Stretching Anatomy-2nd Edition (7 page)

Read Stretching Anatomy-2nd Edition Online

Authors: Arnold Nelson,Jouko Kokkonen

Tags: #Science, #Life Sciences, #Human Anatomy & Physiology

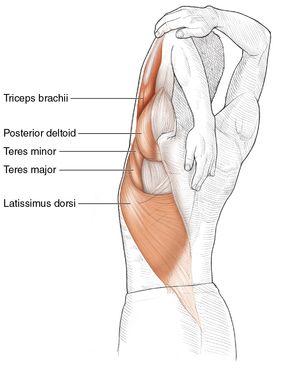

Grasping the inside of the doorjamb above head level reduces the stretch on the middle trapezius and allows a greater stretch of the posterior deltoid, latissimus dorsi, triceps brachii, teres major, and infraspinatus. Begin the stretch by squatting in front of a doorway, with the right shoulder in line with the left side of the doorjamb. Stick the right arm through the doorway, and, with the right hand, grab the inside of the doorjamb several inches above your head. Increase the stretch by lowering the buttocks toward the floor. Repeat again for the opposite side.

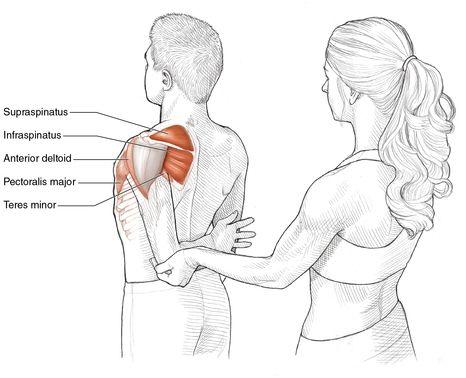

Assisted Shoulder Abductor Stretch

Safety tip Pull the elbow back gently.

Execution

- Stand upright with feet shoulder-width apart, with the toes pointing straight forward.

- Bring your left arm behind your back, with the elbow bent at 90 degrees.

- Have a partner stand behind you facing your back and grasp the left elbow.

- The partner gently pulls the elbow back and up toward the head, taking care not to pull suddenly or with great force.

- Repeat these steps for the opposite arm.

Muscles Stretched

- Most-stretched muscles:

Left supraspinatus, left infraspinatus - Less-stretched muscles:

Left anterior deltoid, left pectoralis major, left teres minor, left coracobrachialis

Stretch Notes

The supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles can become tight when a person does either repeated forward pushing actions, as when using a walk-behind lawn mower, or downward pulling actions, such as raising something off the ground using a block-and-tackle pulley system. The supraspinatus especially is always working during overhead movements and so can be easily strained when it fatigues. This stretch can also help relieve the pain associated with shoulder impingement, shoulder bursitis, rotator cuff tendinitis, and frozen shoulder.

If you have ever had someone twist your arm behind your back, you know that this movement can be very painful. The pain is magnified if these muscles are very tight. Therefore, the person assisting with this stretch needs to proceed slowly when pulling the arm up and back.

Chapter 3

Arms, Wrists, and Hands

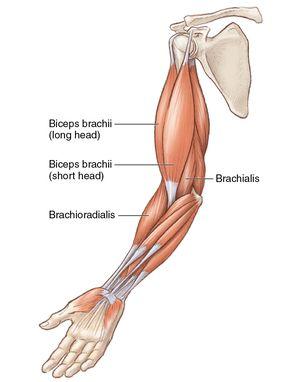

The major joint of the arm, the elbow, is made up of three bones. The humerus (upper arm) is located proximal to the body while the radius and ulna (forearm) lie distally. The elbow is a hinge and thus has only the capacity to either flex or extend. As a result, the muscles that flex the elbow (biceps brachii, brachialis, brachioradialis, pronator teres) are located anteriorly (on the front;

figure 3.1

), whereas the extensor muscles (anconeus, triceps brachii) are located posteriorly (on the back;

figure 3.2

).

The ligaments that help hold the three bones of the elbow joint in place are the joint capsule ligament, the radial collateral ligament, and the ulnar collateral ligament. The radius gets its name from its ability to roll over the ulna, and this ability allows the palm to face either forward (supinated) or backward (pronated). The head of the radius is connected to the ulna via the annular ligament. There are two muscles that supinate (biceps brachii and supinator) and two muscles that pronate (pronator teres and pronator quadratus). The pronator muscles are located so they can pull the distal radius toward the center of the body, and the supinator muscles are situated to pull the distal radius away from the body.

Figure 3.1

Biceps brachii, brachialis, and brachioradialis muscles.

Figure 3.2

Triceps brachii muscle.

