuming, he adjusted his hat in the hope of stopping water from seeping down the

back of his neck, but the material was sodden, and fiddling only made matters worse. Cheapside was pitch dark at that late

hour, and he could not see where he was putting his feet, so it was only a matter of time before he stepped in a deep puddle

that shot a foul-smelling sludge up the back of his legs. He ground his teeth in impotent rage, and when the bells of St Mary-le-Bow

chimed midnight, he felt like smashing them.

It was a long walk from African House on Throgmorton Street to his handsome residence on The Strand, and he should have been

relaxing in the luxury of his personal carriage, not stumbling along the city’s potholed, rain-swept streets like a beggar.

He cursed his wife for her abrupt announcement that she had had

enough of the riotous Guinea Company dinner and was going home early. And how dare she forget to send the vehicle back for

him once it had delivered

her

safe and dry to Webb Hall!

It was not just a thoughtless spouse who had earned his animosity that night, either. There were also his Guinea Company colleagues,

who had seen his predicament but failed to come to his rescue. It was true they were drunk, because it had been a long evening

and the Company was famously lavish with wine at its feasts, but when everyone had spilled noisily out of African House at

the end of the dinner, it had been obvious that Webb was the only one whose coachman was not there to collect him. Surely,

one

of his fellow merchants could have offered to help? But no – they had selfishly packed themselves inside their grand transports

and rattled away without so much as a backwards glance.

Webb had certainly expected Sir Richard Temple to step in and save him. The seating arrangements that evening had placed them

next to each other, and they had talked for hours. Cannily, Webb had used the opportunity to do business – he owned a ship

that brought sugar from Barbados and Temple was thinking of purchasing a sugar plantation with money from the rich widow he

intended to marry. It was obvious they could benefit each other, and Webb was always pleased to be of service to the gentry.

Of course, the agreement they had reached – and signed and sealed – would see Temple all but destitute in the long run, but

that was the nature of competitive commerce. It was hardly Webb’s fault that Temple had not noticed the devious caveat in

the contract before putting pen to paper.

The merchant’s ugly, coarse-featured face creased into

a scowl as he recalled the reactions of some Company members when he and Temple had announced their alliance. The loud-mouthed

Surgeon Wiseman had declared that

he

would have nothing to do with men involved in the heinous industry that used slave labour, and several others had bellowed

their agreement. Wiseman’s medical colleague Thomas Lisle was among them, which was a blow, because Lisle was popular and

reasonable, and men tended to listen to him.

Not everyone had taken the surgeons’ side, though: some had the sense to see that sugar was needed in London, that the plantations

required a workforce, and that slaves were the cheapest way to provide it. The wealthy Brandenburger, Johan Behn, had attempted

to explain the economics of the situation, but most members were too drunk to understand his complex analysis, and had cheered

when Wiseman, in his arrogant, dogmatic manner, had declared Behn a mean-spirited bore.

Then Temple had stood and raised his hand for silence. If people wanted affordable sugar, he had said crisply, they would

have to put squeamish sentiments aside. Even Wiseman could think of no argument to refute

that

basic truth. Unfortunately, a foppish, debauched courtier called Sir Alan Brodrick had spoiled the victory by ‘accidentally’

hitting Temple over the head with a candlestick. Debates at Guinea Company gatherings often ended in violent spats – or even

duels – and members were used to a little blood. Their guests were not, however, and Webb recalled the shock on the Earl of

Bristol’s face at the way the disagreement had been resolved.

Webb turned into Paternoster Row, swearing viciously as wind blew a soggy veil of rain straight into his eyes. A cat hissed

at him as he passed, and in the distance he

could hear the cries of bellmen, announcing that all was well. Webb grimaced. All was

not

well. He had never met the Earl of Bristol before, and he had been delighted when the man had accepted the Company’s invitation

to its annual dinner. Being low-born – Webb had started life as a ditcher – it was not easy to break into the exclusive circles

of the privileged, not even for those who had become extremely rich. However, Bristol, who had no money of his own, had a

reputation for socialising with anyone he thought might lend him some. Webb had cash to spare, and saw the impecunious earl

as his route to the respectability and acceptance he craved. He had intended to befriend Bristol that night, and the acquaintance

would open doors that had hitherto been closed to him.

