Stretching Anatomy-2nd Edition (17 page)

Read Stretching Anatomy-2nd Edition Online

Authors: Arnold Nelson,Jouko Kokkonen

Tags: #Science, #Life Sciences, #Human Anatomy & Physiology

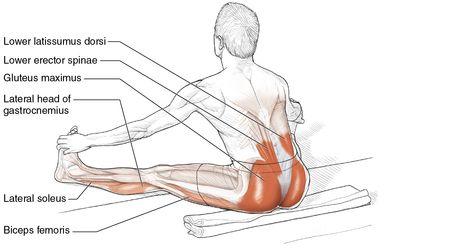

Keep both knees slightly bent while warming up. After the muscles are warmed up, you can move the knees into a straight position. To maximize the stretch, do not bend the knees, tilt the pelvis forward, or curve the back. Also, bend the trunk forward as a single unit, keeping it centered between the legs.

Changing the trunk position changes the nature of the stretch. For example, slowly moving the trunk in a position over the right knee puts more stretch emphasis on the right-side hip extensors, right lower-back muscles, and left-leg adductor muscles. Conversely, moving the trunk to a position over the left knee emphasizes the stretch in the left-side hip extensors, left lower-back muscles, and right-leg adductor muscles.

VARIATION

Seated Hip Adductor and Extensor Stretch With Toe Pull

By grasping the toes you can make this stretch more complex and thus increase its effectiveness by including additional muscles. You can stretch not only the calf, hamstrings, posterior hip, lower back, shoulder, and arm muscles but also the entire right and left sides of the body at the same time. The amount of stretch depends on how hard you pull the toes toward the knees and the tibia bone. Simply execute steps 1 to 3 of the Seated Hip Adductor and Hip Extensor Stretch, and then for step 4 simply grasp the toes of both feet and pull them toward your head.

Chapter 6

Knees and Thighs

The skeletal structure of the upper leg and knee is made up of the tibia and fibula (lower leg) and the femur (upper leg). These long bones in the lower and upper regions of the leg form the major lever system that allows the body to use the muscles of this region in all locomotive movements.

The knee joint is the only major joint between the bones of the lower and upper leg. It is classified as a hinge joint, and it allows only two major movements, flexion and extension. The range of motion, or the degree of freedom to move this joint, depends on both the bone structure and the flexibility of the muscle tissue, tendons, and ligaments that surround this joint. Typically, the knee joint is rather limited in movement compared with some other joints in the body, but the combination of the knee and the hip joint allows us to perform a variety of complicated movements and can enhance various sports and leisure activities. The more flexible these muscles are, the more freedom of movement possible.

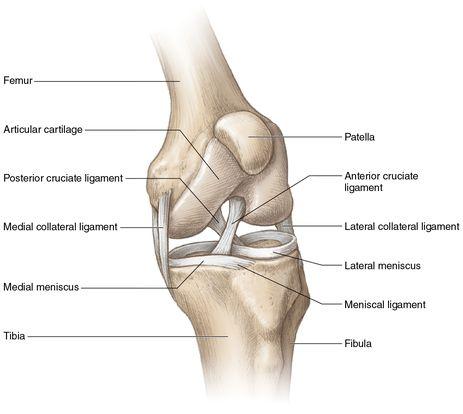

The knee is surrounded by a number of ligaments and tendons (

figure 6.1

) to bring more stability. In spite of these additional supportive structures, the knee is still quite vulnerable to a number of injuries. One of the most important ligaments around the knee is the patellar ligament. It extends from the patella to the upper front tibia. The tendons of the quadriceps muscles, located in the front thigh, blend with the patellar ligament, which attaches these muscles to the tibia. The medial collateral ligament supports the medial (inner) side of the knee, and the lateral (outer) side of the knee is supported by the lateral collateral ligament. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments help prevent anterior and posterior displacements of the femur on the tibia bone. These ligaments are located inside the knee and hold the tibia and femur bones together. The oblique popliteal and arcuate popliteal ligaments provide additional support to the lateral posterior (outer back) area of the knee.

In addition, the medial and lateral patellar retinacula also arise from the quadriceps tendon and contribute to anterior support of the knee. Finally, a meniscus sits on the plateau (top) of the tibia, which gives additional stability to the knee and cushions the bones during walking, running, and jumping. Wear and tear of these menisci bring pain most often to the medial (inner) side of the knee joint.

Figure 6.1

Knee ligaments and tissue.

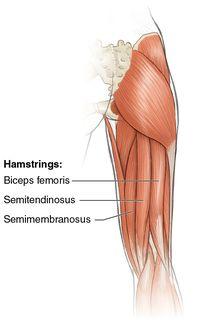

Most of the muscles that control the movements of the knee are found in the thigh. However a few calf muscles are also involved. Generally, the thigh muscles that move the knee are categorized into two groups. The four large anterior thigh muscles—rectus femoris, vastus intermedius, vastus lateralis, and vastus medialis—are collectively called the quadriceps muscles, and these are the major knee extensors. The large posterior thigh muscles—biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus—are collectively called the hamstring muscles, and these are the major knee flexors. The hamstrings are assisted in knee flexion by the gracilis and sartorius on the medial side of the thigh and the gastrocnemius, popliteus, and plantaris on the posterior side of the lower leg.