The degree of available elbow flexion is limited primarily by the forearm contacting the anterior muscles of the upper arm, as well as the anterior proximal ends of the radius and ulna contacting the anterior distal end of the humerus. The tightness of the elbow extensors, however, along with the strength of the elbow flexors and the flexibility of the posterior portions of the capsular, radial collateral, and ulnar collateral ligaments also control the range of movement. These can be altered by stretching.

Although the major movements at the wrist are flexion and extension, the wrist is a gliding joint and not a true hinge joint. The gliding is possible because the wrist consists of the distal ends of the radius and ulna and the eight wrist, or carpal, bones. Thus, in addition to flexion and extension, the wrist can perform abduction (radial deviation) and adduction (ulnar deviation). The carpal bones are mostly held together by the various joint capsules, the palmar radiocarpal ligament, and the dorsal radiocarpal ligament. Interestingly, most of the muscles that control wrist, hand, and finger movements are located at or near the elbow. This results in the belly of the muscle lying near the elbow, with tendons crossing the wrist and attaching to the wrist bones (carpals), hand bones (metacarpals), and finger bones (phalanges). Having only tendons in the wrists and hands prevents the wrists and hands from getting too bulky from the increase in size that accompanies muscle strength.

Similar to the muscles that move the elbow, all the wrist flexors (flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, and palmaris longus) and most of the finger flexors (flexor digitorum profundus, flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor pollicis longus) are located in the anterior compartment of the forearm (

figure 3.3

a

). In contrast, all the wrist extensors (extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi ulnaris, extensor digitorum communis) and finger extensors (extensor digitorum communis, extensor digiti minimi, extensor indicis) are located in the posterior compartment of the forearm (

figure 3.3

b

). The muscles that run along the radius, which have radialis in their names, perform ulnar deviation, or wrist abduction. Those along the ulna, which have ulnaris in their names, perform radial deviation, or wrist adduction. Just before crossing the wrist, the tendons of these muscles are anchored firmly by thick tissue bands called the flexor retinaculum and extensor retinaculum. By passing under the retinaculum at the carpals (wrist bones), the tendons lie in a carpal tunnel. Since the tendons are crowded together, each tendon is surrounded by a slippery sheath to minimize friction.

Figure 3.3

Forearm muscles:

(a)

inside;

(b)

outside.

The movement ranges for wrist flexion, wrist extension, radial deviation, and ulnar deviation are all limited by the strength of the agonist muscles, flexibility of the antagonist muscles, tightness of the dorsal and palmar ligaments, and wrist impingement (ulnar deviation only). Interestingly, all of these, except wrist impingement, can be changed by doing stretching exercises.

Stretching the muscles that move the elbows and wrists is helpful in alleviating and sometimes preventing overuse injuries. Because it is more resistive to opposing movements, a tight muscle is easy to damage. When the wrist extensor muscles are tight, pain arises on the lateral (outer) side of the elbow. In sports, this pain is sometimes referred to as tennis elbow. Tight wrist flexor muscles, on the other hand, can cause pain on the opposite, or medial, side of the elbow. This pain is frequently called golfer’s elbow. Also, tightness in both the wrist extensors and flexors from either constant wrist hyperextension or flexion can lead to increased friction, inflammation, and overuse injuries such as carpal tunnel syndrome. People engaged in static or fine motor work such as keyboard use, computer mouse use, carpentry, or rock climbing are most likely to encounter this condition. To prevent and alleviate this condition, rehabilitation specialists encourage work breaks for stretching both the wrist flexors and extensors to help strengthen and loosen the muscles and tendons.

Many of the instructions and illustrations in this chapter are given for the left side of the body. Similar but opposite procedures would be used for the right side of the body. The stretches in this chapter are excellent overall stretches for all the arm muscles. However, some people may need to target a specific muscle or group and, hence, require stretches more suited to their needs. Specific muscle stretches require the involvement of one or more movements in the opposite direction of the desired muscle’s movements. For example, if you want to stretch the flexor carpi radialis, perform a movement that involves wrist extension and radial deviation. When a muscle has a high level of stiffness, however, you should use fewer simultaneous opposite movements. For example, to stretch a very tight flexor carpi radialis, start by doing only radial deviation. As a muscle becomes loose, you can then incorporate more simultaneous opposite movements.

Triceps Brachii Stretch

Execution

- Sit in a chair with a back or stand upright with the left arm flexed at the elbow.

- Raise the left arm until the elbow is next to the left ear and the left hand is near the right shoulder blade.

- Grasp the upper arm just below the left elbow with the right hand, and pull or push the left elbow behind the head and toward the floor.

- Repeat these steps for the opposite arm.