Webb had spent an hour hovering at the edge of the bright throng that surrounded Bristol, waiting for an opportunity to make

his move. Unfortunately, he had made the mistake of taking his wife with him, and Silence Webb had heard some of the things

the witty but spiteful Bristol had said. She had found them amusing and laughed with the rest, until he had made the quip

about the decorative ‘face patches’ that were all the rage at Court. Every lady of fashion stuck one or two false moles to

her cheeks, and Silence, eager to prove herself as cultured as the rest, had managed to glue fourteen of them around her ample

visage. Because of this, Bristol’s casual remark that an excess made their wearers look like victims of the French pox had

been taken personally. Proving to the entire Guinea Company that her Puritan name had been sadly misapplied, Silence had forced

her way through the crowd and placed two meaty hands on Bristol’s table, leaning forward to glare at him.

‘I do not like you,’ she had said loudly, stilling the frivolous chatter that bubbled around the man. ‘I prefer your rival,

Lord Clarendon, because

he

is a man of taste and elegance.’

It was not every day an earl was harangued by an exditcher’s wife, and for once Bristol’s famous wit failed to provide him

with a suitably eloquent response. ‘Madam, I … ’ he had stammered.

‘You are fat, and your doublet is twenty years out of date,’ Silence had continued in a ringing voice, so her words carried

the length of the hall. People began to turn around to see what was happening. ‘And you stink of onions, like a peasant.’

‘Well, there you have it, Bristol,’ drawled the dissipated Brodrick. He was Lord Clarendon’s cousin, so always ready for a

chance to snipe at his kinsman’s deadliest enemy. ‘Clarendon

never

smells of onions, so he has the advantage of you in this dreadfully serious accusation.’

People had tittered uneasily, and Webb had taken the opportunity to haul Silence away before she could say anything else.

Bristol had not smiled, though, and Webb knew he was angry. The merchant stopped for a moment, to shake water out of his hat;

under the thin soles of his expensive shoes the road felt gritty with wet soot and ashes. Yet perhaps all was not lost. He

had already lent Bristol several hundred pounds through a broker, so they were not

exactly

strangers to each other. He would call on the Earl the following morning, to apologise for Silence’s comments, and at the

same time offer to lend him more – at a rate of interest that would be irresistible. Gold would speak louder than the insults

of imprudent wives, and Bristol was sure to overlook the matter. He and Webb would be friends yet.

Webb took a series of shortcuts – he had been born in the slums known as the Fleet Rookery, and knew the city like the back

of his hand – and emerged near Ludgate. His fine shoes rubbed his soaked feet, and he began to swear aloud, waking the beggars

who were asleep under the Fleet bridge. His knees ached, too, as they often did in wet weather – a legacy of his years in

the city’s dank runnels. He thought about Silence, and wondered whether she was angry with

him

because of Bristol’s remarks. Was that why she had failed to send the carriage back to African House to collect him?

He reached The Strand, limping heavily now, and heard the bells of St Martin-in-the-Fields announce six o’clock; they had

been wrong ever since a new-fangled chiming mechanism had been installed three months before. He heaved a sigh of relief when

he recognised mighty Somerset House and its fabulous clusters of chimneys. The newly styled ‘Webb Hall’ was next door.

Suddenly, a figure loomed out of the darkness ahead and began to stride towards him. Although he could not have said why,

Webb knew, with every fibre of his being, that the man meant him harm. With a sick, lurching fear, he glanced at the alley

that led to the river. Should he try to make a run for it? But his ruined knees ached viciously, and he knew he could not

move fast enough to escape a younger, more fleet-footed man. He fumbled for his purse.

‘Five shillings,’ he said unsteadily. ‘I do not have any more. Take it and be gone.’

The fellow did not reply. Then Webb heard a sound behind him, and whipped around to see that a second man had been hiding

in the shadows. And were there others, too? Webb screwed up his eyes, desperately

peering into the blackness, but he could not tell. There was a blur of movement, and the merchant felt a searing pain in

his chest. He dropped heavily to all fours, not knowing whether the agony in his ribs or to his jarred, swollen knees was

the greater. He was still undecided when he died.

The killer handed his rapier to his companion to hold, while he knelt to feel for a life-beat. Then a dog started to bark,

and the men quickly melted away into the darkness before the animal’s frenzied yaps raised the alarm. There was no time to

snatch Webb’s bulging purse or to investigate the fine rings clustered on his fat fingers.

