Stretching Anatomy-2nd Edition (14 page)

Read Stretching Anatomy-2nd Edition Online

Authors: Arnold Nelson,Jouko Kokkonen

Tags: #Science, #Life Sciences, #Human Anatomy & Physiology

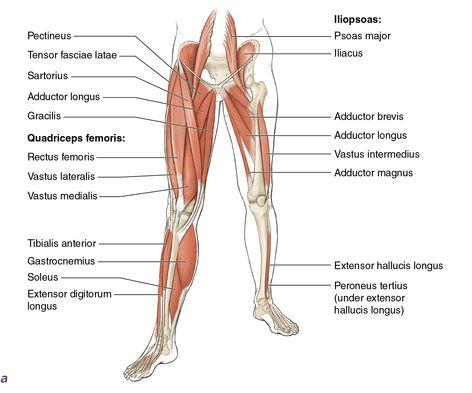

All but two of the muscles of the hip (

figure 5.1

) run between the pelvic bones and the thigh bone (femur). The two exceptions are the psoas major and piriformis, which run between the lower vertebral column and the femur. The muscles that move the hip joint are some of the largest muscles (adductor magnus and gluteus maximus) in the body as well as some of the smallest (gemellus superior and inferior). The anterior (front) muscles—the psoas major, iliacus, rectus femoris, and sartorius—flex the hip and are used during walking to swing the leg forward. The posterior (back) muscles—the gluteus maximus, biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus—provide the backward swing for walking. A group of large muscles (adductor brevis, adductor magnus, adductor longus, gracilis, and pectineus) on the medial (inside) thigh keep the legs centered under the body. A group of small muscles (gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, piriformis, gemellus superior, gemellus inferior, obturator internus, obturator externus, quadratus femoris, and tensor fasciae latae) on the lateral (outside) thigh splay the legs to the side. Another group that makes up more than 75 percent of the hip muscles is the external hip rotators, consisting of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, piriformis, gemellus superior, obturator internus, gemellus inferior, obturator externus, quadratus femoris, psoas major, iliacus, rectus femoris, sartorius, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, adductor longus, and pectineus.

Figure 5.1

Muscles of the lower extremities:

(a)

anterior;

(b)

posterior.

The range of motion, or the degree of freedom to move the hip, depends on several factors, including bony structure; muscle strength; stiffness of muscle tissue, tendons, and ligaments; and anatomical restrictions. For hip flexion, the range of motion is limited by hip flexor strength, stiffness of the hamstring muscles, and contact of the leg with the abdomen. Extension is influenced by hip extensor strength and the stiffness of both the hip flexors and the ligaments surrounding the ball-and-socket joint. Hip abduction is limited not only by the strength and stiffness of the adductors but also by the stiffness of the pubofemoral and iliofemoral ligaments and bony contact of the femoral neck and acetabular rim. On the other hand, hip adduction is restricted by the strength of the adductors and stiffness of the abductors as well as the stiffness of the iliofemoral and capitate ligaments. Besides muscle strength of the agonist muscles and stiffness of the antagonist muscles, internal rotation movement is restrained by the iliofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments, while external rotation is restrained by tension in the iliofemoral ligament.

Flexibility has more to do with overall body function than previously thought. For instance, diminished flexibility is one indicator of an aging body. Decreased physical activity also results in decreased flexibility. As people age and decrease their physical activity, they must keep stretching muscle groups in order to maintain mobility and range of motion in the joints. The hip region is located in the middle of the body, so problems in this area tend to radiate and affect many other parts of the body. You can reduce and even prevent many hip problems by paying more attention to strength and joint flexibility.

For instance, pain in the hip or buttocks area is often associated with poor hip flexibility. This is especially true after running or hiking along steep inclines or declines or even on slanted surfaces. Hip pain that occurs one or two days after activity is due to extensive use of the hip external rotator muscles and is caused by damage to both the muscle and the connective tissues in and around the muscle. Unfortunately, the hip external rotator muscles are small and usually weak and as such are not strengthened during typical strength-training activities. Therefore, stretching these muscles before and after the activity may help decrease this soreness and increase their strength. In addition, the hip external rotator muscles are the least-stretched muscles of the lower body, probably because these muscle groups are also the most difficult to stretch. We all tend to ignore those places in the body where we often find the most problems. On the bright side, it is easy to concentrate more on stretching those stiff and sore muscle groups.