Flexion and extension are the two major movements of the knee. Most muscles in the body cross several joints, and thus many of these muscles are able to do several movements. Three of the quadriceps muscles, the vastus muscles, cross only one joint. This muscular arrangement allows these muscles to perform only knee extension. These three vastus muscles are strong extensors and sometimes may be sore and tight in front of the knee where the patella bone is located. Muscle tightness due to lack of stretching the quadriceps muscles is most often the cause of this problem. The knee extensors tend to exert less movement in walking, running, or jumping than the hamstring muscles. On the other hand, the hamstring muscles have two major movements—knee flexion and hip extension—and are active during any locomotive movement of the body. Thus, it appears that more total load is put on the hamstring muscles than on the quadriceps muscles. Because of this factor, the hamstring muscles tend to become more fatigued and sore than the quadriceps muscles during daily activities.

The muscles of the thigh that control the knee are important in all motor movements. Being much larger than the muscles of the calf and foot, the thigh muscles are better able to withstand muscular stress. Hence, muscular soreness occurs less often in these muscle groups. It is important, however, to have the right balance of strength and flexibility between the opposing muscle groups of the thigh. Most people have stronger but less flexible quadriceps muscles than hamstring muscles. People tend to stretch the hamstring muscles much more than the quadriceps muscles. This creates an imbalance between the two muscle groups. Chronic overstretching of the hamstrings without comparable stretching of the quadriceps can cause more harm than good. This is the reason hamstring muscles are sore more often than quadriceps muscles. Overstretching can also lead to chronic fatigue and a decrease in strength in the hamstring muscles. To correct this imbalance, you need to put more emphasis on quadriceps stretching and decrease the emphasis on hamstring stretching.

People often sit in one position for a long time, especially when in a car, sitting a desk, or an airplane. Thus, it is not surprising that after sitting for hours, people feel the need to get up and stretch. When people do stand after long periods of sitting, they typically find that their joints and muscles have become temporarily stiff. Most often you feel more stiffness in the knee joint, and getting up from a long sitting position could be a rather painful experience. Because of this, it is recommended to get up often during those long sitting hours and move around. Stretching these muscles is a natural remedy. Many people have found that stretching and moving the leg muscles provides relief from muscular and joint tension and pain. Since muscular soreness and tension are common in the thigh muscles, both temporary and lasting relief can be obtained from a regular daily stretching routine. This routine needs to be a consistent part of a fitness program.

The knee and thigh stretches in this book are grouped according to which muscle groups are being stretched. In addition, they are listed and described in order from the easiest to the most difficult. Stretches for the hamstrings are explained first, followed by stretches for the quadriceps, from easiest to hardest. Those who are new to a stretching program tend to be less flexible and should begin with the easiest level of stretches. Progression to a more difficult stretch in this program should be made when the participant feels confident she is able to advance to the next level. For detailed instructions, refer to the information on stretching programs in chapter 9.

It is also recommended that the stretches in this book be explored from different angles of pull. Slightly altering the position of the body parts, such as the hands or trunk, changes the pull of the muscle. This approach is the best way to discover where the tightness and soreness in the specific muscles are located. Exploring different angles while stretching will also bring more versatility to your stretching program.

All the instructions and illustrations are given for the right side of the body. Similar but opposite procedures are to be used for the left side. The stretches in this chapter are excellent overall stretches; however, not all of these stretches may be completely suited to each person’s needs. As a rule, to effectively stretch specific muscles, the stretch must involve one or more movements in the opposite direction of the desired muscle’s movements. For example, if you want to stretch the right biceps femoris, perform a movement that involves extension and external rotation of the right leg. When a muscle has a high level of stiffness, use fewer simultaneous opposite movements. For example, to stretch a very tight biceps femoris, start by doing only knee extension. As a muscle becomes loose, you can incorporate more simultaneous opposite movements.

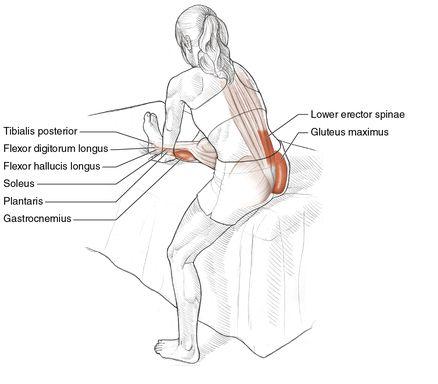

Beginner Seated Knee Flexor Stretch

Execution

- Sit on a couch, bed, or bench with the right leg extended on the surface.

- Rest the left foot on the floor, or let it hang down in a relaxed manner.

- Place the hands on the couch, bed, or bench next to the right thigh or knee.

- Bend at the waist and lower the head toward the right knee, keeping the back of the right knee comfortably on the couch, bed, or bench as much as possible.

- While bending forward, slide the hands toward the right foot, keeping them alongside the lower leg.

- Repeat this stretch for the opposite leg.