The mongrel was not the only witness to the crime. A figure swathed in a heavy cloak watched the entire episode, then stood

rubbing his chin thoughtfully. There was little he could have done to prevent the murder of Matthew Webb, but that did not

mean it was going to be quietly forgotten. Someone would pay for the blood that stained The Strand.

Westminster, late May 1663

Hailstones as large as pigeons’ eggs pelted the royal procession as it trooped down King Street from the palace at White Hall,

and any semblance of dignity was lost in the ensuing scramble for shelter. Horses pranced and bucked at the sudden commotion,

and the Earl of Bristol was not the only courtier to take a tumble in the chaos when the cavalcade reached Westminster Abbey.

His retainers dashed forward to drag him upright, but not before his red, ermine-fringed cloak was irretrievably stained with

the dung and filth from the road. His bitter enemy, the Earl of Clarendon, allowed himself a small, spiteful smirk before

tossing the reins of his own mount to a waiting servant and hurrying up the steps to the abbey’s great west door. Clarendon’s

massive new periwig, made from the hair of a golden-maned Southwark prostitute, had been expensive, and he did not want it

ruined by the weather – not even when it was to gloat at the gratifying sight of his rival wallowing in muck.

A handful of flustered trumpeters did their best to

produce a regal fanfare when King Charles leapt from his saddle, but His Majesty was disgracefully late, and most of the

musicians had grown tired of waiting and had wandered off. They came running when they heard the clatter of hoofs, but too

late to do their duty. Meanwhile, it had been raining hard all morning and water had seeped inside the instruments of those

who had remained, so all that emerged was a series of strangled gurgles. One youngster had had the foresight to keep his horn

dry under his hat and proudly stepped forward to prove it, but in his eagerness, he forgot what he had been told to play,

and graced the royal ears with a lively rendition of a popular alehouse song. The King shot him a startled glance, and Thomas

Chaloner, who had been assigned ‘security duties’ for the day and was in disguise as a raker – a street-sweeper – struggled

not to laugh.

Somewhat belatedly, a bell began to chime, but an admini strative hiccup had seen the ringers provided with their barrel of

refreshing ale far too early in the day, and most were now incapable of performing the task in hand. The man who had been

assigned the largest bell hastened to make up for his colleagues’ shortcomings, and produced a deep, sepulchral toll that

was more redolent of a royal funeral than a celebration to mark the third anniversary of the King’s coronation. Yet if any

Londoner did think the monarch was dead, he shed no tears: in the three years since Charles had been restored to the throne,

his Court had earned itself a reputation for debauchery, vice and corruption, and Chaloner was not the only one to think England

might have been better off under Cromwell and his sober Parliamentarians.

Courtiers, barons and members of the Royal Household hastily followed their ruler’s example by abandoning their

steeds and scurrying inside the church to escape the battering of icy missiles from the sky. Chaloner was astounded by the

number of people who were taking part in the procession, and thought it small wonder that the King was always clamouring for

money to maintain them all. There were grooms, pages and gentlemen of the Privy Chamber, masters of hawks and buckhounds,

ladies-in-waiting, and keepers of the King’s wine cellars, jewel houses, kitchens and laundries, all combining to make a dazzling

spectacle of red, blue, gold, purple and silver.

The most glorious of all was not the King, whose taste in clothes was comparatively modest, but the ebullient Duke of Buckingham.

Buckingham was the brightest star of the dissolute Court, and one of its leaders in fashion and mischief. The man who bore

the brunt of his spiteful waggery tended to be Lord Clarendon – Chaloner’s master. The Duke was always jibing the older man

about his obesity and prim manners, and their paths seldom crossed without some insult being traded. That day, Chaloner watched

Buckingham give a fair imitation of Clarendon’s short-legged waddle up the abbey steps. The voluptuous Lady Castlemaine laughed

uproariously at the performance, but no one dared rebuke her – as the King’s current mistress, she could guffaw at whomsoever

she liked.