The hip stretches in this book are grouped according to which muscle groups are being stretched. In addition, they are listed and described in order from the easiest to the most difficult. Stretches for the hip flexor muscles are explained first, followed by stretches for the hip extensors, hip adductors, and hip external rotators, in that order, from easiest to hardest in each category. Those who are new to a stretching program tend to be less flexible and should begin with the easiest level of stretches. Progression to a more difficult stretch in this program should be made when the participant feels confident he is able to advance to the next level. For detailed instructions, refer to the information on stretching programs in chapter 9.

It is also recommended that you explore the stretches in this book from different angles of pull. By slightly altering the position of the body parts, such as the hands or trunk, the pull of the muscle is changed. This approach is the best way to discover where the tightness and soreness in the specific muscles are located. Exploring different angles while stretching will also bring more versatility to your stretching program.

All the instructions and illustrations in this chapter are given for the right side of the body. Similar but opposite procedures are to be used for the left side of the body. The stretches in this chapter are excellent overall stretches; however, not all of these stretches may be completely suited to each person’s needs. As a rule, to effectively stretch specific muscles, the stretch must involve one or more movements in the opposite direction of the desired muscle’s movements. For example, if you want to stretch the right adductor magnus, perform a movement that involves extension, internal rotation, and abduction of the right leg. When a muscle has a high level of stiffness, use fewer simultaneous opposite movements. For example, to stretch a very tight adductor magnus, start by doing only hip abduction. As a muscle becomes loose, you can incorporate more simultaneous opposite movements.

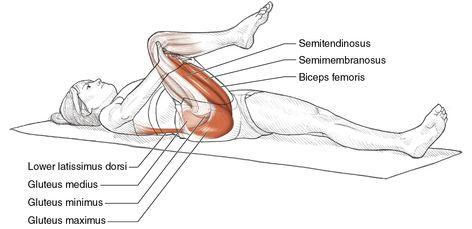

Hip and Back Extensor Stretch

Execution

- Lie on your back on a comfortable surface.

- Bend the right knee, and bring it toward the chest.

- While keeping the left leg flat, grasp the right knee with both hands, and pull it down toward the chest as far as possible.

- Repeat this stretch for the opposite leg.

Muscles Stretched

- Most-stretched muscles:

Right gluteus maximus, right erector spinae, right lower latissimus dorsi,

right semitendinosus, right semimembranosus, right biceps femoris - Less-stretched muscles:

Right gluteus medius, right gluteus minimus

Stretch Notes

This is another helpful and effective stretch for people who suffer from lower-back and pelvic or hip pain. Pain in the pelvic region is often a result of muscular soreness, and when muscles are sore, they often feel stiff as well. A person with this condition has a tendency to limit the range of motion of the affected muscles in order to avoid pain. Therefore, normal daily activities can be significantly affected depending on the severity of the pain. Rather than avoiding movement, a person suffering from this condition should specifically try to move and stretch the injured muscles. Performing the hip and back extensor stretch will provide increased flexibility and strength to these muscle groups, which in turn will help lessen the likelihood (or severity) of future injury.

For warm-up purposes, it is recommended that you use both legs simultaneously at first. Once warmed up, bring one knee up to the chest at a time. In addition, pulling the knee up toward the armpit will maximize the effectiveness of this stretch.

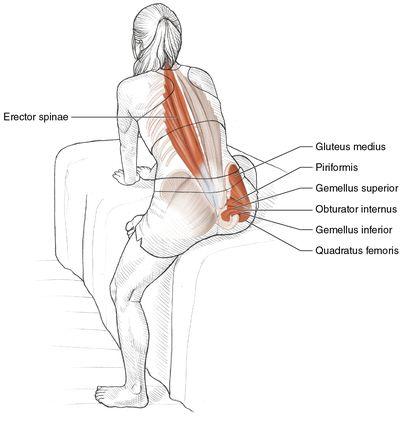

Beginner Seated Hip External Rotator Stretch

Execution

- Sit on a couch.

- Rotate the right leg at the hip, and pull the right foot in to rest flat against the left inner thigh, as close as possible to the pelvic area. The outside of the lower right leg should rest as flat as possible on the surface of the couch.

- Bend the trunk over toward the right (bent) knee as far as possible until you start to feel a slight stretch (light pain). Keep the left knee down, if possible, as you bend over.

- As you bend over, reach out with your arms over the right foot.

- Repeat this stretch for the opposite leg.

Muscles Stretched

- Most-stretched muscles on right side:

Gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, piriformis, gemellus superior, gemellus inferior, obturator externus, obturator internus, quadratus femoris - Most-stretched muscles on left side:

Erector spinae, lower latissimus dorsi