Behind Buckingham stamped the Earl of Bristol, swearing furiously under his breath – poor horsemanship had nothing to do

with his fall into the mud, of course; incompetent servants and the weather were to blame. He was a handsome, although portly,

man with thick brown hair and a thin moustache, like the King’s. He hurled his soiled cloak at one of his retainers, revealing

that underneath he wore an overly tight doublet with ruffs, and the kind of ‘bucket-topped’ boots that had

been popular during the civil wars. Either he could not afford fashionable clothes, or he did not care that he had donned

an outfit that would not have looked out of place thirty years before.

Next to Bristol, his face an aloof, impassive mask, was Joseph Williamson, head of the country’s secret service. Before the

Earl of Clarendon had offered him work, Chaloner had entertained hopes of being hired by Williamson. He had been a spy for

a decade – a long time in an occupation so fraught with danger – and was an accomplished intelligence officer. The only problem

was that those ten years had been in the service of Oliver Cromwell’s government, and Williamson was naturally suspicious

of agents who had been employed by the King’s enemies; the fact that Chaloner had only ever plied his skills against foreign

powers, and had certainly never spied on the King, was deemed immaterial. Williamson wanted nothing to do with him, and Chaloner

was lucky Lord Clarendon was prepared to overlook his past.

At the top of the stairs, the King offered his Queen a solicitous hand across the treacherous carpet of hailstones, although

Chaloner thought there was scant affection in the gesture. There was, however, a great deal of fondness in the arm he proffered

to Lady Castlemaine. The royal paramour wore a triumphant smirk as she strutted inside, head held high. When she had gone,

the King and Queen turned to salute the assembled masses together. The King had insisted on doing this, despite rumours that

someone might try to assassinate him that day, because he liked to think of himself as a man of the people. He had even declared

a public holiday, so work would not prevent the citizens of London from coming to see him.

The citizens were mostly elsewhere that inhospitable Friday morning, however, and the ‘crowd’ that had gathered to watch him

ride from White Hall to Westminster Abbey was pitifully small. There was a smattering of merchants representing various city

companies, along with a few Royalist fanatics who were always present at such occasions, and a gaggle of beggars who hoped

someone might throw them some coins. When the King had returned from exile three years before, London’s streets had been packed

with cheering, jubilant supporters, and Chaloner was amazed that Charles and his Court had managed to alienate the population

quite so completely within such a short period of time.

Knowing a lost cause when he saw one, the King disappeared inside the church almost before he had finished the royal

salute, but the Queen lingered. Chaloner raised his hand in greeting, because he thought a raker would probably do so, and

was surprised when she waved back. It was the second time she had smiled at him since his arrival in England a few months

earlier, and he was oddly touched.

‘There is no need to go overboard,’ snapped Adrian May, the agent with whom Chaloner had been assigned to work that day. ‘And

while you leer at the Queen, an assassin might be priming his gun.’

Chaloner resisted the urge to point out that an assassin could prime all he liked, but the King was now inside the building,

and so safe from danger. He nodded noncommittally, reluctant to quarrel.

May was a thickset man with a smooth bald head and a vast collection of wigs to cover it; Chaloner had never seen him with

the same hairpiece twice. That day he sported a cheap grey one, because he was in disguise as

an abbey verger. May not only held high rank in the government’s fledgling intelligence service, but was a Groom of the King’s

Privy Chamber, too. Combined, these made him an influential figure in the world of British espionage. Sadly, he had scant

aptitude for the business, and Chaloner disliked both him and his dangerous incompetence intensely.

Meanwhile, May disapproved of Chaloner because he had been away from England for so long that he was a virtual stranger in

the country of his birth – after the civil wars, Chaloner had completed his studies at Cambridge and Lincoln’s Inn, then had

immediately been assigned duties overseas. He had returned to England after the collapse of Cromwell’s regime, only to find

himself regarded with suspicion and distrust by almost everyone he met. And May’s suspicion and distrust were the most fervent

of all.

Pushing his antipathy towards May to the back of his mind, Chaloner began another circuit of the abbey, plying his broom as

he went. Hailstones cracked under his feet, although the storm had abated and the deluge had dwindled to a hearty drizzle.

May grabbed his arm and stopped him.

‘How many more times are you going to walk around?’ he demanded. ‘Williamson’s informant said the assassin ation attempt would

be made

during

the procession – and the procession is now over. After a few prayers, everyone will go his own separate way, and the King’s

life will be the responsibility of the palace guard again.’

‘He still has to come out, though,’ said Chaloner, too experienced to be complacent. ‘And that will be an ideal time to attack.’

‘But we have already searched for lurking killers,’ argued

May, falling into step beside him. Chaloner wished he would go away – real vergers would not keep company with rakers and

any would-be regicide with a modicum of sense would know it. ‘The streets are clear. Besides, there are a dozen threats on

His Majesty’s life each week, and few ever amount to anything. We are wasting our time.’

‘You just said an assassin might be priming his gun,’ Chaloner pointed out, unwilling to let him have it both ways.

May’s voice became mocking. ‘I suppose the great Spymaster Thurloe taught you to be ever cautious. However, a

good

agent knows which threats are real and which are hoaxes, and only a fool treats them with equal seriousness.’

Chaloner did not reply. John Thurloe, who had masterminded Cromwell’s highly efficient intelligence network,

had

taught him his skills, and his decade-long survival was testament to the fact that he had learned them well – too well to

be cavalier about matters as serious as threats to the King’s safety.

May grimaced in annoyance when Chaloner declined to discuss the matter. ‘You are not very talkative today. What is wrong with

you?’

Chaloner pointed to St Margaret’s Church, a handsome building of pale-yellow stone that stood between the abbey and Westminster

Hall. ‘See that beggar? He has been loitering in that porch for the last hour. Perhaps the threat of assassination is real

after all.’

Rain pattered in the mud as May regarded Chaloner in astonishment. The deluge had turned his wig into a mass of sodden strands

that reeked of horse, and his shoes squelched as he walked. An explosion of laughter came

from a group of palace guards, who were waiting to escort the King back to White Hall. Their leader, Colonel Holles, hastened

to silence them, afraid they would disturb the ceremonies inside the abbey. Meanwhile, May’s surprise at Chaloner’s statement

turned to disdain.

‘It has been pouring all morning and beggars shelter where they can. As I said, you must learn to distinguish between real

menaces and imagined ones, Heyden. You are a fool if you see anything sinister in that fellow’s presence.’

Tom Heyden was Chaloner’s usual alias, and only a handful of people knew his real identity – because he was kin to one of

the fifty-nine men who had signed Charles I’s death warrant, Chaloner was a name best kept from Royalist ears. The older Chaloner

had died of natural causes shortly after the Restoration, but there were still plenty of Cavaliers who would be delighted

to wreak revenge on a member of his family. It was unfortunate, but there was not much Chaloner could do about it, except

wait for the righteous anger to cool.

‘Look at his boots,’ he said shortly, becoming tired of May’s condescension. As they were obliged to work together, the man

could at least try to conceal his antagonism. Chaloner had managed it, and he expected the courtesy to be returned, so they

could concentrate on the task in hand. ‘How many vagrants do

you

know who can afford such good-quality footwear?’

May raised a laconic eyebrow. ‘I saw one with a fine lace waistcoat yesterday, which had clearly been filched from someone’s

washing line. Decent boots are more indicative of a fellow’s morals than his designs on the King’s blood.’

Chaloner was not so sure. ‘I am going to talk to him.’

May moved his coat to one side, revealing the dag – a heavy handgun – he had shoved into his belt. ‘Go on, then,’ he jeered.

‘And if you do learn he is a dangerous fanatic with a musket under his rags, rub your nose with your left hand. Then I shall

put a hole in him for you.’

Chaloner made his way towards the beggar, sweeping his brush back and forth to clear a path among the sodden litter of old

leaves and rubbish that carpeted the ground. May leaned against a wall, affecting a relaxed attitude by removing a pipe from

his pocket and tamping it with tobacco. The operation took both hands, which meant he would be unable to retrieve the gun

very fast in an emergency. It made Chaloner realise yet again what a dismal intelligence officer May was, and was surprised

Spymaster Williamson tolerated such flagrant ineptitude.

He moved closer to his quarry, keeping his head down to conceal his face, but at the same time watching the vagrant intently.

The man’s face was far too clean, and the stubble on his chin indicated that although he had not shaved that morning, he had

certainly done so the day before. He was about Chaloner’s own age – early thirties – and his demeanour was that of someone

in a state of high agitation. He lay on his side, in an attempt to look as though he was sleeping, but his knuckles were white

as he gripped the hem of his cloak, and his dark eyes were full of unease as he stared at the abbey’s door – through which

the King would emerge within the hour.